I took some time to explore what I could of the old route between the last station in Nebraska (near the I-80/I-76 split), down into Colorado, and on across Wyoming to the mouth of Echo Canyon not far into Utah (the I-80/I-84 split). There is not much left except along the Bitter Creek Division in Wyoming … and not much there either. What’s left is likely because that segment is well off the beaten path and while mostly not necessary in good weather, 4-wheel drive and “I’m stuck” equipment is highly recommended. Myself? I wouldn’t dream of going out there in a car … now, although when I was much younger, I wouldn’t have hesitated.

Significant remains with easy access include the original Virginia Dale station – probably the most complete but is on private land. i understand tours may be available with special permission. The Point-of-Rocks (Almond) Station still exists in arrested ruins just off I-80 exit 130. Granger Station exists not far off US30 a few miles north of I-80 but is fenced off, and the Fort Bridger site is a state park reconstruction. The others – if existing at all – are sites in a field or piles of rubble. A few pieces of walls still stand along the Bitter Creek section.

With the mining activity in Wyoming since, perhaps much of what I discovered even along Bitter Creek has since disappeared. Much of the route is on private land … that wasn’t me anyone saw crossing that fence.

I explored the route from two directions at different times: East from the junction of I-76 and I-80 to Virginia Dale, Colorado (mostly easy access and not much to see) and west from Echo, Utah back to Virginia Dale with special attention to the Bitter Creek division in Wyoming. There was not much to explore along the South Platte and access was blocked between Wyoming highways 130 and 785 – encompassing the North Platte crossing (where I almost got into a bit of trouble) along with the stations Sage Creek, Sulphur Springs, and Washakie. Access to Pine Grove is questionable – the location is redacted in most documents, leaving only the Bridger Pass Station along a publicly accessible road. However, other than Duck Lake – now under an oil field, the stations along the Bitter Creek route are – or were – accessible at the time I spent out that way.

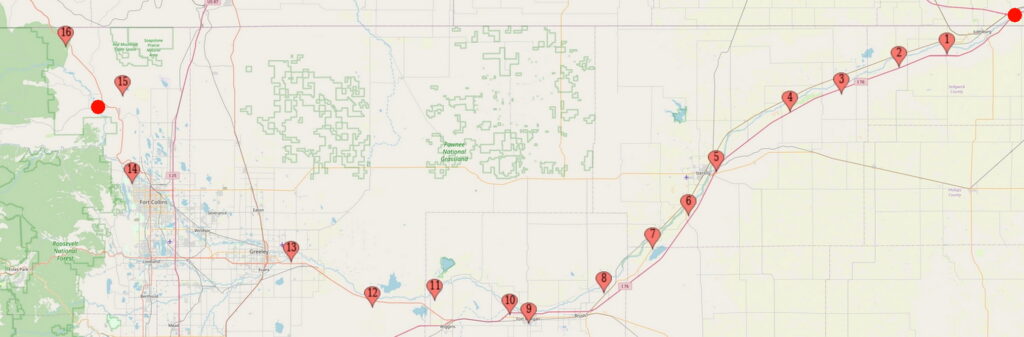

Route Overview

Working westward:

From just NE of the upper NE corner of Colorado at the I-80/I-76 junction in Nebraska – South Platte Station – to modern Wiggins, the route lies between I-76 and the river just to the north; at Ft Morgan, directly under I-76. From Wiggins to Greeley (Latham), the route closely follows US34; crossing the South Platte (and leaving it) at or very near the present US34BR bridge into Greeley. From Greeley to Ft Collins, the route roughly follows the railroad along the Cache la Poudre River. From Ft Collins to Virginia Dale (and north into Wyoming), the route closely follows US287 – although later, the route shifted to the other side of the ridge east of US287 for part of that segment.

After 1864, the main route was diverted to Denver from Latham, continuing to follow the South Platte – roughly US85. Later, the route to Denver split off near Ft Morgan (there were several junctions) where I-76 more or less follows the trail. From Denver, the new main route headed north, pretty much following US36, then a bit west of US287 to LaPorte, re-joining the original route.

Sections of the original trail are now county roads, sections are on private land, sections have long since disappeared into flood plains and drifting sand. Even the earliest maps – produced after the time of the Overland – don’t always show the road and rarely show station locations (they were abandoned by the time the surveys were conducted), even if only five years later. Latham – once a major supply and shipping terminal – itself has disappeared into open fields and farmland, faded away to the point where few know (or care) where it was; Greeley to the north-east and on the other side of the river has taken over in importance and population.

From Latham – originally near the confluence of the South Platte and Cache La Poudre rivers until the floods of 1864 – the trail splits. In later days, the main trail cut south to Denver continuing to follow the South Platte, then back north to rejoin the original trail near what became Ft Collins. The original route – Denver wasn’t truly a town yet – headed NW from Latham following the Cache la Poudre River, passing through the area that eventually became downtown Greeley (founded in 1869 as “The Union Colony” – an experimental utopian farming community “based on temperance, religion, agriculture, education and family values.”) and roughly follows the present railroad route along the la Poudre through Windsor (a late-comer – 1882 – which was built directly on the trail) through Ft Collins (not even the fort existed at the beginning), then upriver to LaPorte.

From LaPorte – a major home station, US287 somewhat follows route north past Virginia Dale to the Willow Springs station near Tie Siding, Wyoming where the trail heads straight NW across the Laramie Plains; joining I-80 where it enters the hills west of Laramie just east of Arlington. Not far west of US287 in LaPorte, Overland Drive passes directly past the site of the station (burned down in 1928) and further north just shy of the Wyoming border, US287 passes near Virginia Dale – often advertised as the only remaining station in Colorado. (Perhaps as a home station; a later swing station still exists in Windsor – but Virginia Dale is the most famous.)

One should keep in mind most of these town names are for convenience of location; few if any of these towns existed except possibly as stations in the day of the Overland. The home stations were the big settlements of the time and most of the towns mentioned didn’t exist until the railroad came through in 1868/69 … and the railroad’s existence ended the Overland and Wells-Fargo stage lines.

Arlington, Wyoming is purported to have standing an original Overland stable and blockhouse. If true, the stable is just off an I-80 exit and easily visible from the highway. Not that anyone would notice anything special about the building.

From Arlington (then known as Rock Creek) to Elk Mountain – the Elk Mountain Hotel sits on the stage station site along the Medicine Bow river – the trail follows due west, south of I-80. The road from Elk Mountain to Ft Bridger was originally surveyed as a military road in the mid-1850s; the stage line used a path already in existence. The second overland telegraph also followed this road, often using the home stations as telegraph offices.

Portions of this section of the route are plowed under for agriculture, impassable, or on private land – such as the segment passing through the site of Ft Halleck. Past Ft Halleck, the closed section rejoins the original (and public) route, now Rattlesnake Pass Road (which is a public road west of Elk Mountain and north of the site of Ft Halleck). There might still be public access to the Ft Halleck cemetery site but I didn’t check it out. Private land and fences abound in this area.

Coming down off Rattlesnake Pass, the trail heads west across the sage and sand covered desert, crossing the North Platte River about 15 miles south of I-80. The trail continues west (inaccessible to the public), crossing the continental divide at Bridgers Pass (which is accessible), then down along Muddy Creek south of Red Desert, following along Bitter Creek to Point of Rocks (aka Almond Station) – another existing station immediately south of an I-80 exit.

The section from Point of Rocks to Green River closely follows I-80 – more correctly, the railroad – then to Granger, still along the railroad, where the Overland Trail re-joined the California Trail. From there to Ft Bridger, across a different Muddy Creek to the site of Bear City and on to the head of Echo Canyon near Wahsatch (an I-80 exit) in Utah, through the canyon to where I-84 splits off I-80 and I end this journey. From Point of Rocks to Granger, much of the trail became one of the versions of the Lincoln Highway.

In May 1859, the mail contract between Julesburg and Denver was purchased by Jones, Russell & Co. The company built stage stations at appropriate distances along the trail and entrepreneurs immediately built ranches and trading posts along the line to serve the “pilgrims.” These posts were often called “road ranches” or just “ranches”. The occupants of all these posts were mostly squatters and the posts often informally changed hands from 1859 until the area was surveyed in 1867-1872. “Ownership” records were not kept until at least 1861 if then.

There were few neighbors for those at the stations – each being twelve to fifteen miles apart. Entertainment could take the form of dances which frequently took place at the home stations. It was not unusual for the women to ride on horseback or take the stage to travel some ten or thirty miles, dance away the greater part of the night, then ride back home. Some rode as far as fifty miles each way; neighbors and entertainment both being scarce.

The entire South Platte River route was part of Nebraska Territory when the route was formed in 1859 (the border between Nebraska and Kansas Territories followed the current border at 40N latitude west to the mountains. Denver – such as it was at that time – was in Kansas Territory, most of the stage road in Nebraska – the border being just south of present day Boulder, strangely enough, along Baseline Road). Later that year, the route was in the informal Jefferson Territory until 1861 when the Colorado Territory was formed. Golden, not Denver, was the capital at that time until 1867. Formal land transfer records were not kept during this time until Weld County was formed within the Colorado Territory. St. Vrain was the original Weld County seat; later moved to Latham, eventually to Greeley.

For the first several years, relations with the Indians were fairly peaceful; however, the Sand Creek incident in late 1864 changed that. Retaliation by the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux led to wide-spread killing and the destruction of most stations and road ranches along the Overland Trail in early 1865 to the point of closing the trail for a period of time.

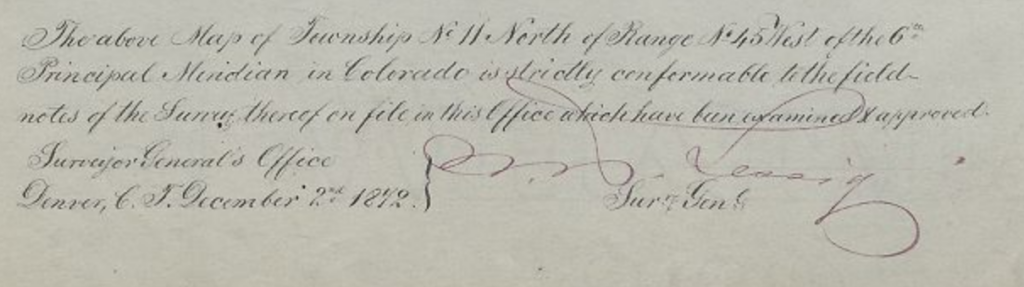

Some stations and road ranches never were rebuilt; when official surveys were completed between 1867 and 1872, the remnants of burned-out stations or ranches were not considered worthy of mention or placement on respective land plats. As a result, the exact locations of most stations and road ranches were not recorded leading to some uncertainty of their actual location.

But that’s OK – I’ve pinpointed the locations for you … with more details in coming adventures 🙂

In any event, the trip overland was considered a hazardous one, across the mighty expanse of country, a portion of it beset by savages, and known upwards of half a century ago as the “Great American Desert.”

A note on maps. For all intents and purposes, there were none at the time of stagecoach operations. Some military surveys, proposed railroad routes, mining claims, some local sketches, many of which have been lost over the years. Properly conducted surveying efforts did not start until after the stage line was abandoned by both the Overland Stage and Wells-Fargo companies and the railroad having been in place for a year or more. Much development occurred within a few years after the time of the stagecoach and while the stage road itself shows on most maps – other roads built after the time of the stagecoach are included and can cause confusion as to which set of faint tracks was the actual Overland Trail. On those maps, it is rare that the now abandoned and/or burned out station locations are marked except where those stations that were or became ranches … but not always even then.

Next up: Jack Slade/Julesburg/Fort Sedgwick