After that bit of detour a short way towards Denver from Junction, we return to our regularly scheduled journey to Latham.

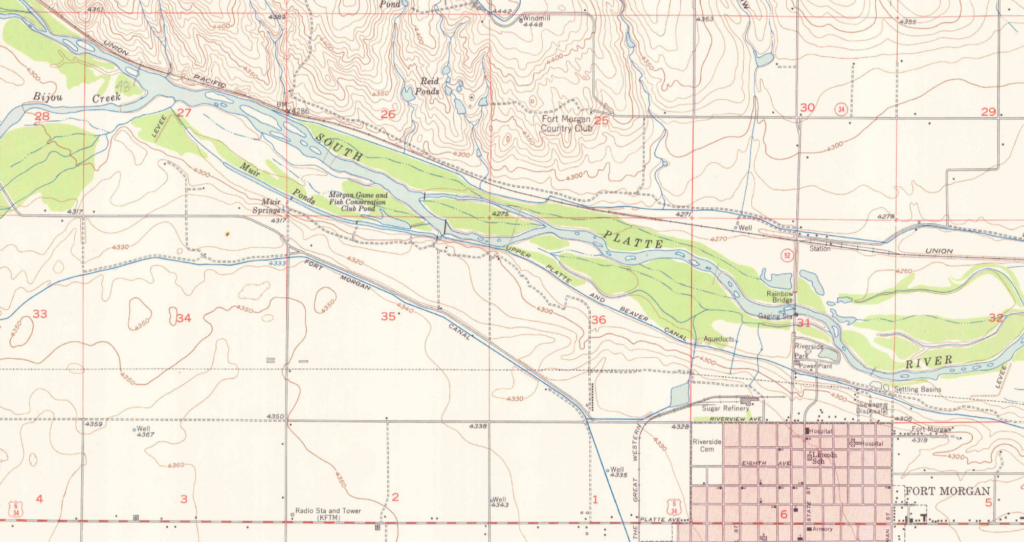

From Junction Station, our route takes us to what was the next station after Beaver Creek Station in the original days before the cut-off to Denver was built, the station at Bijou Creek.

After leaving the cut-off [near Fort Morgan], there is a long strip of heavy sand to cross, which extends to Bijou Creek, a small clear running stream, but which is more or less tinctured with alkali, and it was generally considered unsafe to allow the cattle to drink of it. This alkali consists of potash, soda, lime, magnesia, etc., the products of burnt grass and plants, which have been consumed by the fires that often sweep over these vast prairies.

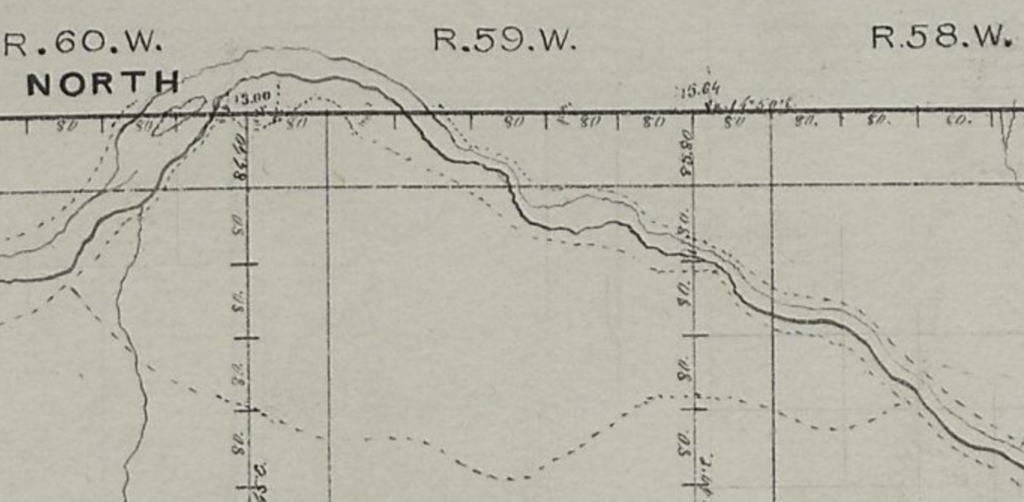

Even today, this stretch of what was one of the most difficult sections of the Overland Trail does not have a road following the stage route.

It is a notorious fact that many of the overland stage drivers and stock tenders, between three and four decades ago, were inhabited by a species of vermin known as pediculus vestimenti, but on the plains more vulgarly called “‘gray backs.” Some of the boys at times were fairly alive with them. It is not at all surprising, however, for they slept from year to year on ticks filled with hay — they called it “prairie feathers” — and their blankets were seldom washed from one year’s end to another. Some of the stage company’s employees didn’t indulge in a bath for several months at a time, especially during the winter season, when the weather was way down below the freezing-point and even the most plain and simple conveniences for a bath were greatly lacking.

During the hot weather of midsummer, when the vermin were rapidly multiplying, it was the custom of the boys at the station to take their underclothing and blankets in the morning, spread them out on the ant-hills, and get them late in the afternoon, minus the last grayback. This was the way they did their washing. They found it an excellent substitute for making the music of a John Chinaman on the wash-board. For a time, at least, after the “washing days,” they could enjoy some rest. But in a few weeks it would become necessary to repeat the operation of a general clean-out by placing their garments and blankets at the disposal of the ants. Nearly every stage-driver, stock tender, and bull-whacker along the South Platte infested with this kind of vermin, during the days of overland staging and freighting, well remembers the valuable services of these ants. Mammoth ant-hills, upward of a third of a century ago, were common in the South Platte valley in sight of the Rockies.

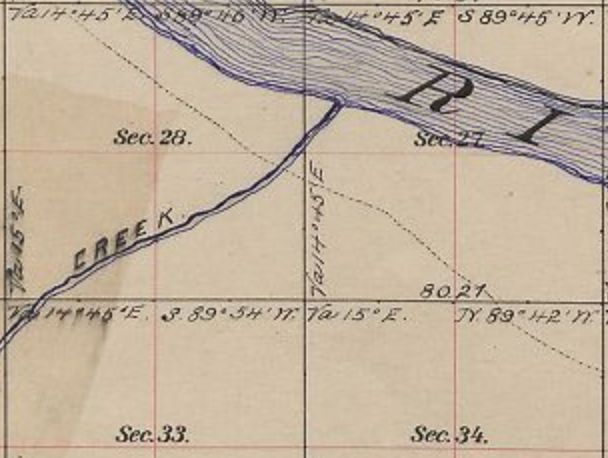

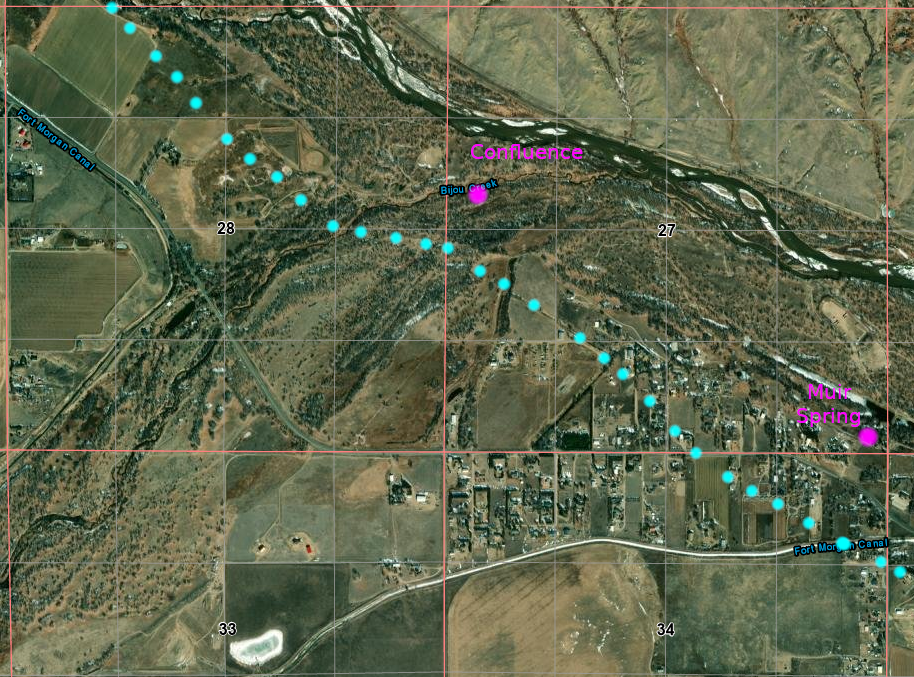

Bijou Creek

confluence w South Platte

4N58WS27NWSW

40.28540267305183, -103.86325537182204

Muir Springs 40.27662203737985, -103.84907444553562

at intersection S27/26/34/35 NW of Ft Morgan; SE of Bijou confluence

Joseph Bijeau dit Bissonet (d 1836) worked as a fur trapper for the Missouri Fur Company in 1806. In 1820, Bijeau was living with the Pawnee when he joined the Long expedition as a guide up the South Platte River to the Rocky Mountains.

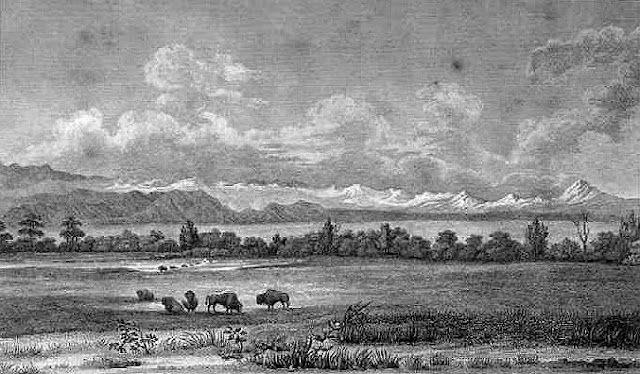

In June “…we discovered a blue strip, close in with the horizon to the west – which was by some pronounced to be no more than a cloud….when the atmosphere cleared, and we had a distinct view of the sumit [sic] of a range of mountains…”. Their first view of the mountains came just west of Fort Morgan near a creek later named Bijou by Major Long in honor of the expedition’s guide.

While going up the great Platte valley on a Concord four-horse stage-coach towards the grand old mountains at a gait of five or six miles an hour for twenty-four hours, the sight of over 100 miles along the snow-capped “back-bone of the continent,” the sun shining in dazzling splendor on the white mantle, it seemed as if we would never reach them.

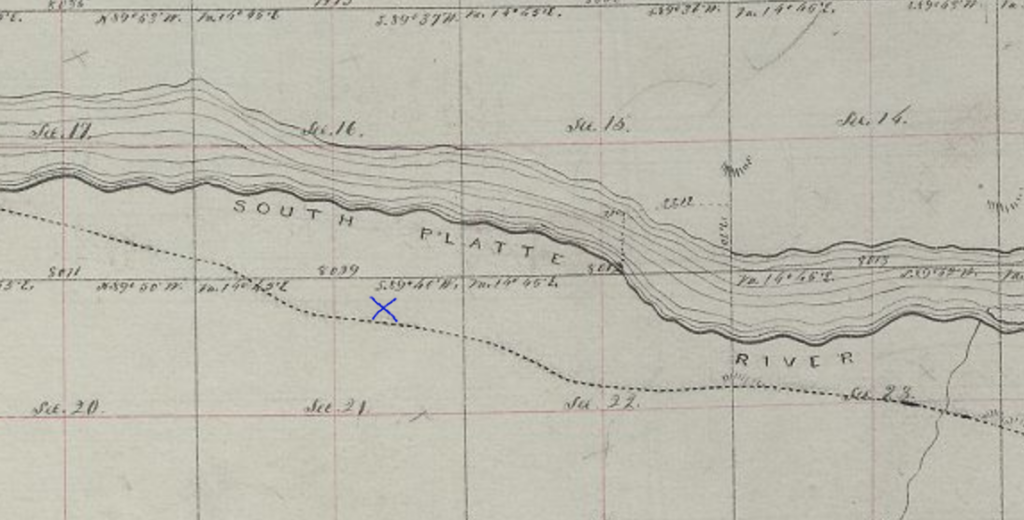

The Bijou Creek Station was located about three miles beyond Fort Morgan. Two routes headed west from there; neither appealing. One went up over a steep bluff, the other through sand deep enough that double teams were necessary to pull the wagons and stages.

The lower route more closely follows today’s I-76/US34

There is no modern road following the upper route

In October 1864, a change was made to the route. The South Platte segment of the route ended at Latham. The original trail, crossing to the north side of the river at the original site of Latham, then on to LaPorte and points west, was relegated to secondary status. The main line now detoured south to Denver from Latham – still a major station and supply depot, but an alternate 90 mile direct route to Denver from one of the “Junction” stations saved 3 days and the mileage from Bijou to Latham then the sixty miles to Denver from Latham. Leaving the South Platte at Bijou Station, its course to Denver over a toll-road was pretty much a straight shot of about ninety miles. Through Indian territory.

Bijou Station was one of several known as “Junction Station”.

Muir Springs was the source of fresh potable water for Bijou Station, the creek being too alkali to be safe or pleasurable to drink.

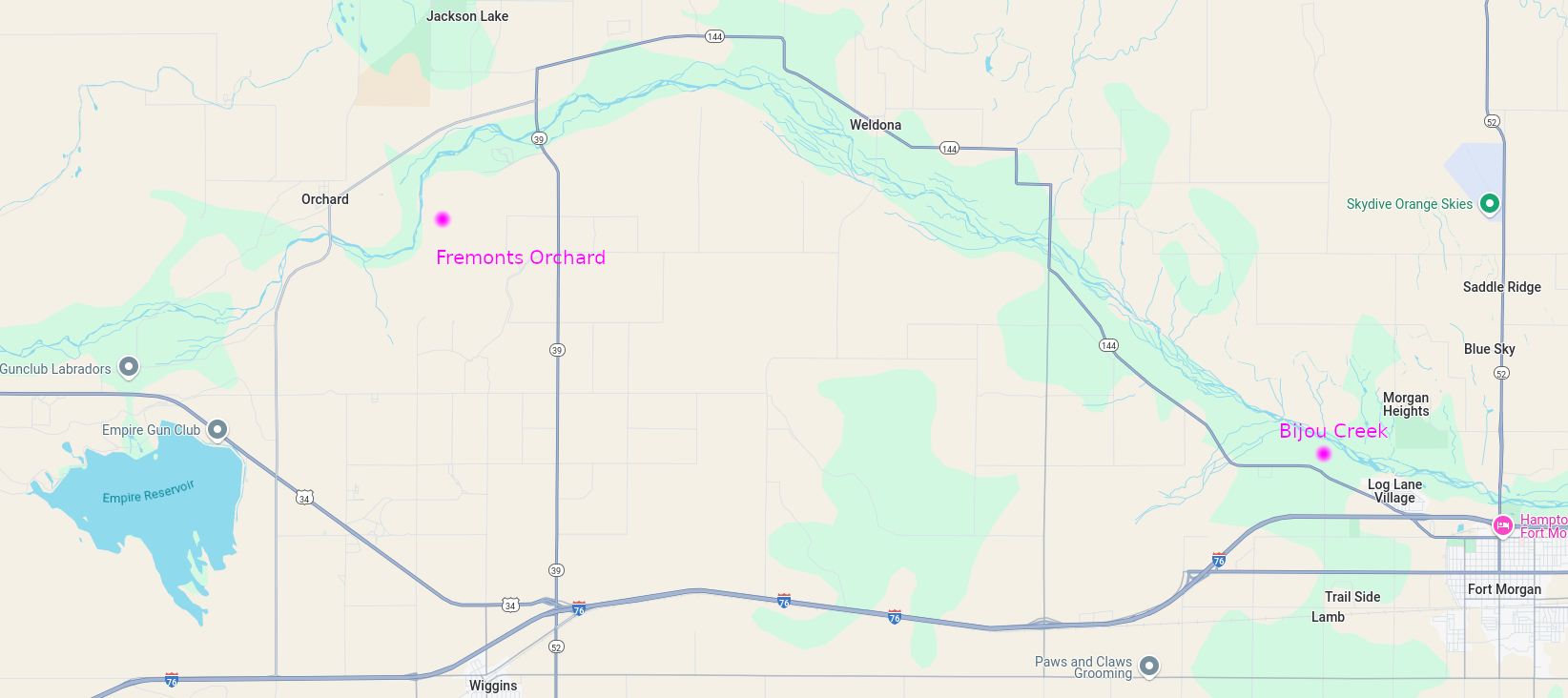

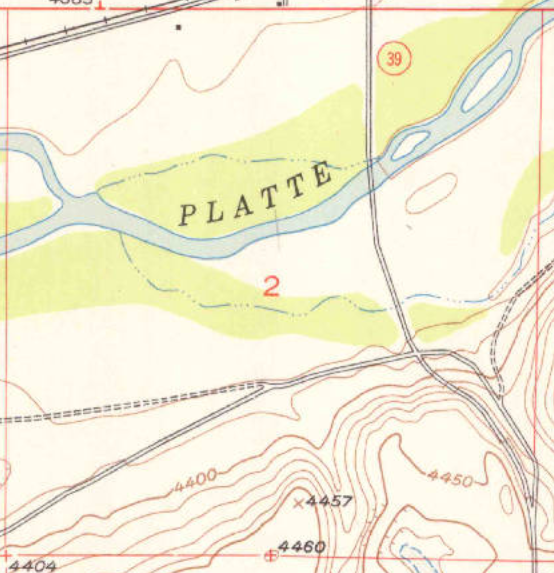

Even today, there is no road following along the length of the south bank of the South Platte River between Bijou Creek Station and a point between the Orchard and Eagle Nest Stations. Even what few ranch roads exist in the area – too small to be shown on this map – are not continuous and are broken by sand and irrigated fields.

While I-76 and US34 closely follow the southern alternate route cutting off the northern bow of the river, even now, Wiggins (1882; pop 1500) is the only town in that region of Colorado. Although a shorter alternate path, the majority of travellers on the Overland stayed with the river.

A glimpse of the river to the right

The next drive was likewise a long and tedious one — sixteen miles to Fremont’s Orchard. Much of this distance was through beds of sand, and there was not a drop of water nor a tree or a shrub for the entire distance. On this drive a “spike” team was used; i. e., five mules were hitched up, two on the wheel, two ahead of them, and the fifth hitched single in the lead. There was no going out of a walk on this drive, and no easy matter for the animals to haul a full load of passengers, with the express, mail and baggage that usually accompanied them.

Fremonts Orchard

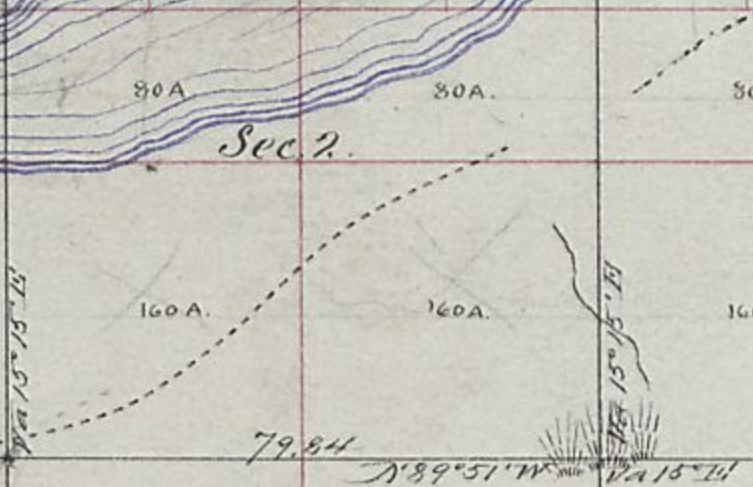

4N60WS02SWSW

40.33574805265367, -104.0723614517571

The next station west of Bijou Creek was Fremont’s Orchard, named for Captain John C. Fremont. This major stopping place and station was located approximately 18 miles from Junction Station and south of the South Platte River SW of modern-day Goodrich. A post office operated here in 1863/64 and again in 1874-1877.

In 1861 it was a logical site for a stage station [built 1862], an oasis after 16 barren and difficult miles from the previous stop. As with other stations along the Platte River Trail, Fremont’s Orchard became the center for early settlers in the region. It was a supply center, social center, a place for settlers to congregate to learn the latest news from “the states” or just to watch the hopeful emigrants go by. As was necessary for stage stations of the day, Fremont’s Orchard had thick sturdy walls, “a fortress” for settlers during the Indian scares – and there were many….

It was a real pleasure, after going so long on a walk through such a dreary stretch of sand, to reach the “Orchard.” There was quite a cluster of stunted cottonwood trees in the bottom that looked much like an old Eastern apple orchard; hence the name of the station. For years the trees furnished the station keepers and ranchmen in that vicinity all the fuel needed. A post-office was located here ; the first one west of Julesburg, more than 100 miles east. Eagle’s Nest was the next station, eleven miles west of the “Orchard.”

Fremont’s Orchard was not an orchard but simply a grove of cottonwood trees. Some emigrants noted that the large cottonwoods looked like apple trees, but another questioned the name, and wrote “…why it is called an orchard I cannot understand…” Later irrigation and development have increased the growth of mostly cottonwoods but reports from travellers of the day suggest such significant growth was rare. Fremont’s Orchard had long been a meeting and trading place along the South Platte and many early travellers camped there.

[June 1860]

14th.… Yesterday we drove 18 miles and passed Fremont Orchard & Fremont hills too, I guess, judging by some steep ones we came down. Came down one big hill into one of the most picturesque place one can imagine – the river filled with islands on one side and on the other were steep bluffs…. Fremont Orchard is a beautiful grove of trees that appear to stand in rows, it looks more like home to see the trees close by. Come over a very large sand hill and Mrs. Wimple and I went down the side to the bank and found a beautiful road and shade but we had just got to the teams again when we came to an alkali stream which we went around by a path on the mountain to where we camped for dinner on the Platte and a tribe of Cheyennes came along with their dogs & ponies, some of them have this year’s colts saddled for the papooses to ride. Some of the prettiest ponies for only ten dollars, but they won’t take any thing but silver dollars and we have nothing but half dollars. It is a very large tribe, we see one squaw 80 years old, she laughs at my bloomers. We afterward see her lugging a great bundle of wood as large as two men ought to take. See Indians all day. Find more alkali and some sand but we go the newest roads and so keep on the flats. Camped again on the flats and find a well already dug for our benefit. Campers keep coming down until 8 or 9 o’clock. There is a cloud coming up ugly and black that looks like rain. We get meat on the stove to boil. We don’t more than get into bed than the wind comes up and takes everything kiting. Among the rest of the Company’s tent [?] and they give a loud call for the hammer. Finally all gets still again and I go to sleep after concluding I will not blow away or it will not rain. I awake in the night dreaming everything horrid.

The trail at this point was a difficult one through heavy sands. Charles Clark described the journey from Bijou Creek to Fremont’s Orchard:

We frequently saw large surfaces thickly incrusted with it, and so thick was the deposit, that we could have scraped up bushels of it. It is more frequently observed after a heavy rain, it being dissolved, and then precipitated upon the surface of the ground. Passing on from this creek, we found near the river bank, a fine spring of water, issuing from a crevice on the wall rock, falling into a moss lined basin, and passing through a pebbly channel to the river – one of those crystal founts whose beauty is full as refreshing as its water.

After some miles of travel over the upland, we descended, and encamped for the night on a beautiful bottom, where we found excellent feed for our stock. After supper, and while many of us were seated within the tent, engaged at euchre, several of our number, who were without, discovered what they termed an ingis fatuus, or will-o’-the-wisp, dancing oer the bottom, near a line of marsh, and all were called out to look at it….

Just then, another one appeared, moving backwards and forwards, and apparently approaching us, and several of the party, with Fred at the head, proceeded after it. After some minutes, they returned and stated that they had succeeded in getting quite close to it, and one remarked that it was the “prettiest thing he ever saw, burning with a blue, flickering flame” -…[we] were about ready to start, when a smothered, tell-tale snicker, from one of the party, arrested our attention, and we decided to remain in status quo and await the denouement…. our will-o’-the-wisps were two lanterns, in the hands of men, who were out looking up their cattle….

On leaving here, we follow up the bottom, and soon rise a heavy hill, which leads us over a ridge for a distance of about two miles, when we descend a precipitous bank, and find ourselves in Fremont’s orchard, where there are many ancient looking cottonwoods, bearing a striking resemblance to so many old apple trees, which is the first timber that is met with after leaving O’Fallon’s bluff. The bluffs or sand hills that border this orchard on one side, are cut and divided into many channels, which wind and circle back for long distances, sometimes terminating abruptly, but oftener dividing into others, which, if followed, will sometimes lead to the summit of the hill, or back again to the bottom from whence we started.

In following them up, we notice on either side many niches and caves, together with isolated pillows and columns of sand; indeed, in many places it is like groping through the ruins of an ancient city. Here is an old cathedral front, with its gothic arches and columns, its pinnacles and spires, its ornamented niches and canopies, and large ramified windows; and there are numerous pedestals, towers, and fantastic figures, all of which are exceedingly curious, and well worthy of more than a passing notice. We continued our way through the orchard, which stretches out for a half mile or more; and at a distance of four miles, reached Fremont’s Hill…

A toll road was built between Bijou and Fremont’s Orchard in 1862 along the south side of the Platte, but even so, the road was still difficult to travel. A charter was issued a year later to improve the road, but the improvements did little to ease travel. The route through Fremont’s Orchard became less traveled in 1865 when the Overland Mail cut-off at Fort Morgan and went directly overland to Denver.

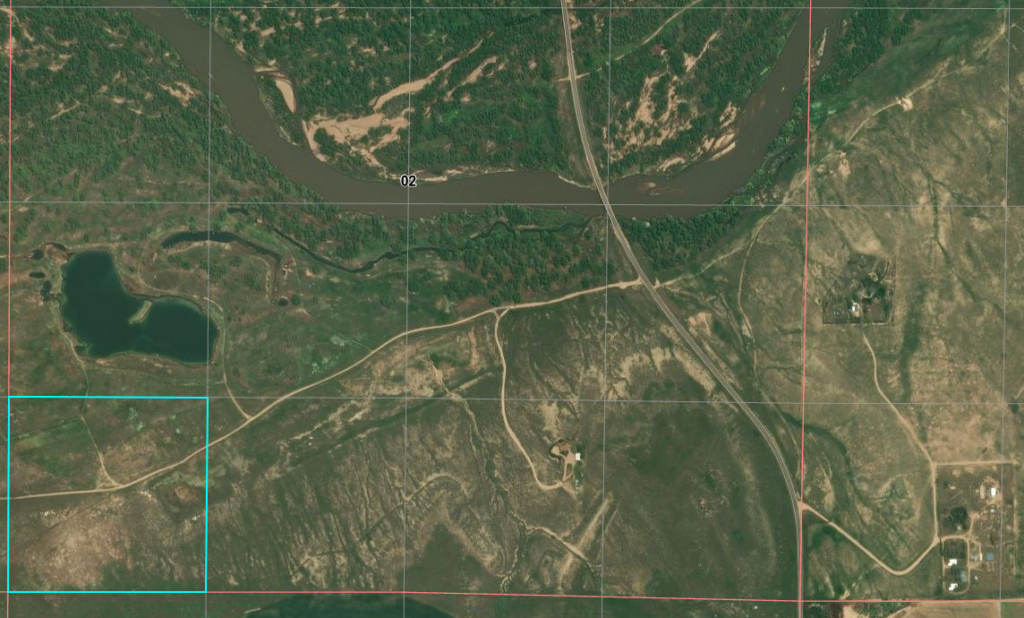

The rectangular area – possible site of Fremont Orchard structures

1864, Apr. 12

Lt. Clark Dunn, 1st Colorado Cavalry, and 40 men pursued some Cheyenne Indians into the bluffs north of Fremont’s Orchard to recover some mules and fought a short battle. This was the first serious fight with the Indians. A Cheyenne chief said that this was an unwarranted attack that started the war with the Plains Indians.

Battle at Fremont’s Orchard

On April 12, 1864, a company of about 20 soldiers based at Camp Sanborn (near Fremonts Orchard station) set out to find a group Cheyenne who reportedly stole stock from a local rancher:

…Ripley, a ranchman, living on the Bijon [sic] creek, near camp Sanborn, came into camp and informed Captain Sanborn, commanding, that his stock had all been stolen by the Indians, requesting assistance to recover it. Captain Sanborn ordered Lieutenant Clark Dunn, with a detachment of troops, to pursue the Indians and recover the stock; but if possible, to avoid a collision with them. Upon approaching the Indians, Lieutenant Dunn dismounted, walked forward alone about fifty paces from his command, and requested the Indians to return the stock, which Mr. Ripley had recognized as his; but the Indians treated him with contempt, and commenced firing upon him, which resulted in four of the troops being wounded and about fifteen Indians being killed and wounded, Lieutenant Dunn narrowly escaping with his life….

The Indians recounted a different version of events:

[E]arly in April, fourteen young men, all Dog Soldiers, left the camp on Beaver Creek and started north to take part in the expedition against the Crows. Before they reached the South Platte they found four stray mules on the prairie and drove them along with them. That same night a white man came into their camp and claimed the mules. The Indians who had found them told him that he could have them if he would give them a present to pay them for their trouble. The man went away to a camp of soldiers nearby and told the officer that a party of hostile Indians had driven off his animals…. According to the statements of Indians who were of the party the troops charged on them without any warning. Four men were shot by the Indians, one of whom they supposed to be an officer. Of the Indians Bear Man, Wolf Coming Out, and Mad Wolf were wounded. The soldiers retreated and the Indians, thoroughly frightened, gave up their expedition to the north and returned to the camp on Beaver Creek. They took with them the head of the officer, which they had cut off, and his jacket, field-glasses, and watch.

The military accounts paint the Cheyenne as the aggressors and in the Cheyenne accounts, the military charged without warning. It is possible that that the fault lay on both sides, the battle resulting from a grave misunderstanding; the military attempting to take weapons away from the Cheyenne may have been misinterpreted as a hostile act and the Cheyenne responded accordingly to protect their own safety. The discrepancies also include the injuries. The Cheyennes reported wounding a soldier and cutting off his head. The military records report four wounded soldiers (two mortally) who were taken back to Camp Sanborn and does not mention a soldier killed on the battlefield.

The Battle at Fremont’s Orchard signaled the start of the war with the Cheyenne. Over the coming months, Indians raids along the South Platte River and the military response escalated, culminating in the Sand Creek Massacre.

At a ranch out on the South Platte, the keepers had placed a board across .the top of two barrels to give the inside of the building something like the appearance of a frontier bar. At this place, it was said by a few of the stage-drivers and stock tenders that there was sold over this ” bar ” a decoction of some of the vilest stuff under the name of “old Bourbon whisky ” that ever irrigated the throat of the worst old toper.

Eagles Nest

4N62W

40.30249677011092, -104.32635193640856

I find virtually nothing about this station – or even about this now-resort with the same name and close to the station location based on Overland mileage. It is listed as a ranch on the oldest “new” maps; it appears to be a resort on the latest maps. It appears to be not open for business nor presenting anything more than a name.

Similar to South Platte Station in the sense of obscurity. Apparently, a very small station, consisting of only a barn, corral and house. It is the last station before Latham, a major station, and the next after Fremonts Orchard, a place of notable relief, which may explain the obscurity of information – other than casual mentions in writings of the time.

The location shown here is based on the location of Eagles Nest Ranch. This location fits the mileage logs of the time given variations in the road over the years.

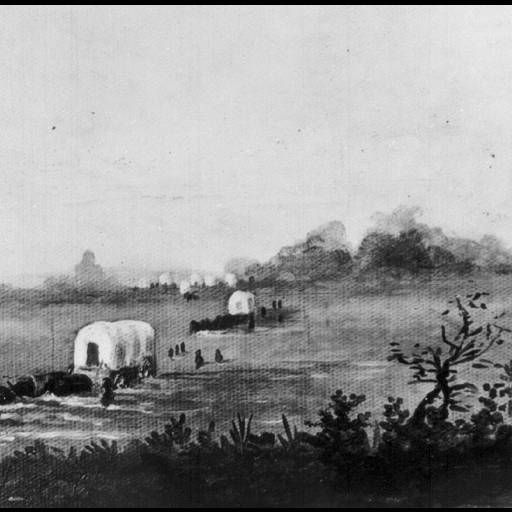

On the plains one would experience all kinds of weather. Sometimes, while making a trip, after a long dry spell, accompanied by a strong wind, the dust encountered was almost intolerable. Where there was so much travel, in hot weather, there were usually immense quantities of dust. Along the Platte river, where there was such enormous traffic — hundreds of wagons, some drawn by six yoke of cattle, passing over the road daily — it was worse than on any other part of the route. Portions of the road at times were like ash-heaps, because much of the way the soil was very sandy.

When the road was lined with mule and ox trains moving east and west, as a matter of course the animals were constantly stirring up the dust, which in places frequently was from three to six inches deep. With a strong wind blowing clouds of dust in one’s face — sometimes constantly for two or three days — the result can better be imagined than described.

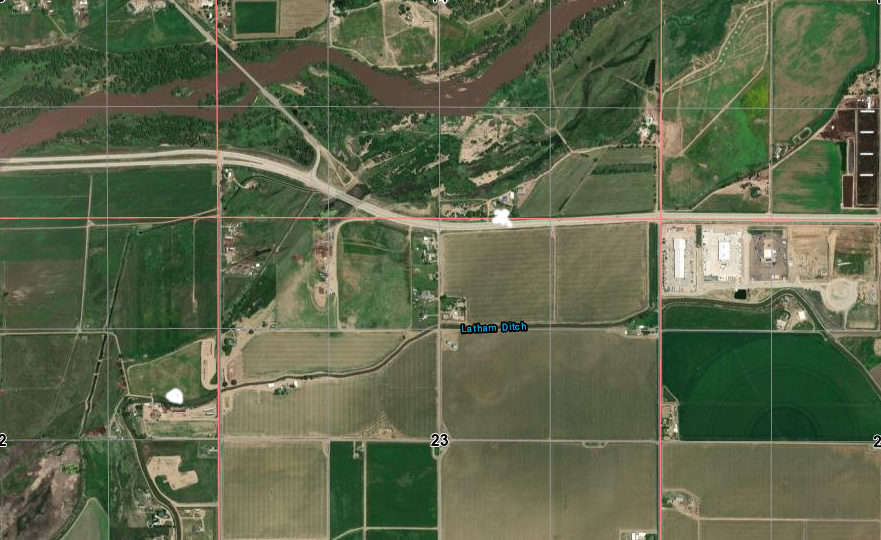

The diagonal trace on the modern view is US34

Latham

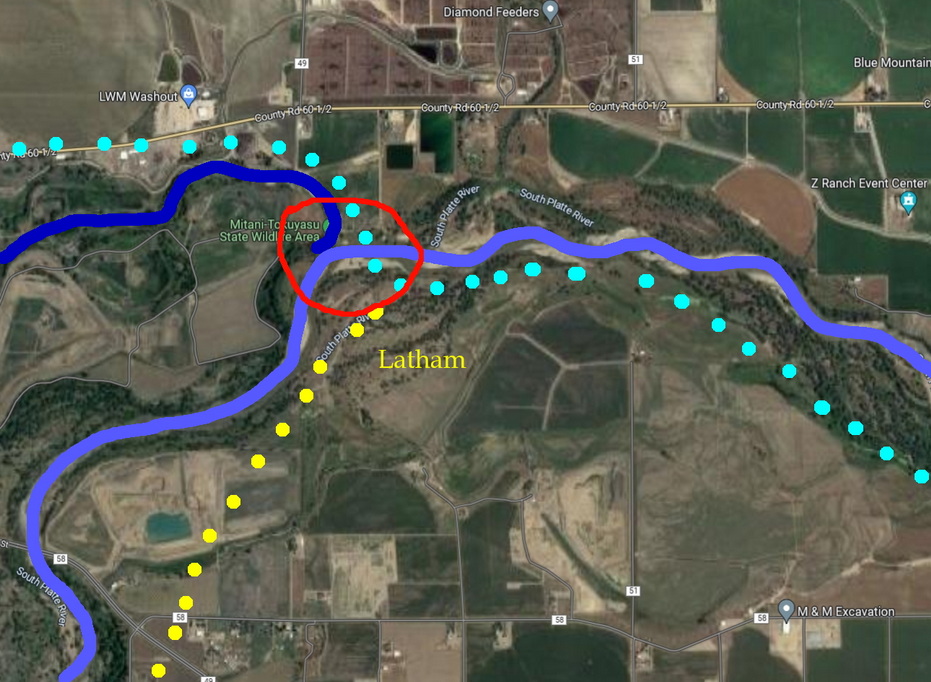

40.41937698438087, -104.59741610352786 south side at confluence – 1st Latham

40.42237220662745, -104.59953840459076 (2nd crossing)

looking at map shows river crossing 5N65WS14SW station likely S23NE

40.390399386458874, -104.62352690811124 2nd (main) Latham

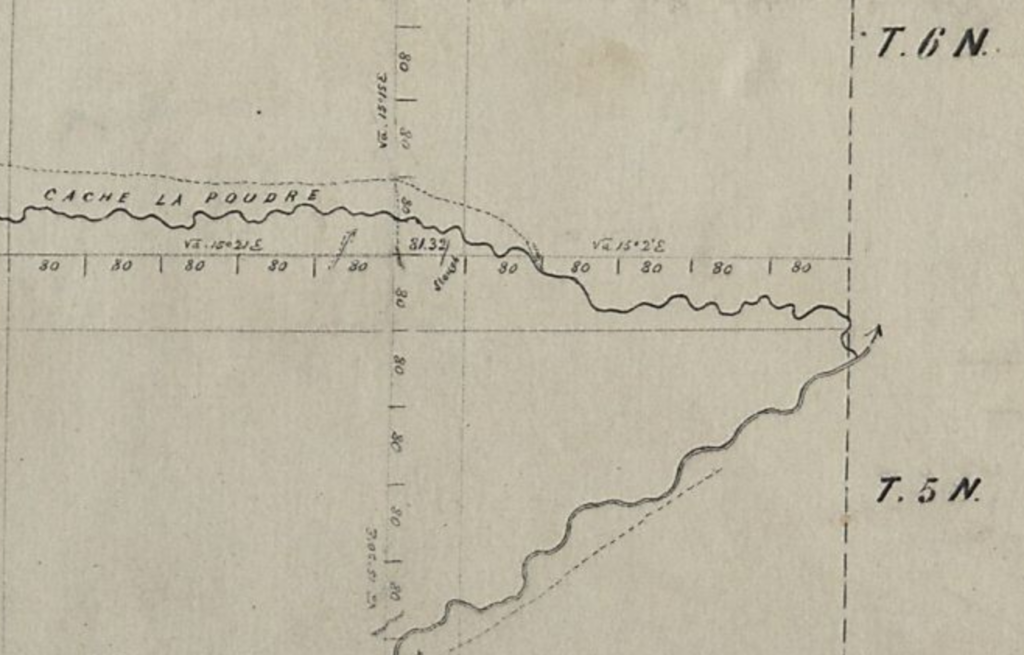

Latham Station – the first of two sites – was the western terminus of the South Platte River route of the Overland Stage. First established near the confluence of the Cache la Poudre River, this is where travellers crossed to the north side of both rivers and travelled onward along the la Poudre to LaPorte.

The station was moved upstream after the flooding of 1864. The town of Greeley did not exist at that time and is built on the land between the two rivers. The la Poudre now flows along the northern edge of the city.

This is the location of the confluence today from the north bank. Old Latham would have been on the south side of the river to the left. After the river flooded and damaged the station, it was moved about 1 mile upstream and to higher ground.

5N64WS06SWSW

40.4221881270978, -104.59971307954274

It is speculated Latham Station was here on the south side of the river.

Remote as this image seems, this area is highly developed

many things – including the river – have likely shifted around with time

Route from Latham to la Poudre not shown

Unfortunately, the confluence – and likely station location – are on the edge of township and range

Latham was the starting point of the southbound stagecoach line to Denver, the northeastern stagecoach route along the South Platte River Trail, and the northwest turning point along the Cherokee Trail toward the Overland Trail through Wyoming to Salt Lake and beyond. As such, it was one of the most important of home stations. Latham was never attacked by Indians, but Mother Nature did the original town in during the floods of 1864.

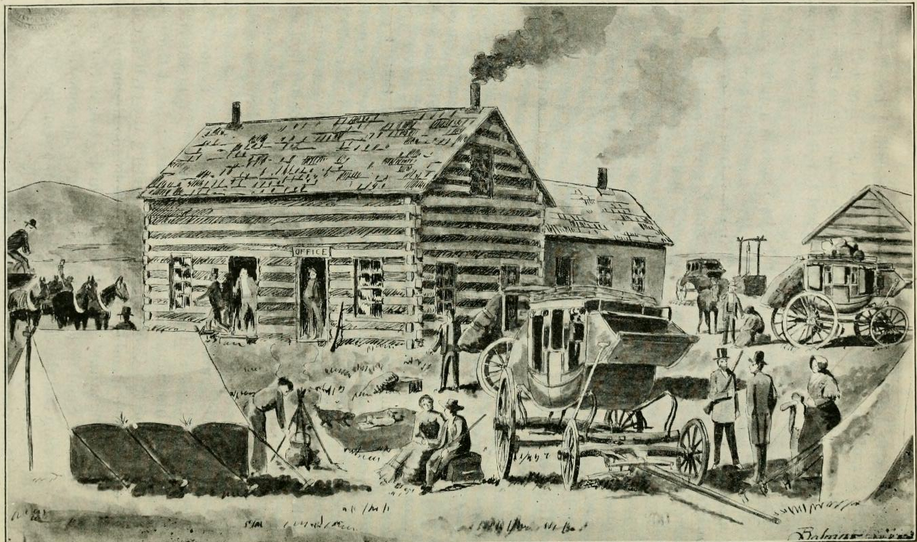

Latham was a major stop. A rest from travel for both people and horses. Latham was the “Flying J” of its time – offering a variety of services including food, water, a place to wash, outhouses, animal feed, a bed, tobacco, a blacksmith, timetables, mail, stamps, rope, ammunition, medical assistance, newspapers, leather repairs, whiskey, weather reports, conversation.

Latham (first known as “Cherokee City”) was the next station, and an important one it was, too. The distance was a little over 592 miles west of Atchison, and sixty miles northeast of Denver. Here was the junction of the stage lines for Denver and California, after the old Julesburg crossing was abandoned, in the fall of 1863, and here it was that the coaches for Salt Lake and points beyond forded the South Platte

And now – not even a hint of what existed at either location except an obscure historical marker in someone’s front yard (and apparently, since removed).

after flooding, the station was moved about 1 mile to the white dot

The trees in back line the river

For hundreds of miles down the Platte east of Latham the Indians were bold and defiant, and apparently ran matters to suit themselves. They had in many instances run off the stage stock, burned the company’s buildings, destroyed hay and supplies, and a number of emigrants had been horribly murdered, scalped, and left by the wayside.

Precaution was taken by Mr. Mcllvain, the station keeper, to lay in an ample supply of flour, ham, bacon, potatoes, dried fruit, sugar, coffee and other eatables at the beginning of the troubles, and, by his foresight, he saved for himself several hundred dollars, and his guests were well cared for. Latham was the best eating-house between Fort Kearney and Salt Lake City.

As mentioned earlier, Latham was built in 1862 as the last station on the South Platte route near the mouth of the Cache la Poudre River. It was built on a flood plain – convenient to the crossing – but heavy flooding destroyed much of the town in 1864. The station was too important to abandon; it was moved upriver a mile or so to higher ground.

As a junction point for both the trail to Denver and the river crossing for points west, it became the most important and busiest facility on the Overland Trail. The station was a long, low, one and a half story log structure. An addition held a dining room, kitchen, bedroom, storehouse and the telegraph office. It was located near and south of the present US34BR bridge into Greeley.

Being a major junction point, traffic could be heavy from three directions. As the major station, it provided storage for company supplies – grain, soap, candles, tack, etc – for all three Overland divisions. Heavy traffic could see as many as 40 passengers at one time – 5 or 6 stages worth. Mail was collected, stored, and sorted here for transport to the next destination.

Unlike now, the station was in a desolate location; the nearest neighbor was a rancher down the road towards Denver.

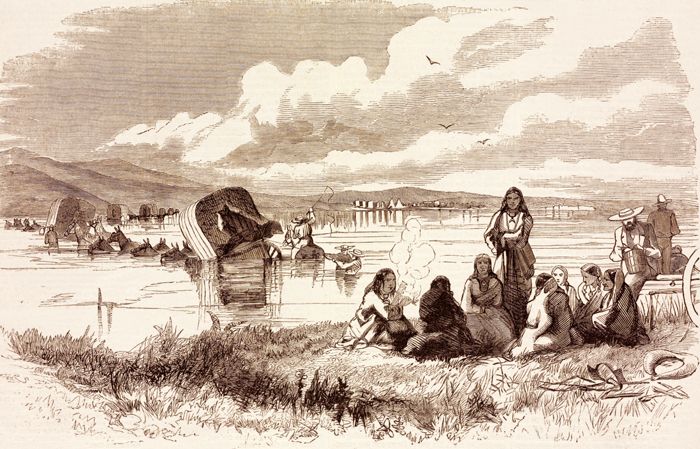

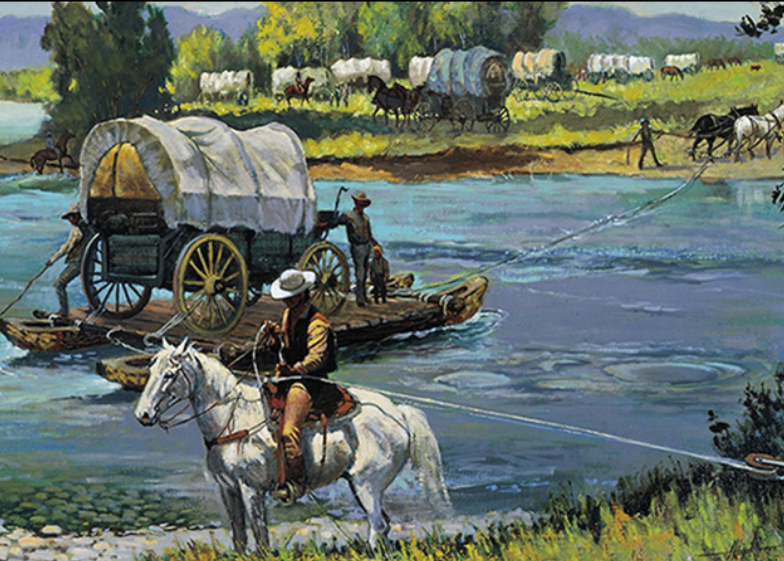

The road south to Denver would follow a trail continuing along the east (south) bank of the South Platte. For those headed west, the trail crossed the South Platte here, at times, over a mile wide. Crossing in late spring could be troublesome when water ran high due to the spring melt. A ferry was established and charged $1.00 per wagon, but the wagons had to be disassembled first.

The next stage station west was LaPorte, a trip of some 35 miles, with one small station in between (maybe – as it is reported) of questionable location; one being claimed in what is now the town of Windsor, another more likely at a ranch closer to what is now Ft Collins.

Latham was never attacked by Indians, although reports of nearby problems kept the station staff on edge.

From Frank Root’s reminiscences (1901):

The original county-seat of Weld county was located at old St. Vrain. Later it was given a temporary abode at the houses of two neighboring ranchmen. Next it went to Latham, four or five miles from Greeley and three miles due east from Evans, and remained for several years, that town and Greeley being about four miles apart. There was a lively competition between the two latter towns, and for several years there was a bitter county-seat fight, first one getting it and then the other. The election in 1877 settled the contest, when Greeley won the prize, and ever since it has remained there. Greeley is a temperance town, never having had a saloon, while Evans is a licensed-liquor town.

The stage station was the only house there. It was a substantially built one-and-one-half-story log structure, fronting south. There was a large one-story, rough-board addition built on the north side, fronting both east and west, in which were a large dining-room, kitchen bedroom, and a storehouse. Its location was important. It was the junction of the branch stage line to Denver, and stages made close connections east and also with the main line to Salt Lake and California. Besides, it was a storehouse for supplies for three divisions, and this made it the most important way station on the overland route between Atchison and Placerville.

Prominent as Latham was in 1864, the name of it at this late day is seldom mentioned. There are scores of people born in Weld county and still living there who probably have never heard of this station which was wiped out five years before the capital of the county was dreamed of. There are hundreds of people now residing in the vicinity who could tell little or nothing of the history of the old station as it was in the palmy days of overland staging.

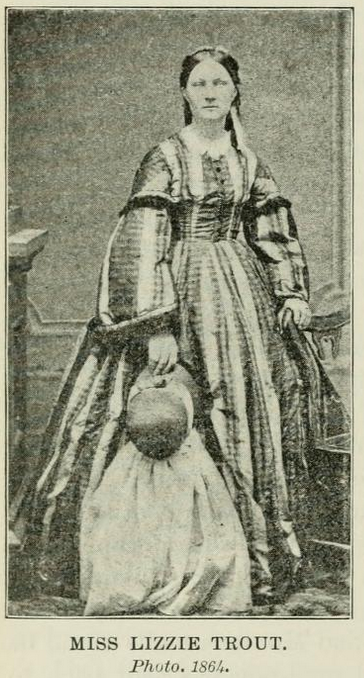

The eating station was kept by Mr. W. S. McIlvain, a genial warm-hearted man, who was also the stage company’s agent. With the aid of his estimable wife, assisted by Miss Lizzie Trout, whose services had been secured at ten dollars a week as cook, he gained the reputation of keeping one of the best eating-houses on the entire line of nearly 2000 miles.

He spared no pains to have his table supplied with the best to be found in the Denver market. He bought the very best coffee, paying one dollar per pound for it. He also bought fresh butter and eggs from the ranchmen in the vicinity, often paying $1.25 per pound for the former and $1.50 per dozen for the latter. The price of nearly everything else used on the table was in proportion.

Except at the hours when the stages arrived and departed each day, the station at Latham was a desolate and lonesome place. The nearest neighbor was a ranchman named Westlake, nearly three-quarters of a mile southwest toward Denver. He was on the main road and kept a gin-mill and a few goods for sale to the ranchmen in the neighborhood. He made the most of his money selling “cold pizen” to the numerous freighters and ox drivers passing up and down the Platte.

Lanham Station cook

While it was against the rules of the stage authorities to allow any liquor about the station, the thirsty drivers and stock tenders knew they could always get a drink or a private bottle filled at Westlake’s. They had often heard the pioneer ranchman and keeper of the place say that he might run short on the “luxuries of life,” but the “necessaries” he would always keep in stock.

In a radius of ten miles from Latham there were less than that number of ranchmen; but, in a number of respects, the station was looked upon as a very important point. It was a storehouse for grain, soap, candles and “dope” for the stage company. There it was that the stage teams forded the South Platte on their way to and from Salt Lake and California, and there it was that the mail-pouches for the Pacific slope were taken off the stages, immediately on their arrival, and examined, reloaded and rechecked for their destination.

It was only a few miles from Latham to where is now the county-seat of Weld county, the wide-awake city of Greeley. But at that early day –1864–Greeley was not dreamed of. The first building in that town–named for the New York Tribune founder–was erected in the spring of 1870.

There had been little difficulty in the stage teams fording the river at Latham until the great flood in Cherry Creek, which occurred on the night of the 20th of May, 1864. At that time the flood, which came with hardly any warning, swept away, almost in an instant, the Rocky Mountain News office and a score or more of other buildings in Denver, resulting in the destruction of a large amount of property and considerable loss of life. This flood caused the Platte to rise at Latham so it was nearly bank full on the afternoon of the 21st. The next morning it was several feet higher, and out of its banks.

And here we leave the South Platte and head up along the Cache la Poudre …

Next: Latham to LaPorte