https://margaretannaalice.substack.com/p/remembering-gerard-van-der-leun-bon

I removed two of the guest posts, leaving the one regarding Thom Gunn

Remembering Gerard Van der Leun: Bon Voyage, — Mon Semblable, — Mon Frère!

by Margaret Anna Alice

May 29, 2023

“Sorry but I am dealing with some health issues that require I conserve my efforts. I do admire your work intensely and hope to help along to the extent of my ability

Best Christmas to you and God Bless.”

When I read those words from American Digest publisher Gerard Van der Leun on Christmas, I did not realize they would be the last ones he would write to me.

A month later, his girlfriend, a blogger known as The New Neo, wrote, “Gerard died peacefully in the small hours of the morning.”

That was on January 27, 2023—three days after she reported he’d gone into hospice care, itself less than a week after he’d been diagnosed with cancer.

And it wasn’t just any cancer. It was turbo cancer, according to Ann Barnhardt:

“Van der Leun of AmericanDigest.org – the bloggers’ blog – died yesterday from TurboCancer. He posted a month ago today, in fact through December 30th, in normality. He died yesterday of TurboCancer. He said publicly that he got the two first clot shots. I’ll leave it at that. But remember, one month ago today Gerard Van der Leun was doodling and toodling along like everything was fine, and today he is dead from cancer so aggressive that it took him from diagnosis to slab in DAYS. That’s what happens when you have no functioning immune system. For… whatever reason.”

One of my commenters alerted me to the gutting news on January 30. I sobbed as I read through the progression of posts documenting his hospitalization for COVID and back pain, his premature return home jotted down in his last post, the glimmer of hope that accompanied his transfer to rehab and negative COVID test, the rounds of testing—all concluding with the shattering diagnosis:

“This is the news no one wants to hear. It is my sad task to tell you that Gerard has cancer that has metastasized, and that treatment offers very little or nothing at this point. He has entered hospice care, his younger brother is with him, and other loved ones have gathered or are gathering to visit, as well as church members and pastor.”

I then revisited our correspondence, treasuring each poetic word—including the literal poem he wrote for me during his attempt to republish my Letter to the Menticided: A 12-Step Recovery Program (which he said reminded him of his New York Times Anonymous: The 12 Steps):

Márgarét, áre you gríeving

Over Substack code deceiving, ?

Code learning to write hells of spam, you

With seething cranium to care for, can you?

Ah! ás the brain grows older

It will shrink to insights colder

By and by, nor spare a “Why?”

While wading pools of Libdrool lies;

And yet you cringe and say “Why, why?”.

Now no matter, child, white shame:

Genetics’ spríngs sprout the same.

Nor clown had, no nor moron, expressed

What truth was heard clear, Holy Ghost guessed:

It ís the blight Libs was born for,

It is Progtards you mourn for.

In my reply to this gift, I asked:

“How did you know I was a Gerard Manley Hopkins fan? I included ‘Pied Beauty’ in my thank-you post to my readers last year.

“Are you named for him?”

He told me he was “named for my uncle who died in WWII.” I did not learn until later the layers of grief behind those words. But I will let Gerard tell that story.

His readers never saw my letter because, “Alas as I published this with the HTML something deep in the code replaced the font on my entire site”—an implosion he took in equanimous stride.

Not long after, he wrote these kind words to introduce my Corona Investigative Committee presentation notes:

“The savage and brilliant Margaret Anna Alice is asking why a lot in A Mostly Peaceful Depopulation. Here are some questions she poses concerning… TOTALITARIANISM”

When I thanked him for this surprise, he replied:

“I wish I could do more and shall. I do think you are admirable in your intensely researched essays. As well as being a formidable essayist.”

He then let me know, “I’m going to lift your entire linksoaked text on A Primer for the Propagandized,” which he soon did, describing it as “one of her shorter raids on the inarticulate.”

Gerard was one of the few publishers to pick up my third essay, Dr. Mengelfauci: Pinocchio, Puppeteer, or Both?, which followed on the heels of his publication of Letter to a Colluder, prefaced with “VERY IMPORTANT.”

When he wrote to let me know he had gifted me a complimentary subscription to his New American Digest (now defunct, sadly), he included this adapted literary reference some of you may recognize from The Waste Land—a line Eliot had leased from Baudelaire’s preface to Fleurs du Mal:

“Bon voyage mon semblable,-mon sœur.”

This spoke to our shared love of poetry. I once wrote him:

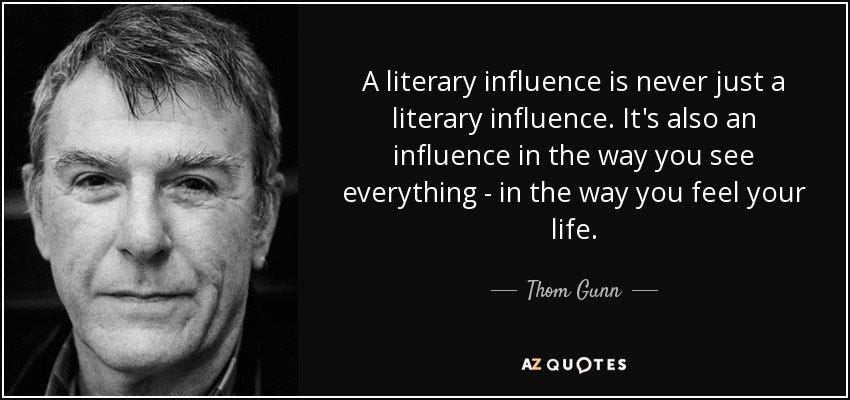

“I appreciated your Thom Gunn poem a while back as it reminded me of Oliver Sacks, one of my favorite and most-missed human beings and a dear friend of Thom’s. He discusses their friendship in his autobiography, On the Move.”

He informed me that Gunn was his teacher at Berkeley and gave me a peek at the memoir he wrote after Thom’s death, noting, “I’ve back posted it amidst the detritus of October and it should now be readable under this link.”

I replied:

“That portrait was poetry and brought tears to my eyes. It is a privilege to have met him through the words of two keen observers and fiery souls who loved him. I don’t think I knew that Oliver’s On the Move title came from a Thom Gunn poem, or if I did, I’d forgotten.… Thank you for sharing that ode to your beloved mentor.”

Since Gerard had surreptitiously published this memoir for me, it’s possible no one else has ever read it. It is my privilege to share it below sandwiched between the two pieces he asked Neo to publish upon his departure.

Originally posted on Memorial Day 2003, The Name in the Stone honors Gerard’s namesake, whose burial in the Atlantic at the age of twenty-two carved an indelible grief into his family tree.

As my husband read me this essay several days after Gerard’s death, I found myself weeping for both Gerards, for the innumerable soldiers whose lives were sacrificed in the name of ignoble lies, and for the family members whose hearts have forever been torn asunder—like Cindy Sheehan, whose son’s forty-fourth birthday would be today had Casey not been slaughtered at the age of twenty-four “in another US war for profit and global domination.”

While not a veteran, Gerard is a victim of the invisible war being waged against the public by philanthropaths, tyrants, and colluders—a war that is now known to have killed 13 million individual human beings to date.

And so, on this Memorial Day 2023, I commemorate Gerard and his fellow victims of democide as well as his uncle and every other soldier who has fallen on the battlefield throughout our blood-drenched history.

May the anguished lament of the third Gerard serve as their funeral rites.

‘No worst, there is none. Pitched past pitch of grief.’

by Gerard Manley Hopkins

No worst, there is none. Pitched past pitch of grief,

More pangs will, schooled at forepangs, wilder wring.

Comforter, where, where is your comforting?

Mary, mother of us, where is your relief?

My cries heave, herds-long; huddle in a main, a chief

Woe, wórld-sorrow; on an áge-old anvil wince and sing —

Then lull, then leave off. Fury had shrieked ‘No ling-

ering! Let me be fell: force I must be brief.’”

O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall

Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed. Hold them cheap

May who ne’er hung there. Nor does long our small

Durance deal with that steep or deep. Here! creep,

Wretch, under a comfort serves in a whirlwind: all

Life death does end and each day dies with sleep.

Margaret Anna Alice reposted both “Last Post” and “A Name On The Wall”, neither are repeated her. However, she also reposted the following

Thom Gunn [ 1929–2004 ]

by Gerard Van der Leun

Published at American Digest on October 1, 2022

Poet. Teacher. Mentor.

My Sad Captains

by Thom GunnOne by one they appear in

the darkness: a few friends, and

a few with historical

names. How late they start to shine!

but before they fade they stand

perfectly embodied, allthe past lapping them like a

cloak of chaos. They were men

who, I thought, lived only to

renew the wasteful force they

spent with each hot convulsion.

They remind me, distant now.True, they are not at rest yet,

but now they are indeed

apart, winnowed from failures,

they withdraw to an orbit

and turn with disinterested

hard energy, like the stars.

Thom (Thomson) William Gunn, poet, born August 29 1929; died April 25 2004….

No. Wait. Do not go.

[ 1929–2004 ] A bracket of dates and life moves forward. If we were like the beasts that we keep that would be the whole of it. But we move forward carrying the past with us. It is true that age and the ever-spiraling cascade of experience force us to discard large files of memory along the way, but if we are wise we keep those memories that sustain us and let the rest pass.

It is 1967 and I’m living with six other crazed young artists and hipsters in The Green House off Telegraph south of UC Berkeley.

The Green House was not a special place for the time. It was, in that time and in that place, ordinary. The most ordinary place in the world. If the Green House was neither real nor natural, it was fraught with a strange excitement, fecund with endless possibility. It was built of a metaphysic so loose that the most absurd accident could happen and it would only be a part of the Grand Design. It was a place where revelation and prophecy were daily events, the Second Coming scheduled for tomorrow after lunch, magic considered merely another, older branch of science, poetry an acceptable mode of speech, and caricature a widely appreciated attitude. As far as we know Rasputin, William Blake, St. Teresa, and Walt Whitman had never lived in The Green House, but they would have been welcome if they had wandered in.

1967: Because there’s a war on, I’m trying to stay in school. But because there’s a war on I’m trying to leave school. I’m also trying to become a poet for reasons that are now obscure other than it seemed like ‘a good idea at the time.’ Off the kitchen in The Green House is a small mud room with a screened window. Nasturtium and morning glories have twined across the screen and late into the night I sit scribbling and typing one attempt at poetry after another only to abandon most of them at first light. Dawn always reveals a small pool of crumpled sheets filled with errors, false starts, bad endings, failed metaphors, forced similies — all the detritus of …

Trying to use words, and every attempt

Is a wholly new start, and a different kind of failure

Because one has only learnt to get the better of words

For the thing one no longer has to say, or the way in which

One is no longer disposed to say it… —Eliot

It had not been my habit to throw anything away the previous year. Everything I wrote seemed to my young mind to be touched with light. Now I knew it had been garbage and had destroyed most of it. How did I know that? Because I had been fortunate enough to find myself in a poetry composition class taught by Thom Gunn.

1967: How many teachers do we have during our formal schooling? Two or three dozen? Fifty at most. How many do we remember? I remember three. A science teacher and a drama teacher in high school, and Gunn. I don’t remember Gunn because of how or what he taught, although that was part of it, I remember him because of who he was.

I remember the craggy, pitted face easily moved to laughter and a sensibility moved to kind despair when he was forced to experience a particularly bad line from one of his students. I remember that the class was formed of about 12 students and that on any given day at least ten were baked to a crisp. But that didn’t mean Gunn didn’t get our attention. How could he not? He was not only an elegant poet, an inheritor of the Tennysonian tradition in English poetry, but he was an elegant man.

I remember the craggy, pitted face easily moved to laughter and a sensibility moved to kind despair when he was forced to experience a particularly bad line from one of his students.

Gunn commuted in from his other life in San Francisco on a powerful motorcycle in leather and Levis. Then, before taking up his duties as a teacher, he’d change into what had to be bespoke English Suits and cowboy boots. It was a look that the students in his class—mired as we were in the hippy-regalia of the time—could not hope to emulate. But it was a look that spoke of refinement and manliness at the same time. It was not too much to say that we worshipped the man.

Unlike other ‘established poets’ I’ve run into here or there over the years, the hours spent in Gunn’s class were never about himself or his work. We were always asking him to read to us from his work, but he never did. What we were there to discuss, he always reminded us, was our work and the work it obviously needed.

And work we did. I’ve never pushed so hard on the craft as I did during that semester. Because that was what Gunn was about, the craft. Not The craft was not about nor was the craft interested in your feelings or your petty psychosis, not the confessional spew so popular at the time. Gunn had little patience for that even though he was invariably kind about pointing it out. What Gunn was interested in teaching was the one thing he knew he could teach: the craft, the rhetorical shape, and the internal beat, the way in which you could put words together to get a specific emotion back from the reader; the painting techniques of poetry; how to draw from life with words.

Most of the time, you failed at the craft since you’d been taught that craft was a foolish tool and that emotions were all that mattered. But slowly, with his remarks in class and his reactions to the work you submitted, you came to understand that you were actually improving. In hopes of improving more, you bought his books and internalized his poems. I have all his books now, the oldest of which I bought in 1967. I’ve read through and around them many times and they never fail to enhance and expand my life.

Gunn was kind and unsparing with his criticism, but he held back his praise. Somewhere I still have a sheet of paper with his polished handwriting telling me how vivid and effective he thought it was. I kept it pinned in front of wherever I was writing for years. It strikes me now that I’d really like to find it.

In time the class ended, summer came on, and I left the University and fled to Europe. Several years passed and I was working in an office south of Market Street in San Francisco. I was walking back to the job while waiting for a light, a motorcycle pulled up next to me at the curb. Black motorcycle. Helmeted rider. Bespoke English three-piece suit. Cowboy boots.

Recognizing me he lifted his visor and smiled that smile that made the day brighter. Held out his hand and we shook. The light changed and I said, just to be clever in the way that young men are, ‘Man, you gotta go,’ a phrase that opens one of his motorcyclist poems, “On the Move.” He laughed, nodded, hit the throttle, and faded away down the long boulevard.

Recognizing me he lifted his visor and smiled that smile that made the day brighter. Held out his hand and we shook. The light changed and I said, just to be clever in the way that young men are, ‘Man, you gotta go,’ a phrase that opens one of his motorcyclist poems, “On the Move.” He laughed, nodded, hit the throttle, and faded away down the long boulevard.

I never saw him again, but like all teachers and mentors that have touched our lives, he’s never really been absent. More than once over the years, I wanted to seek him out if only to thank him for what he’d added to my life. That always seemed beside the point. Now, to my regret, it is too late. Still, when I think of him or read his work as I will until my time arrives, I’ll always carry the memory of those classes and the long nights working amid the growing pile of crumpled paper on the floor in The Green House. In the end, that’s what the great teachers and poets leave us, the memories that live, the memories we choose to carry all our lives.

Addendum by MAA:

This comment by Jason Powers was so profound, I felt it earned its place as the closing words:

“Gerard, um, Jerry was a great writer. I read that short piece, and felt like a journey through time unfolded, and that is worth a lot in this time.

“My prayers, Jerry.

“You did earn the right to be called Gerard after all.

“Gerard will meet you soon.”