[most of the maps may be viewed at higher resolution by right-clicking and viewing in a new window]

“It’s plagiarism to copy from one source; it’s research if copied from many sources“

I used information from many sources to compile the following discussion. Funny how many of them used the exact same wording in descriptions of various events and places …

Many of those sources about the Colorado portion of the route – The South Platte Route – can be traced back to the personal reminiscences within The Overland Stage to California by Frank Root in 1901. Frank Root had held various positions with the Holladay Overland Stage Line, primarily as station agent at age 26 in 1863 for $1000/year at Latham, Colorado – a major home station near modern Greeley. Additional information came from other sources, including other reminiscences, original plat maps of the late 1860s/early 70s, research in Wyoming and Colorado, and bits and pieces scraped together from here and there.

And some … my on-site experiences in the region.

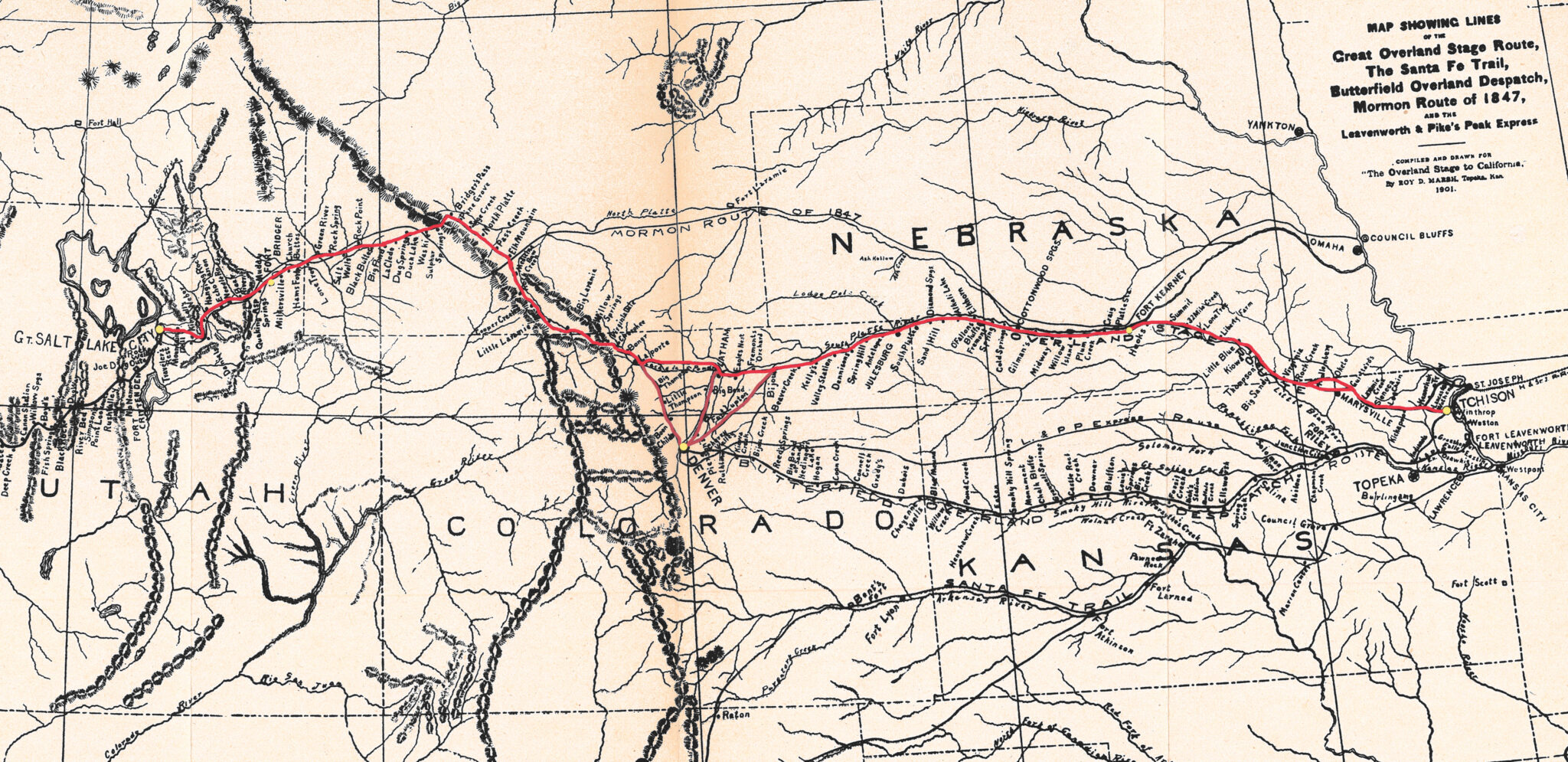

The original stage line – The Butterfield Overland Mail – ran along what was referred to as the southern route from 1858 to 1862. Two originating points: Memphis and St Louis to join at Ft Smith, then a single route south to roughly follow just north of the Mexican border to LA and eventually up to San Francisco. It took just shy of 25 days to get from San Francisco to St Louis with twice weekly service. There were about 140 stations and 100 coaches on this line. After 1859, the fare was about $200 for the entire 2700 mile distance. There were no stops for sleep and barely any for food. There were bandits and Indians though.

One passenger stated:

“Had I not just come out over the route, I would be perfectly willing to go back, but I now know what Hell is like. I’ve just had 24 days of it.“

When that little squabble back east started in early 1861, the Butterfield company – holding the contract to deliver US mail – closed the southern route and moved to serve the then-lucrative US-controlled route from Salt Lake City through Carson City/Virginia City and on to Placerville, California (roughly along now-back roads from Salt Lake, skirting south of the Dugway Proving Grounds to Ely, NV and then more or less along today’s US50 from Ely to Placerville, California). The re-routed organization was called the Central Overland Route and was the main “highway from the east to California” until the Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869 … although smaller stage lines continued to serve settlements away from the railroad into the 20th century.

This isn’t the route segment I want to speak of.

Ben Halloday’s Overland Stage Company

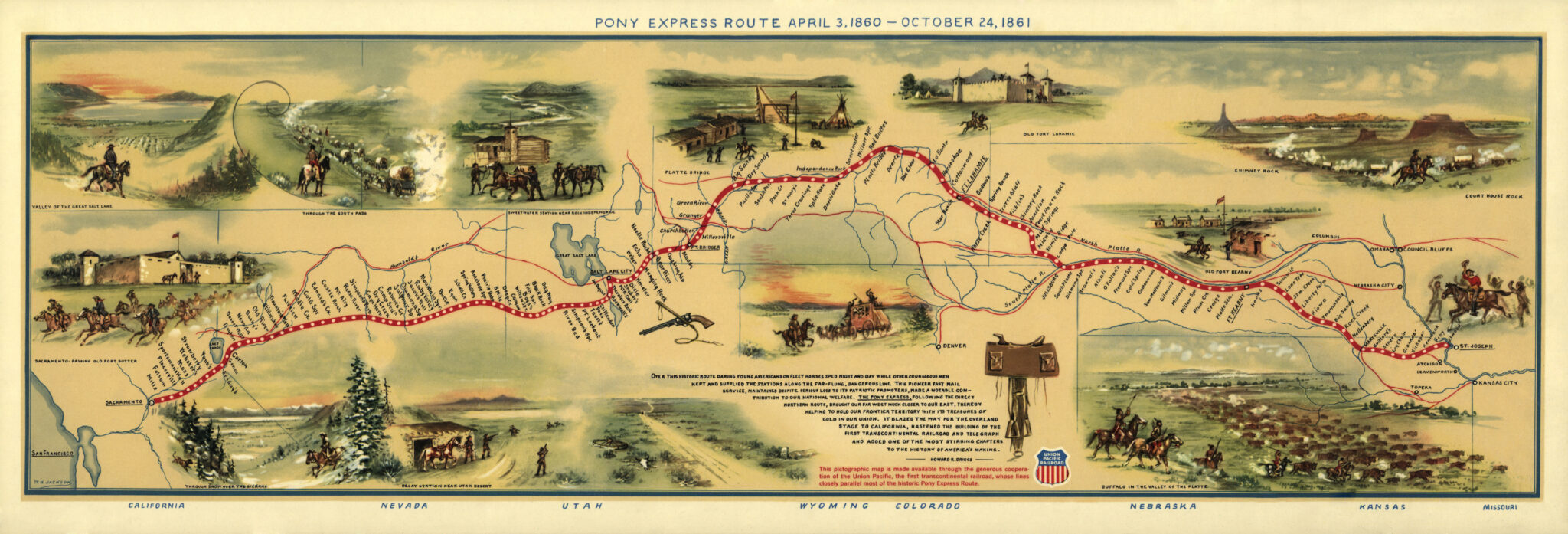

Meanwhile, the Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express Company (COCPPEC) held the mail contract between St Joseph, Missouri and Salt Lake City with a branch to Denver. This company also operated the Pony Express mail route … which only operated for 18 months when in 1861, the line went bankrupt and the transcontinental telegraph line was opened. Except through Colorado and Wyoming, the Overland Route eventually closely followed the Pony Express Trail up through Ft Laramie and through South Pass – the “Northern Route”.

A subsidiary of the Russell, Majors, and Waddell freight line, the COCPPEC survived after a bond scandal forced the freight portion of the company into bankruptcy. However, when the mail contract expired, Ben Holladay purchased the assets of the COCPPEC and formed the Overland Stage Company.

The Holladay route originally followed the Oregon Trail through South Pass, Wyoming but Indian troubles caused the line to be moved south following a path over Bridger Pass … the so-called Central Route. Holladay ran this business until November, 1866 when he sold out to Wells Fargo for $1.8 million. After this time, Wells Fargo pretty much had a monopoly on stage travel in the west which lasted until the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869. The route continued to be used for many years after under different management and much of it today is still used by modern highways.

After Holladay bought out the near-bankrupt COCPPEC towards the end of 1861, he reorganized the company and changed to name to the “Overland Stage Line“. He spent a considerable amount in making it the best-equipped stage line in the country. The stages were of the Concord type driven with the best horse and mule teams available. He also hired the best people, from the division agents down to the lowest stock tenders. His main goal was to improve the transportation of the mail as well as improving travel for his passengers.

From Ft. Kearney to Big Springs, Nebraska, the route generally followed what is now I-80 on the south side of the Platte River though Nebraska (later, the route of the Transcontinental Railroad also followed the Platte on the north side of the river along what is now US30). The trail split near Big Springs, Nebraska: one route heading towards Ft Laramie, the other along the South Platte River (now I-76) – also splitting at Julesburg (to allow for obtaining supplies), again later splitting near what is now Ft Morgan into a southwest route to Denver. The main route continued along the river, passing through Latham (now Greeley) where it left the South Platte and followed the Cache la Poudre River (US34) to LaPorte, north into Wyoming (US287), and on to Salt Lake City. As Denver grew, the main route turned south at Latham to Denver, then back north – along US287 – and re-joining the original trail at LaPorte.

Eugene Ware wrote a memoir, The Indian War of 1864, describing the stage operation:

The stage stations were about ten miles apart, sometimes a little more and sometimes a little less, according to the location of the ranches. Stores of shelled corn, for the use of the stage horses, were kept at principal stations along the line of the route. Intermediate stations between these principal stations were called “swing stations,” where the horses were changed. For instance, the horses of a stage going up were taken off at a swing station, and fed; they might be there an hour or six hours; they might be put upon another stage in the same direction, or upon a stage returning. It was the policy of the stage company to make the business as profitable as possible, so it did not run its coaches until each coach had a good load, and they were most generally crowded with persons both on the inside and on top. Sometimes a stage would be almost loaded with women. From time to time stage company wagons went by loaded with shelled corn for distribution as needed at the swing stations. All of the coaches carried Government mail in greater or less quantities. Occasionally when the mail accumulated, a covered wagon loaded with mail went along with the coaches. These coaches were billed to go a hundred miles a day going west; sometimes they went faster. Coming east the down-grade of a few feet per mile enabled them to make better time. They went night and day, and a jollier lot of people could scarcely be found anywhere than the parties in these coaches.

The coaches were all built alike, upon a standard pattern called the “Concord Coach,” with heavy leather springs, and they drove from four to six horses according to their load. The drivers sat up in the box, proud as brigadier-generals, and they were as tough, hardy and brave a lot of people as could be found anywhere. As a rule they were courteous to the passengers, and careful of their horses. They made runs of about a hundred miles and back. I got acquainted with many of them, and a more fearless and companionable lot of men I never met. There seemed to be an idea among them that while on the box they should not drink liquor, but when they got off they had stories to tell, and generally indulged freely. They gathered up mail from the ranches, and trains, and travelers along the road, and saw that it reached its destination. They had but very few perquisites, but among others was the getting furs, principally beaver-skins, and selling them to passengers. Most of them had beaver-skin overcoats with large turned-up collars. We soon understood the benefits of these collars, and the officers of our post put large beaver collars on their overcoats, and the men of the company fitted themselves out with tanned wolfskin collars, which were equally as good. Wolves were so numerous that there was quite an industry in shooting or poisoning them, and tanning their skins for the pilgrim trade.

[I sometimes wonder if by “wolves”, they meant coyotes …]

Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) described a station and passengers in Roughing It (not that Mark Twain ever embellished a good story):

The station buildings were long, low huts, made of sun-dried, mud-colored bricks, laid up without mortar (adobes, the Spaniards call these bricks, and Americans shorten it to ‘dobies). The roofs, which had no slant to them worth speaking of, were thatched and then sodded or covered with a thick layer of earth, and from this sprung a pretty rank growth of weeds and grass. It was the first time we had ever seen a man’s front yard on top of his house. The building consisted of barns, stable-room for twelve or fifteen horses, and a hut for an eating-room for passengers. This latter had bunks in it for the station-keeper and a hostler or two. You could rest your elbow on its eaves, and you had to bend in order to get in at the door. In place of a window there was a square hole about large enough for a man to crawl through, but this had no glass in it. There was no flooring, but the ground was packed hard. There was no stove, but the fire-place served all needful purposes.

There were no shelves, no cupboards, no closets. In a corner stood an open sack of flour, and nestling against its base were a couple of black and venerable tin coffee-pots, a tin teapot, a little bag of salt, and a side of bacon.

By the door of the station-keeper’s den, outside, was a tin wash-basin, on the ground. Near it was a pail of water and a piece of yellow bar soap, and from the eaves hung a hoary blue woolen shirt, significantly — but this latter was the station-keeper’s private towel, and only two persons in all the party might venture to use it — the stage-driver and the conductor. The latter would not, from a sense of decency; the former would not, because did not choose to encourage the advances of a station-keeper. We had towels — in the valise; they might as well have been in Sodom and Gomorrah. We (and the conductor) used our handkerchiefs, and the driver his pantaloons and sleeves. By the door, inside, was fastened a small old-fashioned looking-glass frame, with two little fragments of the original mirror lodged down in one corner of it. This arrangement afforded a pleasant double-barreled portrait of you when you looked into it, with one half of your head set up a couple of inches above the other half. From the glass frame hung the half of a comb by a string — but if I had to describe that patriarch or die, I believe I would order some sample coffins.

The furniture of the hut was neither gorgeous nor much in the way. The rocking-chairs and sofas were not present, and never had been, but they were represented by two three-legged stools, a pine-board bench four feet long, and two empty candle-boxes. The table was a greasy board on stilts, and the table-cloth and napkins had not come–and they were not looking for them, either. A battered tin platter, a knife and fork, and a tin pint cup, were at each man’s place, and the driver had a queens-ware saucer that had seen better days. Of course this duke sat at the head of the table. There was one isolated piece of table furniture that bore about it a touching air of grandeur in misfortune. This was the caster. It was German silver, and crippled and rusty, but it was so preposterously out of place there that it was suggestive of a tattered exiled king among barbarians, and the majesty of its native position compelled respect even in its degradation.

There was only one cruet left, and that was a stopperless, fly-specked, broken-necked thing, with two inches of vinegar in it, and a dozen preserved flies with their heels up and looking sorry they had invested there.

For those working the stations, life could be hard and lonesome. Except for the brief flurry of activity when the stage arrived, there was little to do except wait for Indian attacks. Neighbors were rare and far apart – each being twelve to fifteen miles apart. Entertainment would often take the form of dances which frequently took place at the home stations. It was not unusual for the women to ride on horseback or take the stage to travel some ten or thirty miles, dance away the greater part of the night, then ride back home. Some rode as far as fifty miles each way; neighbors and entertainment both being scarce.

By necessity, there were rules applied to the passengers. Wells-Fargo posted these:

1) Abstinence from liquor is requested, but if you must drink, share the bottle. To do otherwise makes you appear selfish and unneighborly.

2) If ladies are present, gentlemen are urged to forego smoking cigars and pipes as the odor of some is repugnant to the gentler sex.

3) Chewing tobacco is permitted, but spit with the wind, not against it.

4) Gentlemen must refrain from the use of rough language in the presence of ladies and children.

5) Buffalo robes are provided for your comfort in cold weather. Hogging robes will not be tolerated and the offender will be made to ride with the driver.

6) Don’t snore loudly while sleeping or use your fellow passenger’s shoulder for a pillow; he or she may not understand and friction may result.

7) In the event of runaway horses, remain calm. Leaping from the coach in a panic will leave you injured, at the mercy of the elements, hostile Indians and hungry coyotes.

8) Firearms may be kept on your person for use in emergencies. Do not fire them for pleasure or shoot at wild animals as the sound riles the horses.

9) Forbidden topics of conversation are: stagecoach robberies and Indian uprisings.

10) Gents guilty of unchivalrous behavior toward lady passengers will be put off the stage. It’s a long walk back. A word to the wise is sufficient.

Not all stations were up to the standards Ben Holladay expected and more than even a driver who spent a great part of his time on the box could stand. Some stations were filthy, even for a station far out in the boonies (one station at one time being known as “Dirty Woman”). At one station, things were not quite as clean as they might have been. One passenger who had perhaps not “roughed it” much, sat down at the table with the other passengers, and started making some comments about the food, complaining about the amount of dirt. The station operator at once spoke up:

“Well, Sir, I was taught long ago that we must all eat a ‘peck of dirt.’“

“I am aware of that fact, my dear Sir,” responded the passenger, “but I don’t like to eat mine all at once.“

Another:

“Along the Platte west of Fort Kearney, for a considerable distance, we for weeks had nothing in the pastry line except dried-apple pie. This article of diet for dessert became so plentiful that not only the drivers and stock tenders rebelled, but the passengers also joined in, some of them “kicking” like Government mules. As a few of the drivers expressed it, it was “dried apple pie from Genesis to Revelations.“

Finally the following gem, which very soon had the desired effect, was copied and sent on its way east and west up and down the Platte:

DRIED-APPLE PIES.

I loathe! abhor! detest! despise! Abominate dried-apple pies;

I like good bread; I like good meat, Or anything that’s good to eat;

But of all poor grub beneath the skies The poorest is dried-apple pies.

Give me a toothache or sore eyes in preference to such kind of pies.

The farmer takes his gnarliest fruit, ‘Tis wormy, bitter, and hard, to boot;

They leave the hulls to make us cough, And don’t take half the peelings off;

Then on a dirty cord they’re strung, And from some chamber window hung;

And there they serve a roost for flies Until they ‘re ready to make pies. T

read on my corns, or tell me lies, But don’t pass to me dried-apple pies.

The hostility of the Indians in the early/mid ’60’s, the difficulty in obtaining supplies on a route so remote from civilization, and the numerous perils incident to floods, snows, tornadoes, etc., rendered the “Overland” one of the great enterprises of the century.

Up Next: Operations

Very nice. I may have more to say later.

I can easily see this being a book. Impeccable research.

I wish my history classes had been half this interesting.

I might have studied harder.