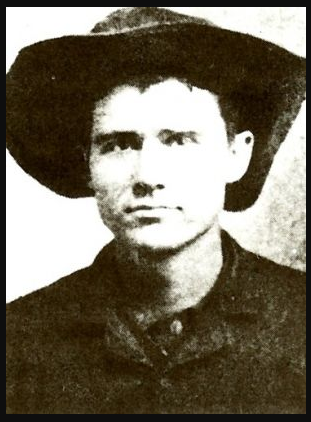

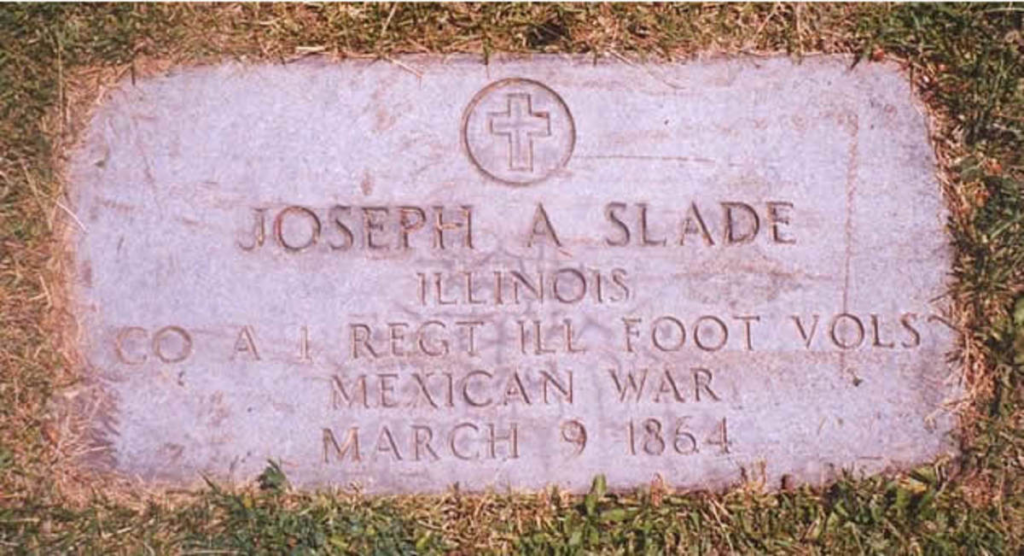

Joseph Alfred Slade was born in Carlyle, Illinois on January 22, 1831, one of three sons of Charles and Mary Slade. One son William was an officer in the Mexican War, another, Charles Jr, died in the Civil War, and Jack, who became the famous gunfighter of this story. Charles Sr was a prominent politician who founded the town of Carlyle. He died of cholera in 1834. Mary remarried in 1838, having another son with her new husband.

Jack married Maria Virginia (maiden name unknown) in 1857 while a teamster and wagon-master. After a stint as stagecoach driver, he became an agent for the precursors to Ben Holladay’s Overland Stage Company, including operations of the Pony Express. Jack ended up killing – righteously, it is told – another employee in 1859 and received the reputation of a gun-slinger. Effective at enforcing order for the company’s interests, “the scourge of outlaws”, the Overland company promoted him to division superintendent with orders to replace the thieving agent in Julesburg, Jules Beni, and that’s the story these words tell.

Fame went to Jack’s head as did drinking. He was later fired by the Overland company, moved to the gold fields of Montana where he was hung by vigilantes in Virginia City, Montana on March 10, 1864.

The stories:

Frank Root (1901):

In its palmiest days, during overland staging and freighting, old Julesburg had, all told, not to exceed a dozen buildings, including station, telegraph office, store, blacksmith shop, warehouse, stable, and a billiard saloon. At the latter place there was dispensed at all hours of the day and night the vilest of liquor at “two bits” [25¢] a glass. Being a “home” station and the end of a division, also a junction on the stage line, and having a telegraph office in the southeast corner of the station, naturally made it, in the early 60’s, one of the most important points on the great overland route. It was also the east end of the Denver division, about 200 miles in length.

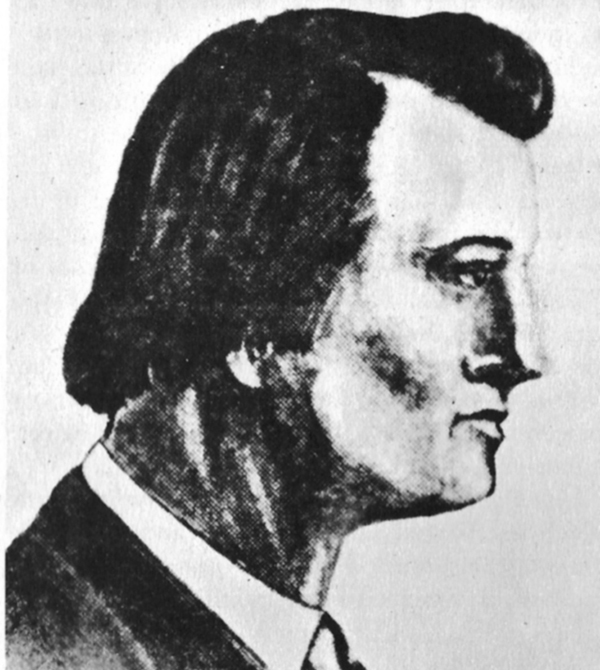

When the express line was moved up north to the Platte, Beverly D. Williams, of Denver — formerly of Kentucky, now of Arkansas — was given the general management of the Jones & Russell Stage Company’s business, Jules was placed in charge of the station bearing his name that had been built on the south side of the Platte opposite the mouth of Lodge Pole creek [where Ft Sedgwick was later established]. Socially Williams was one of the best fellows in the world, but as manager of a great stage company’s property on the frontier he was not a success. He knew very little about the plains, it was said, and much less of the people residing there. He seemed to look upon every one whom he employed as honest, capable, and efficient, when in reality some of them were at heart scoundrels and thieves, who systematically stole the company’s property. Because a man knew the plains over which the stages ran, Williams would venture to hire him as a station keeper. Thus it was that he had in his employ a number of unprincipled rascals, who really ought to have been boarding at the penitentiary instead of living at the expense of the stage officials.

Having been nearly bankrupted by what they believed bad management, the company decided to make a change, and Ben. Ficklin was employed as superintendent. He was a good man for the place, and one who thoroughly understood everything in connection with staging. There was no part of the overland route between the Missouri river and the Golden Gate with which Ficklin was not familiar. He was a man with force of character; likewise he had the “sand” and courage to carry out his plans. From the date of the change in management there was no longer peace and harmony.

One of the first important moves made by Ficklin on taking charge was the placing of Jack Slade on the road as a division superintendent, having charge of the Sweetwater division, extending from Julesburg to Rocky Ridge, on Lodge Pole creek. Naturally there were some ” delinquents ” on the line, and Slade exercised his prerogative and made them come to time. He was an untiring worker, at first putting in the most of his time night and day for the interest of the company by which he was employed, as well as doing everything he could for the comfort of the passengers. Special attention was given by Slade to the stage stations; particularly was this so with the one at Julesburg.

The discoveries made by Ficklin showed Jules to be a thief and a scoundrel of the worst kind. Jules was at once made to settle with the stage company. He made a vigorous protest, but had to liquidate, knowing there was no escape. But he was determined on revenge, and accordingly lay in ambush one day and gave Slade the contents of a double-barreled shot-gun, which the latter carried off in his person and clothes. The next stage that passed over the road had Ficklin aboard and his first duty was to hang Jules, after which he drove on. Jules, however, was not ready to die just yet. Before he had quite ceased to breathe some one came along and cut the rope, and Jules revived and fled from that part of the country, remaining for a time in obscurity.

But there was revenge in Jules’s heart. He was bound to get even, and he never could get rest until he had obtained what he conceived to be his due. Going up on the Rocky Ridge road with a party of his sympathizers, it was not long thereafter until all sorts of depredations were committed on the stage company’s property. How to stop these depredations was a matter of serious consideration. In the meantime Slade had recovered from the wounds inflicted by Jules, and Jules having been seen by some of the drivers, who informed Slade, he asked to be transferred to the scene of the depredations.

Knowing Slade to be a terror to all evil-doers, Superintendent Ficklin made the change. For some time Slade rode back and forth over the line, carefully surveying with his keen eyes every rod of the route. In due time he found where Jules and his cowardly gang were located. With a party of resolute, determined men, Slade came along one day and caught them off their guard. A desperate fight took place. In the engagement Jules was badly wounded and, with no power to resist, he was tied by Slade, and stood up against the corral, when his ears were cut off and nailed against the fence, and bullet after bullet was fired into his body. Thus ended the career of one of the worst men that, up to the early ’60’s, had ever infested the overland line. For weeks following this barbarous act, one of Jules’s ears remained nailed to the corral, while the other, it is said, was taken off and worn by Slade as a watch-charm.

When Slade went into the employ of the “Overland” he was regarded, so far as known, as a fair sort of a man. He had driven, and was an experienced stage man — an important requisite — and no one on the line was ever more useful at the time. He had been a division agent, with headquarters at Fort Kearney. He was a sort of vigilance committee single-handed, and it was through his efforts that the line was eventually cleared of one of the worst gangs that ever held forth on the plains. Jules and his crowd having been effectually disposed of, and matters elsewhere having been attended to by Ficklin’s orders, the line was shortly put in perfect order, and from that time on the stages ran with great regularity.

Joseph A. Slade was originally from Clinton county, Illinois. In the later ’50’s and early ’60’s, while employed on the “Overland,” he often visited Atchison, and would occasionally have a “high, old time” when in company with some of the wide-awake stage boys. He was not the bad man at that time, however, that he afterwards turned out to be, for while in the employ of the stage company he was faithful to the trusts reposed in him.

But Slade, important as his services had been to the Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express Company during the period of its darkest days, finally went the wrong way. He soon lost all character and was unable to bear up under all the excitement he had gone through. Surrounded by all the alluring temptations and vices of the frontier, he commenced drinking, and finally became a terror to those to whom, in the earliest days, he had been a most-trusted friend, and fell into the ways of the ones he had so long fought on the overland express line.

Jules Beni established a trading post and ranch – “wickedest city on the plains.” – downstream 1 mi from the mouth of Lodgepole Creek on the south side of the South Platte. [Lodgepole Creek is on the north side of the river where Ovid is now] The site became a stage station but after Beni became the station manager, stage robberies became a constant problem. Beni was suspected and the company replaced Beni with Jack Slade, who became a division superintendent.

The two continuously argued; Beni ambushed Slade in 1860, shot him five times but Slade survived and Beni was arrested and forced to leave town. He returned a year later, continued to steal horses, and attempted to kill Slade again whereupon Slade tied Beni to a fencepost and shot his fingers and ears off. Some say Slade killed Beni at the time, putting the gun in his mouth and pulling the trigger – others that Beni was later killed by Slade’s men in August 1861.

Mark Twain mentions meeting Slade while Slade was operating the Virginia Dale Station in August 1861. Although Twain referred too Slade as “a vicious killer of 26 men”, Slade is only known to have killed one man named Andrew Ferrin … although legend – true or not – has it Slade killed Beni in 1861 while Beni was tied to a fence post.

Slade had a drinking problem and was fired by the Overland Company in November, 1862. He was lynched by vigilantes in Virginia City, Montana after a drunken rampage in March 1864.

Some say this occurred outside Julesburg, some say at a Wyoming ranch

For a completely different version, see Rottenberg’s version at the end

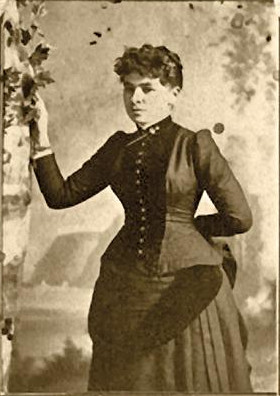

Slade stood out even among the many rabble-rousers who inhabited the wild frontier-mining town of Virginia City, Montana. When he was sober, townspeople liked and respected Slade, though there were unconfirmed rumors he had once been a thief and murderer. When drunk, however, Slade had a habit of firing his guns in bars and making idle threats. Though Slade’s rowdiness did not injure anyone, Virginia City leaders anxious to create a more peaceable community began to lose patience. They began giving more weight to the claims that he was a potentially dangerous man. . . . Finally fed up with his drunken rampages and wild threats, on this day in 1864 (October 10) a group of vigilantes took Slade into custody and told him he would be hanged. Slade, who had committed no serious crime in Virginia City, pleaded for his life, or at least a chance to say goodbye to his beloved wife. Before Slade’s wife arrived, the vigilantes hanged him.

Slade’s wife, Virginia, rode twelve miles at breakneck speed in vain to his rescue. Refusing to have her husband buried where he would not be remembered kindly, she had his coffin lined with tin and zinc to prevent leaks and filled it with whiskey — the best preservative available at the time. The coffin sat in the front room of her small house in town for three months until the road thawed and, in June, she had the coffin loaded onto a stage to Salt Lake City. There he was interred in a pauper’s grave in Block 4, “to be removed to Illinois in the fall,” according to the city’s then-sexton.

Afterwards, “Life sort of overwhelmed” Virginia. She was married twice more and wound up in St. Louis, just 50 miles from Carlyle, but she either never tried or was never able to have her husband dug up and reburied there.

Buried on July 20, 1864, Jack Slade is still interred in a pauper’s grave at the Salt Lake Cemetery.

The story as told by Dan Rottenberg, biographer and author of “Death of a Gunfighter: The Quest for Jack Slade, the West’s Most Elusive Legend“

In the fall of 1859, Slade was transferred to the central division, the most dangerous stretch of the struggling stagecoach line, which in the interim had been sold, reorganized and renamed the Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company. The Pony Express, a horseback relay system that would work with the stage line to deliver the mail, also began to take shape in 1859. Slade bought the right kind of horses (fast but tough) to make the Pony work (which it did from April 1860 until October 1861). But his main orders were to “clean up the line”—which meant, above all, replacing one Jules Beni, the corrupt and incompetent station keeper at Julesburg. Beni had been allowing his outlaw friends to steal company stock, which he would then “retrieve” for a reward charged to the company.

After taking over, Slade quickly established order by conspicuously capturing and hanging a few robbers and horse thieves and letting word of mouth drive out the rest. But in March 1860, his nemesis ambushed him as he entered the restaurant at Julesburg Station. Beni fired as many as a dozen times with both revolver and shotgun before fleeing to Denver. “I never saw a man so badly riddled,” said station keeper James Boner of Slade. “He was like a sieve.”

Remarkably, Slade survived this barrage. In a tribute to his value, the Central Overland transported him almost 1,000 miles by stagecoach and rail to St. Louis, where surgeons removed some of the lead from his body. By June, Slade was back at work, his domain as superintendent extended to cover nearly 500 miles from Julesburg west to the Rockies.

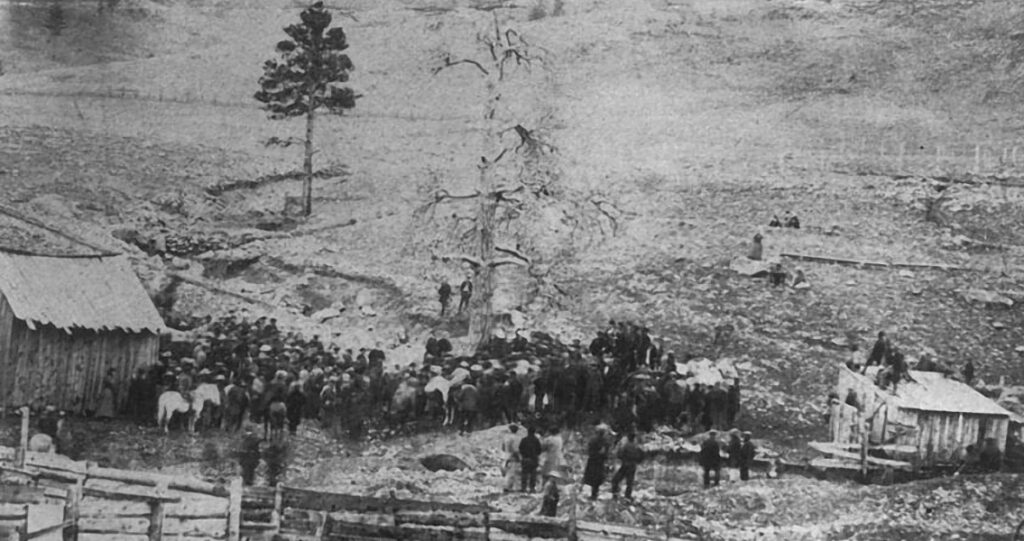

The code of the West demanded Slade exact revenge for the shooting. The Central Overland’s new owner, Ben Holladay, impatiently implored him to “get that fellow Jules, and let everybody know you got him.” Yet for more than a year, while scourging his division of outlaws, Slade made no move to pursue Beni. Then, in August 1861, the 52-year-old Beni foolishly returned to Slade’s division to secure some stock, all the while spouting threats and boasting he was “not afraid of any damned driver, express rider or anyone else in the mail company.” Slade posted a $500 reward for his capture and sent four riders after him while Slade followed in a stagecoach.

According to the most reliable account of what happened next, two of Slade’s men, Nelson Vaughan and John Frey, overtook Beni, wounded him in a gunfight and captured him. They then bound Beni to a packhorse and started for Sochet’s ranch at Cold Spring Station (in present-day Wyoming). To their dismay, Beni died before they arrived. Fearful of losing the posted $500 reward—and of arousing Slade’s wrath—once at Cold Spring, they tied Beni in a seated position to the snubbing post in the corral. Soon thereafter Slade pulled into Cold Spring.

“I suppose you had to kill him,” Slade remarked, “and if you did, you do not get any reward.” Vaughan and Frey insisted Jules was not yet dead, only wounded.

“He’s out in the corral.”

When Slade walked out back to the corral and saw Jules’ inert body lashed to the fence, he said, “The man is dead.” Again Vaughan and Frey insisted that Beni was only playing possum. “I’ll see whether he’s playing possum,” Slade said, taking his knife and slicing off an ear. When Jules did not flinch, Slade remarked, “That proves it, but I might just as well have the other ear,” and took that as well. The gesture— the only barbaric act ever attributed to Slade, at least against a human—added yet another page to his legend.

After Beni’s death, Slade’s reputation was such that Mark Twain referred to him as “a man whose heart and hands and soul were steeped in the blood of offenders against his dignity.” Yet despite his Mr. Hyde–like mutilation of his nemesis, Slade had not gone off half-cocked after Beni and had most likely not been the one to actually kill him. Slade even turned himself in at Fort Laramie. Officers there did not press any charges; in fact, some of them had advised Slade to kill Beni.

Subsequent re-tellings of the Beni killing, explorer and Slade acquaintance Nathaniel Langford noted in 1890, were “false in every particular. Jules was not only the first, but the most constant aggressor.” Slade’s actions were those of a levelheaded and competent division agent who would broker no threat against his stage line. But in the aftermath, as Slade began indulging in his own fierce image, carrying one of Jules’ ears with him as a souvenir, cracks started to emerge in his professionalism.