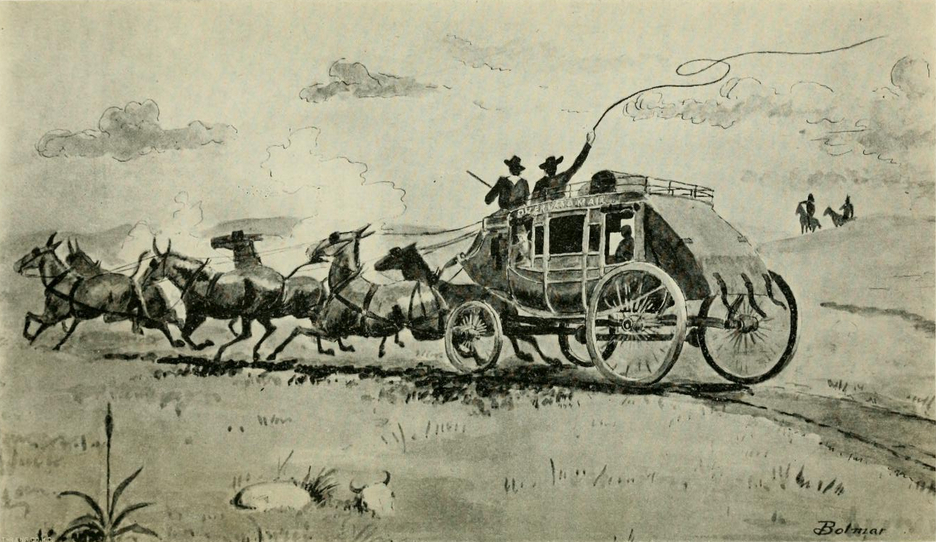

The settlement of Utah by the Mormons in 1847 and the discovery of gold in California in 1848 led to a need for a mail route from the “end of civilization” at St Joseph, Missouri to the new population settlements at Salt Lake City and Sacramento. Mail service from San Antonio to San Diego had been started in 1857 by a private company; later that year, Congress authorized a government contract for US Mail delivery from St Louis to San Francisco. John Butterfield was awarded the contract in 1858 with a route running from Memphis to Ft Smith, Arkansas, through El Paso, along the southern border (though the lands of the Gadsden Purchase) through Tucson, and on to Los Angeles up the Central Valley to San Francisco. The route was selected as avoiding snow and mountains. The route was judged an excellent road; the one-way journey took almost 2 months.

Attempting to provide faster “express” service, a shorter route using men on horseback rather than stage coaches or wagons was started in 1860. Cutting straight across the central west, the Pony Express could deliver mail in 10 days between St Joseph and Sacramento but the operation was not awarded an exclusive delivery contract. In spite of high delivery charges and subsidies, the Pony Express was not profitable and the competition of the transcontinental telegraph in 1861 caused the demise of the venture.

Meanwhile, after the war back east started, the route had to be moved north and Ben Holladay was awarded the mail contract between Atchison and Salt Lake after purchasing the assets of the Pony Express holding company. He named the new company The Overland Mail Company. The post office designated the route: “Central Overland California Route.”

A large number of employees was necessary for such an operation as the Overland Stage. Aside from Ben Holladay, the main company officials were Bela Hughes who served as the general counsel; David Street as Paymaster; and Robert Pease as the trustee.

The operation was divided into three major divisions; from Atchison to Latham (later Denver*) was the eastern division; Latham to Salt Lake was the mountain division; and the western division covered Salt Lake to Placerville. A superintendent was placed in charge of each division, each again divided again into three subdivisions being of about two hundred miles in length. A division agent having considerable authority was in charge of each minor division; he being in charge of all company property within his territory.

*Denver itself was a small mining camp on the South Platte River at Cherry Creek in the earliest gold mining days of 1858/59 near where today’s Speer Blvd crosses I-25. Several other settlements in the area were larger – notably Auraria. Golden – about 15 miles west – was the capital of the Jefferson Territory, then the Colorado Territory until 1867 when the capital was moved to Denver. Denver is now a major metropolitan city; even the location of Latham is now relatively uncertain.

The division agent was usually an experienced stage man, often having risen from the rank of driver. The agent was responsible for the purchase of all the grain, hay and supplies for his division, he hired the station-keepers, drivers, blacksmiths, harness-makers and stock tenders. Any matters on his division over which there was a dispute were adjusted by him. Within each division was a local agent who usually acted as clerk for the division agent in addition to his other duties.

Below the division agent in importance to the operation was the messenger – in popular stories, the messenger “rode shotgun”. He sat with the driver and had entire charge of the mail until it was delivered to the next messenger.

The position of express messenger was one of the most responsible held by any employee on the stage line. He was entrusted with the safety of any valuable packages being transported – often a fortune was placed in his charge. Knowing that large sums of money were often onboard the stages was a temptation to highwaymen; there were many places along the sparsely settled road where two or three persons could holdup a coach or rob a load of passengers – or even hold up a squad of soldiers.

Given the risk to the messenger, his pay was not equal to that of other employees. His duty route was longer than the driver’s; he was required to ride outside with the driver six days and nights, catching what sleep he could from time to time while the stage was moving, exposed to all kinds of weather, all while required to constantly guard the mail and any valuables. He received $62.50 a month plus meals while on the road, but was idle nine days out of twenty one – so that his actual (paid) working time was reduced – on the other hand, his days of exposure to risk was less as well.

Three messengers were employed on the line between Atchison and Denver, three more between Denver and Salt Lake, and another three between Salt Lake and Placerville. One would be going west, one headed east , while the other would be lying over a week at Atchison, Denver or Salt Lake resting after making a round trip over his division.

The “box” was carried in the front boot under the driver’s seat on the regular coaches. If there were enough express packages to fill the stage, the company would run a special with no passengers – but it was uncommon to not have at least one passenger; a usual run often had at least six, some for the full run to Sacramento. Shipping on the eastern end to Denver for express packages other than gold dust, coin, or currency, was one dollar per pound.

In 1863, traffic to the mining region of Denver, Central City and Black Hawk was heavier than for all other points combined, making the South Platte River route the most heavily travelled and most lucrative line of the company – it is estimated that 20,000 people per year travelled the route.

There were about 50 drivers per division on the route and he was considered the most interesting person on the stage line. One passenger later wrote: “Most of them were sober, especially while on duty, but nearly all were fond of an occasional ‘eyeopener’ … they were also fond of tobacco and rolled out ponderous oaths, when things did not go to suit them.” The drivers considered his whip worth its weight in gold, it being a sign of the magnitude of his position. Some were so expert that they could sit in their seats and pick a fly off the lead horse while galloping down the trail.

Almost every driver took pride in keeping his stock in fine condition. The animals would be inspected by the division agents and other officials who often made inspection trips over the line, examining closely every animal and harness. The driver kept harnesses in good condition – they were well oiled and even after years of constant use looked almost as nice as the day it was new.

Drivers of the line

The lowest ranking employees were the stock tenders. These men were not of the best of society, often being “fugitives from justice” – which may have meant avoiding the draft for the kerfluffle in the east or being former Confederate POWs who chose western life (and swearing an oath to the Union) over POW camp. The stock tenders were always in attendance at the “swing stations,” usually only a one room structure of trimmed logs, a sod roof and dirt floor. No wonder few if any remains still exist.

Like any job. working for the Overland had its problems but pay was not one of them. Drivers would receive from $40.00 to $75.00 a month plus board; stock tenders received $40 to $50 not including board; carpenters $75; harness makers and blacksmiths $100 to $125 a month and division agents from $100 to $125 – which was upped to $200 during the Indian troubles. A private in the army only received $13 a month.

The mail contract paid the company $365.000 per year but additional receipts from passenger and express business were even larger, often being from $150,000 to $200,000 per month. The fare for the full distance – from Atchison to Placerville – was $600. Fares between points ranged from twelve and one-half (1 bit) to fifteen cents a mile. Passengers were allowed 25 lbs of luggage; extra baggage, 75 cents to $1.50 per pound. When the mining excitement ran highest, the coaches were carrying full loads both ways (and fares were increased). Each coach might carry twelve passengers and nearly half a ton of mail and express matter, in addition to the driver and messenger. Depending on road conditions, the coach would average between 6 and 16 miles an hour. In order to meet the schedule, an average of a bit over 110 miles needed to be covered every day

Equipment was usually of the very best; the usual Concord coach was built by the Abbot-Downing Company of Concord, NH. There were about 100 of these high-end coaches on line at any one time – each costing about $1300 and built for endurance. A standard set of 4 harnesses per coach cost about $150. Feed for the stock was one of the important items of expense – each station allocated from forty to eighty tons of hay annually – hay costing from fifteen to forty dollars a ton. Feed was allocated at about twelve quarts of corn daily per animal; costing from two to ten cents a pound.

No animal could excel the mule for endurance, but horses were used when speed over endurance was preferred. Mule teams in particular were used on the eighteen mile stretch through sand from Junction and Bijou Creek to Fremonts Orchard. A team used on that stretch would use five mules. The two heaviest were the wheelers, another two forward of them, and the lightest hitched as a single in the lead. Mules seemed to be much better adapted for work in sandy regions than horses and were used in such places.

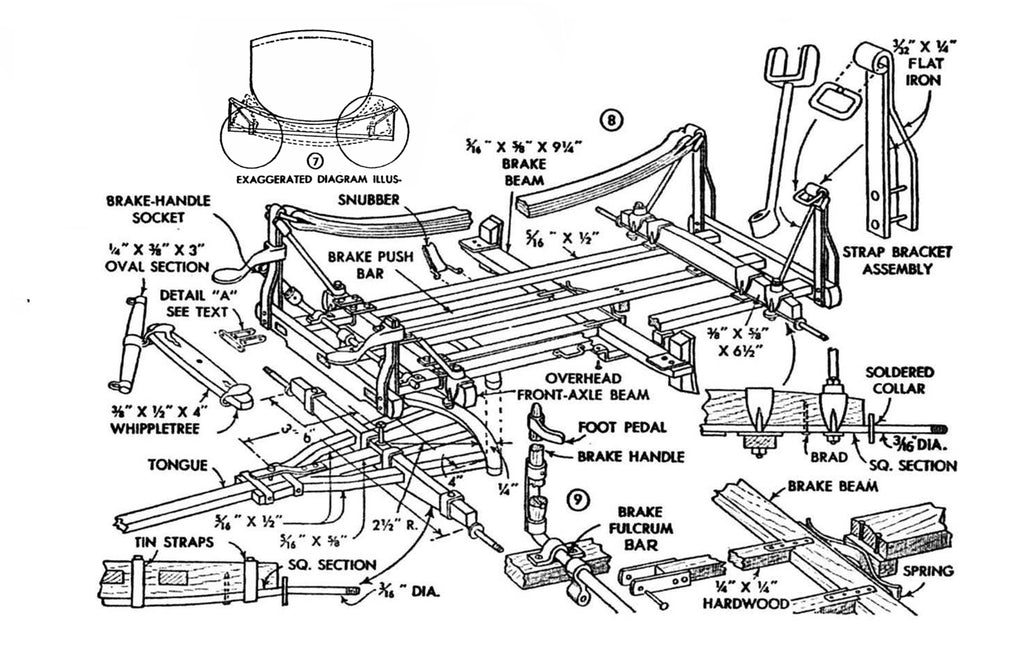

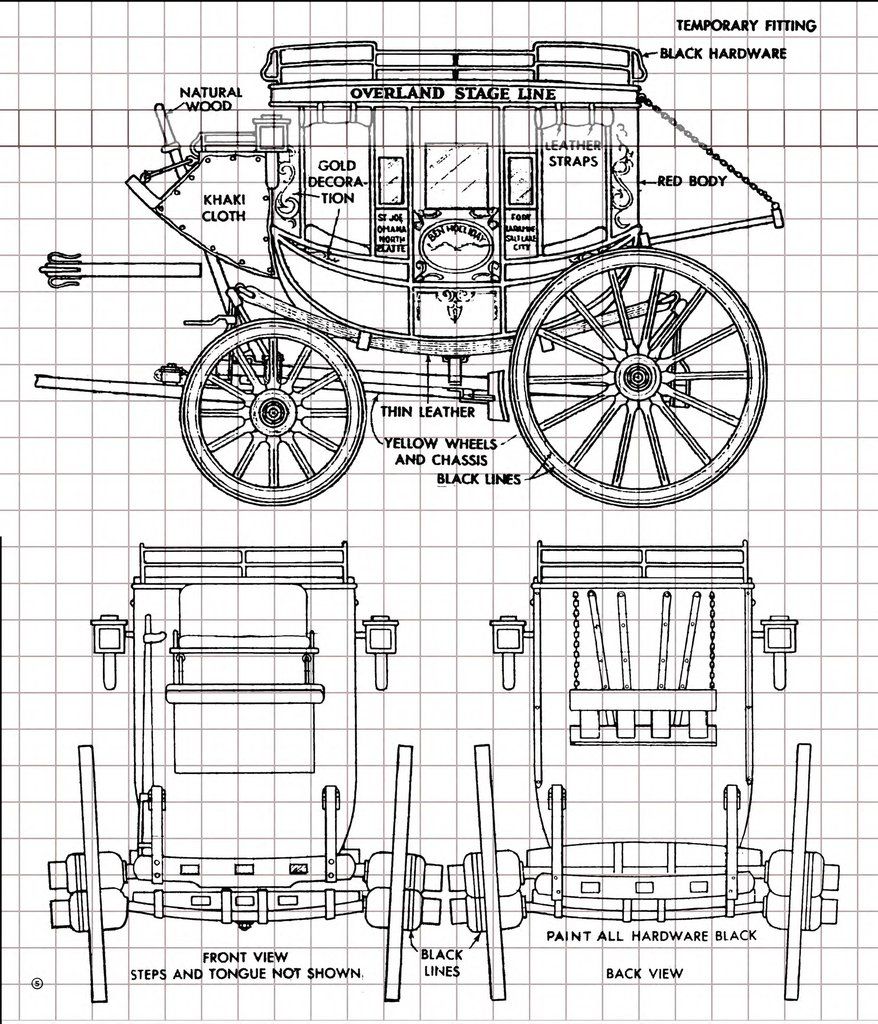

The Concord coach weighed 2,500 pounds, were 8 1/2 ft long and stood over 9 feet tall. The body was suspended on straps attached to the frame. Wheels were wooden with iron straps as tires. The driver applied brakes by pushing on a foot-lever which forced wooden blocks against the rear tires.

Although taken from plans for a model, the following images give an idea of the construction of a Concord coach.

There were three bench seats inside; the bench seats at the front and rear had limited headroom; the center bench had no backrest but had a leather harness suspended across the coach by straps from the roof. The coach could accommodate another six passengers on the roof.

Luggage was carried on the back or roof if room; valuables were carried in a compartment under the driver’s seat.

Some stations along the trail were built of cedar (juniper) logs; some of frame construction which cost about $2,000. About three-quarters were built of adobe or sod. The home stations were often frame type, built of lumber hauled from south of Denver. Home stations were usually provided with sheds, outbuildings, and other conveniences.

“The stables were built 50 feet long by 25 feet wide, and they had large granaries built to them, and they were battened up, attached and shingled roof. The houses were shingled roofs, and had upright bolts, and were battened tight; very neat kitchen and dining room; most of them had four rooms besides the dining-room and kitchen“.

Drivers were changed at the home stations – located about every 50 miles. The home stations also provided food for passengers – between Julesburg and Denver the meals cost $1.00. The food served usually included bacon, eggs, hot biscuits, tea, coffee, dried peaches, dried apples, dried apple pie, some beef, bison, and canned fruit and vegetables. Groceries were often available along with blacksmith services. Hay and wood were sold at some stations; however, travelers in the know carried their own wood tied under the wagons.

For the most part, swing stations where teams were changed were placed every 10-15 miles between home stations. Much of the South Platte route was across sand dunes creating a hard pull for the stage teams which were often of mules along this section. Among the worst was the section between Bijou Creek and Fremonts Orchard. An extra team of mules, called a spike team, was used and even then the teams went no faster than a walk. It took almost a full day to travel between Julesburg and Denver.

Each of the swing stations built along the 250 mile long stretch along the South Platte were built to similar construction. Most of the buildings were constructed by the stage company; each were usually nearly square, one-story log structures having one to three rooms or muslin partitions used to separate the kitchen from the dining-room and sleeping quarters.

The roof was supported by a log placed across gable to gable which supported closely placed cross poles as rafters. Willow branches served as “shingles” with a layer of hay covered with sod; then the whole covered with a sprinkling of coarse gravel to keep the dirt from being blown off. The logs used came from the southern part of western Nebraska.

The home stations were more solidly constructed – often of frame and two or three times larger than the swing stations.

The importance of the stage stations did not escape the attention of Indians intent on blocking American expansion into the west. The hostilities with the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho which led Holladay to abandon the Oregon Trail eventually spread to the Overland Trail. Fort Halleck was established near Elk Mountain in the fall of 1862 with elements of the 11th Ohio Cavalry stationed there to protect the trail. Troops were posted at the stage stations east from LaClede beginning in 1863.

Indian raids increased in 1865 along the South Platte and Wyoming sections of the route after the Sand Creek massacre in late 1864. Many of the stations along the South Platte were destroyed; some never re-built. Raids along the route were so bad, all service stopped in the summer of 1865.

Between late May and late June, there were significant attacks at the Bridger Pass, Sage Creek, Pine Grove and Sulphur Springs stations in Wyoming. In early June, the Washakie Station was attacked with one man was wounded and nine cavalry horses driven off. Two emigrants were killed in the Sage Creek area that same day and the country was raided for 50 miles along the mail line. A troop from the 11th Ohio Cavalry were sent from Fort Halleck to open up the mail route. The Pine Grove and Bridger Pass stations were found deserted; the employees had gathered at the Sulphur Springs station. During this period, each station in the affected area supported a small group of soldiers to protect the mail. Mounted cavalry also escorted the stage at times.

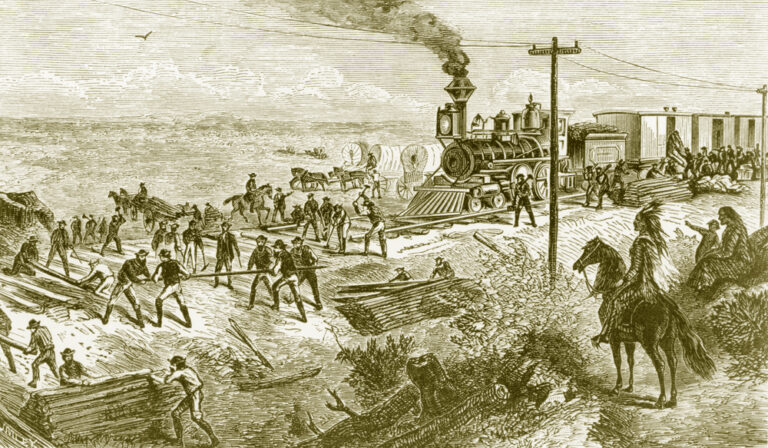

Construction of the transcontinental railroad began after the war ended in 1865, although planning had begun several years earlier. Union Pacific surveyors looked at the Overland Trail as a potential route through Wyoming but chose a more northerly route across the Red Desert. Ben Holladay sold the Overland Stage Line to Wells Fargo while the Union Pacific was still building across Nebraska in 1866 – Wells-Fargo misjudging how fast the rails would be laid.

The railroad reached the Colorado border in June, 1867. Third Julesburg (or Weir) was founded as a Union Pacific end- of-track town and consisted of a few tents at the time the first train arrived on June 25. The town later had a population of around 2500 people, 120 structures, and about 100 people in Boot Hill cemetery. After the railroad reached Julesburg – where the rails swung north, the stage continued to serve the area to and beyond Denver.

A rival corporation known as the “Butterfield Overland Despatch” had absorbed the Smoky Hill line running through Kansas. The territorial legislature of Colorado changed the name of the now consolidated lines to the “Holladay Overland Mail and Express Company.” This name was used until nearly all the stage and express lines of the west were bought and consolidated under the name of “Wells, Fargo & Co.’s Express.”

Once the railroad reached Cheyenne in November, 1867, the stage line along the South Platte River was severely curtailed, and most of the people and businesses in Third Julesburg moved to Cheyenne. Stage service to Denver from Third Julesburg decreased on both the Overland Trail and the Fort Morgan Cutoff but stages still went south from Cheyenne to Denver. However, by the winter of 1867-1868, freighting by wagons had nearly ended in this area.

The first train reached Denver in 1870 and the last stage coach came into Denver on the Overland Trail. The rail from Cheyenne reached Denver in June, 1870 ending the stage traffic north into Wyoming.

After abandonment, the now deserted stations were scavenged for building materials; remnants were obliterated when the land was plowed or leveled for irrigation. The South Platte has flooded many times over the years; the location of the river itself has shifted in places and has possibly washed away some stations and parts of the trail, particularly around Fremonts Orchard. The trail has been subjected to wind erosion and has been covered by wind-blown sand; however, many segments of the Overland Trail along the South Platte were not farmed and sections of the trail are fairly well extent – some sections becoming county roads, some now ranch roads.

Wells Fargo continued running stages west from the nearest station on the Union Pacific railhead through 1868. As the railroad was built across Wyoming, the stage stations were closed sequentially from east to west and military posts such as Fort Halleck were replaced by new forts along the railroad. The era of transcontinental stagecoach traffic through Wyoming ended when the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads met at Promontory Point, Utah in May 1869. Wells Fargo sold its stagecoach holdings in October 1869.

Wells-Fargo was not alone in misjudging the time expected to complete the railroad. The railroad companies, having an army of railway builders constantly at work, kept steadily shortening the stage rides. The railroad was completed years earlier than believed possible with the result of its early completion being a severe financial blow to the purchasers of the Overland Stage, and they lost heavily. They had between $50,000 and $75,000 worth of surplus stagecoaches; these were sold for surplus at less than one-third the original cost.

Although local stage traffic did not stop, the Lincoln Highway became the principal automobile road across southern Wyoming in 1913. Auto stages – the forerunners of bus service – replaced the horse-drawn coach. Portions of the stage route between Point of Rocks and Granger were incorporated into the early Lincoln Highway – now a service road off I-80. Other segments of the trail are in use now as local ranch roads. Eventually, the stations and majority of the Overland trail were abandoned to time.

The last stagecoach robbery occurred outside Jarbridge, Nevada near the Idaho line in 1916. The driver was killed and $4,000 was stolen. Three suspects were arrested shortly afterward. The $4,000 was never recovered and is assumed hidden in the Jarbridge canyon – a well-documented case of “hidden treasure”.