Just beyond the Cooper Creek station, the trail leaves the Laramie Plains and heads into rougher and more dangerous territory along the foothills of Elk Mountain. This stretch passes through Fort Halleck and Rattlesnake Pass to enter another stretch of fairly flat land beginning at Pass Creek. Beyond Pass Creek lies the North Platte River crossing. First though is the Rock Creek Station, now known as Arlington. Winters are rough around Arlington. Even today, semis are blown off the road on I-80 which passes within sight of the still-standing Overland stables of Rock Creek.

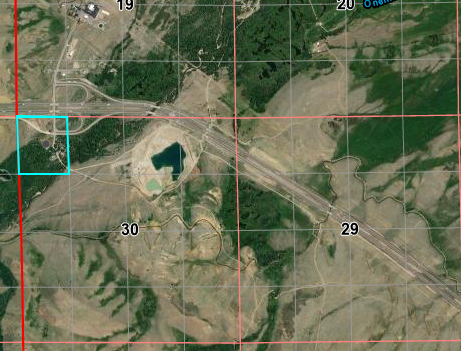

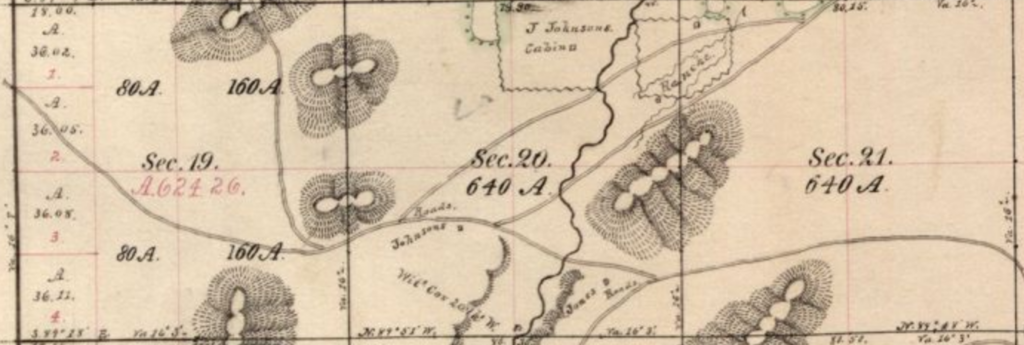

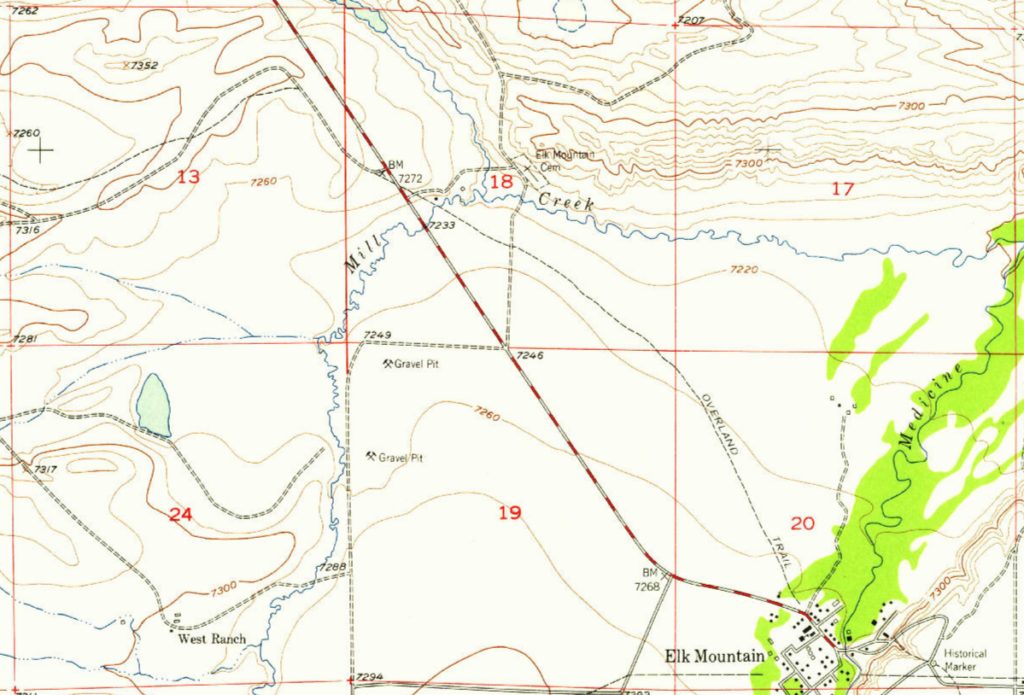

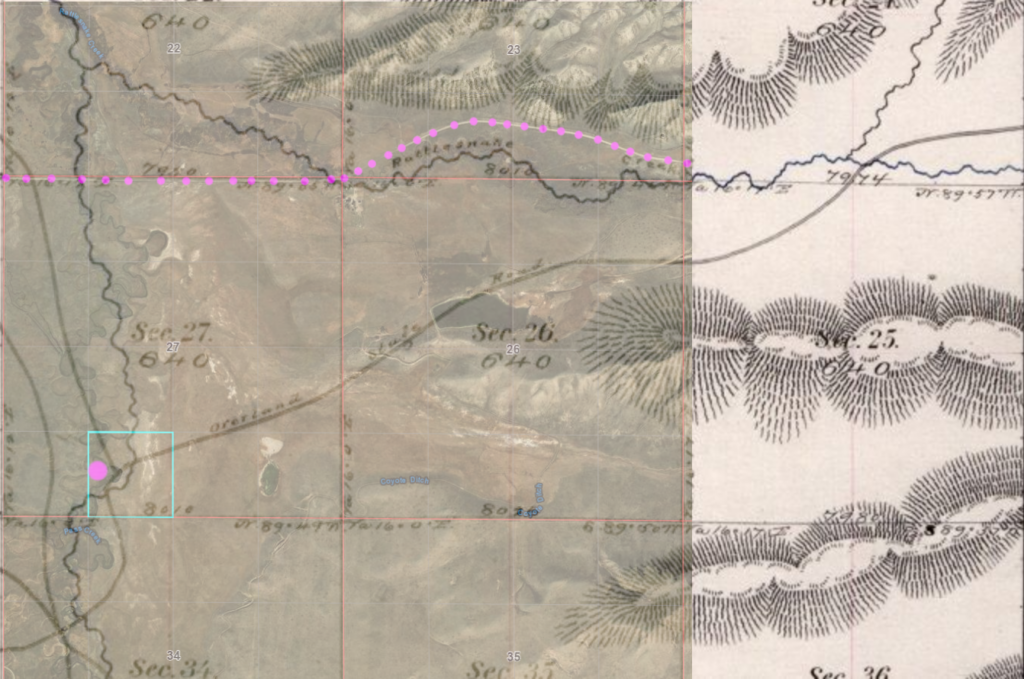

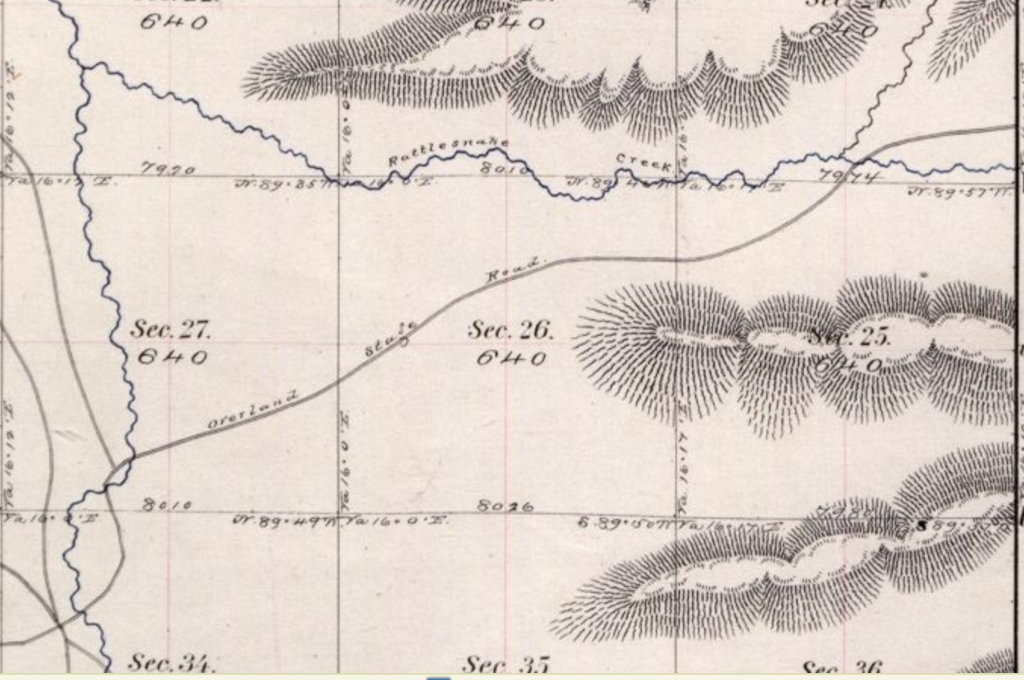

Detailed map: Cooper Creek to Pass Creek

Rock Creek/Arlington

19N78WS30NWNW

41.59523477344985, -106.21031377332736 (the stables)

Equivalent map sections

The Rock Creek Station, not known as Arlington until 1902, was built in 1860. By 1865, Rock Creek was more than just a station, it had become a small town, with not only the station but at least one store and several houses. One of the original buildings still standing on Main Street is a large two-story blockhouse. The lower level housed a blacksmith shop, with the upper floor serving over the years as a bunkhouse, saloon, dance hall, and a school. The creek itself was swift moving and deep; there was a toll bridge which charged 75¢ to cross.

This barn sits right off I-80 and is said to be the original Overland stables for the Rock Creek station.

This location is right off the expressway:

The Rock Creek Station is near where the Fletcher family was attacked by Cheyenne and Arapaho. They killed the mother, wounded the brother and father, and abducted the two little daughters. The on-going attacks on the Rock Creek facilities and wagons in the vicinity were well-documented by diaries and news articles of the time.

Getting close to civilization when signs appear

Elk Mountain

20N80WS20S

41.68692721341098, -106.41302068398345

The Elk Mountain Station was built at the base of Elk Mountain at a crossing of the Medicine Bow River. The station structure was a long log building with stables for livestock on one end, a center section for hay and grain, and living quarters for the employees at the other end. The river banks supported lush foliage, ideal for covering a close approach by Indians. A blockhouse was built nearby for defense against the numerous attacks.

This is from survey adjustments over the years and added much fun to comparing maps of 100 years separation

The building to the right is the Elk Mountain Hotel, built on the site of the station.

This photo was taken in the dry season

The hotel caters to hunters in the area

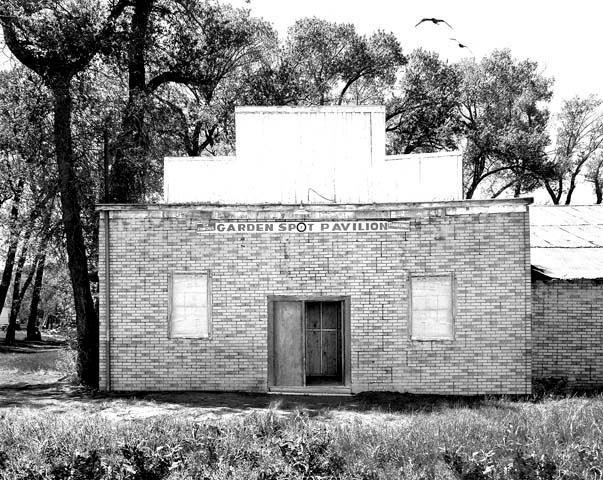

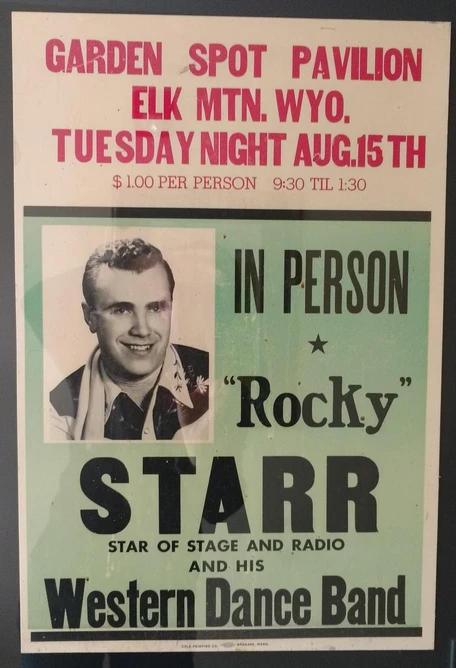

The town itself wasn’t formally organized until 1909 when it served as a base for coal and timber interests in the area. Its claim to fame is the Famous Garden Spot Dance Pavilion. The Garden Spot, with its renowned bouncy dance floor, was originally a livery stable for travellers along the Overland Route. In 1905, the Grand View Hotel (now the Elk Mountain Hotel) was built in the field where the station was located, and in 1920, the nearby livery stable was converted to a dance hall. The unintended consequence of the way the dance floor was constructed – too much space between joists – was the floor bounced. “If you can’t dance, just jump on and ride“.

Until I-80 was constructed in the 1970s, the main route between Denver and Salt Lake was US30. In 1945, the owner of the dance hall convinced many of the big bands to take the 15-mile detour. For 10 years – 1948 to 1958 – many of the Big Bands and others – Louis Armstrong, Lawrence Welk, Hank Thompson, Jim Reeves, Tommy Dorsey, Merle Haggard – played to crowds of 600 – 800 people; the largest for shows by Hank Thompson and Harry James.

A saloon was across the street which led to excessive merriment among the crowd. One night a deputy used his pistol as a club on one of the drunks. The gun discharged and an innocent man was killed. The deputy left town shortly thereafter.

In 1954, the Union Pacific Railroad converted from coal to diesel and the coal mining towns began to die off. Television became popular and dance pavilions became less so. Performers such as Merle Haggard continued to play here into the 60s and 70s but crowds became smaller. The pavilion continued with local parties and weddings but the building was declared unsafe. Both the pavilion and saloon were torn down in the late 90s. I passed through before the buildings were gone, not realizing the significance of the deteriorated structures. The hotel however has been restored and is now a thriving business.

On to Fort Halleck and Pass Creek Station

Fort Halleck

20N81WS17/20

41.699076343006475, -106.52309681545817

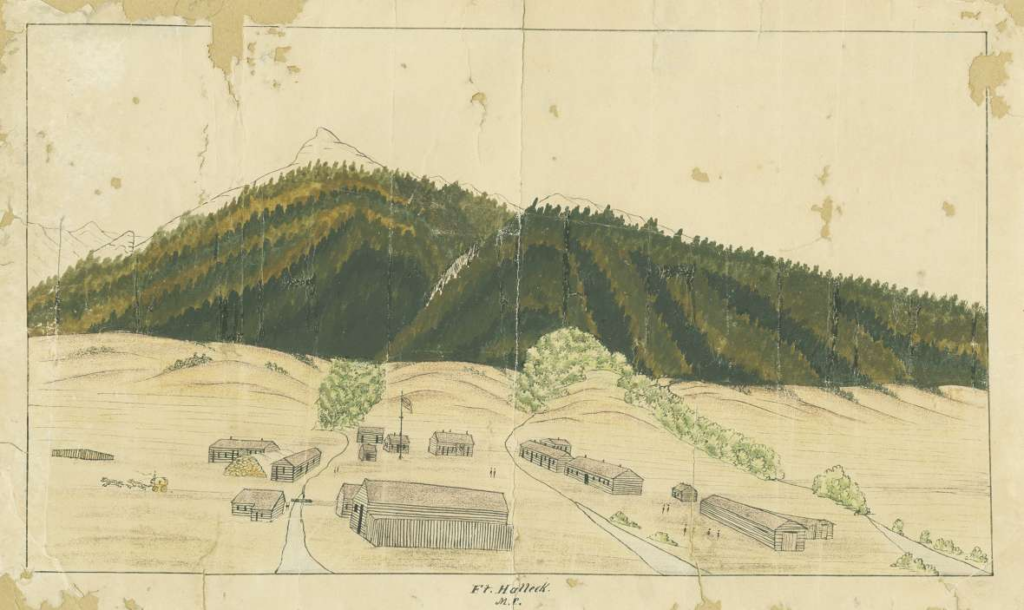

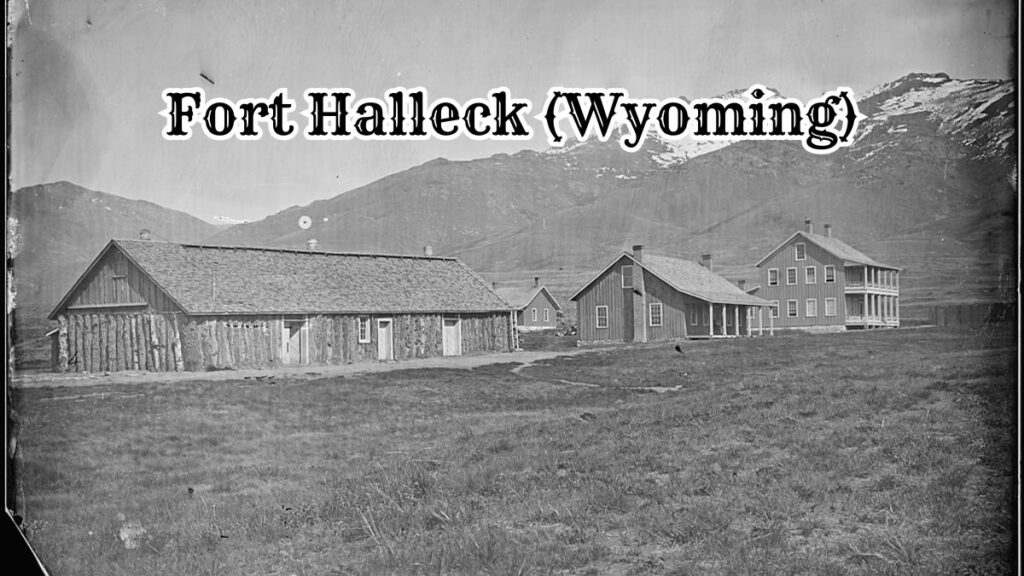

Fort Halleck was named after a Civil War general and was established at the base of Elk Mountain by the 11th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry in 1862 to protect the Overland Trail Stage Route.

Jack Slade spent time managing the Ft Halleck station and sometimes driving the route himself from Virginia Dale. Nothing remains of the post except possibly the blacksmithy; the site is on private property.

The fort was established in 1862 to protect the Overland Trail Stage Line from on-going Indian attacks. The site sits on the north face of Elk Mountain among tall grass meadows at an elevation of 7300 feet. There was a nearby spring for water and close forests to supply wood for building, cooking, and heat. Meat was provided by large herds of elk, deer and antelope. The fort itself was large with stables capable of holding 200 horses, storehouses, two sets of company quarters, officers’ quarters, a store, bake house, hospital, and jail.

The post surgeon kept very detailed records of the emigrants passing through the Fort Halleck station. In 1864 he recorded that there were over 4200 emigrant wagons, with a staggering number of 17,584 emigrants and an even more astonishing total of over 50,000 animals traveling the Overland Trail.

One traveller, Franklin Adams, kept a diary of his trip on the Overland Trail in 1865. He mentions that the soldiers from the 11th Ohio Cavalry stationed at Fort Halleck were paid $16.00 per month to fight the Indians. The stretch of trail from Fort Halleck to Sulpher Springs to the west was considered to be one of the most dangerous sections due to Indian attacks.

[A good book describing a soldiers life in eastern Wyoming during this period is “Tending the Talking Wire“,

the letters of Hervey Johnson of the 11th Ohio Cavalry, edited by William Unrau]

It is told that on one occasion when Jack Slade was in charge of the Mountain Division of the Overland Trail, he apparently went into the fort store and used the canned goods on the shelf for target practice. The second time he caused trouble at the fort, the commanding officer arrested him and refused to release him until Ben Holladay promised that he would be fired. Holladay kept his word and Jack was fired soon after.

The fort was abandoned in 1866, lasting just four years after being established, and by the next year it was described as “the most dreary place on the entire route“. It appears the blacksmith shop is the only remaining evidence of the fort’s existence. There is a marker erected in 1914 at the site of the fort cemetery.

After leaving the fort, the route went through Rattlesnake Pass; the modern road more or less follows the same path.

Not much room for the Overland Trail and “modern” road to vary much

Rough country to live in

Coming off Rattlesnake Pass heading west

Pass Creek Station

20N83WS27SWSE

41.67191400221689, -106.72279034459972

The Pass Creek Station was located at the west side entrance to Rattlesnake Canyon. This was a favorite place for Indians to hide and ambush. Nothing remains of the station. Aerial views show the creek has changed course quite often in the days since the stage making determination of the exact location essentially impossible. The 1873 map shows a junction at one feasible location which is marked; also shows another slightly south.

Modern rattlesnake Pass Rd in MAG dots

probable station location within CYN square

low water this time of year

Next: past the North Platte crossing to the Bridger Pass station