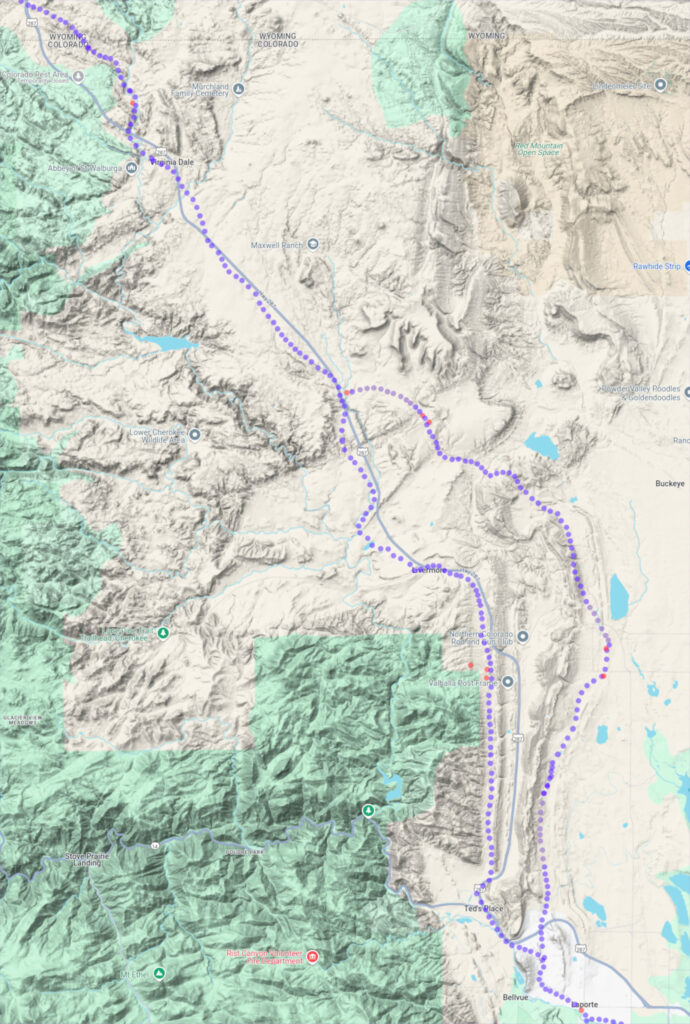

LaPorte to Virginia Dale

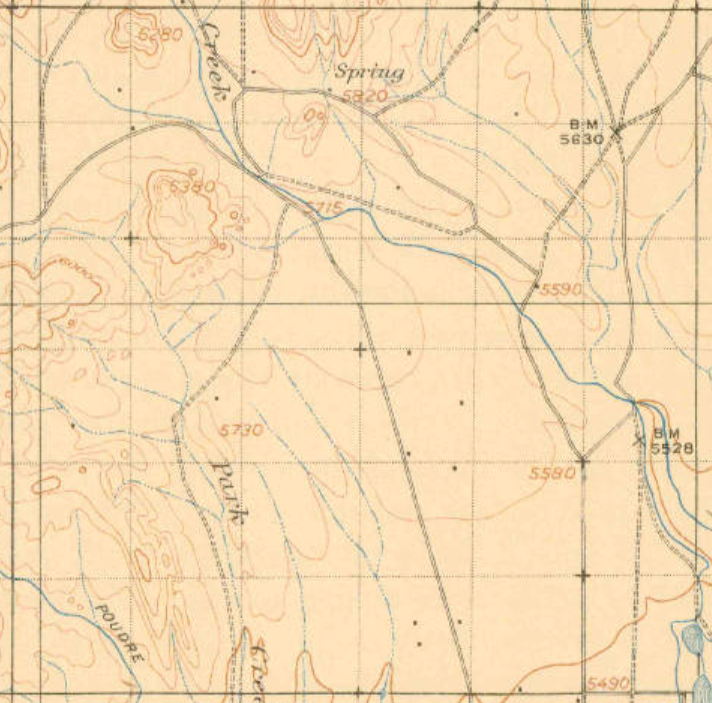

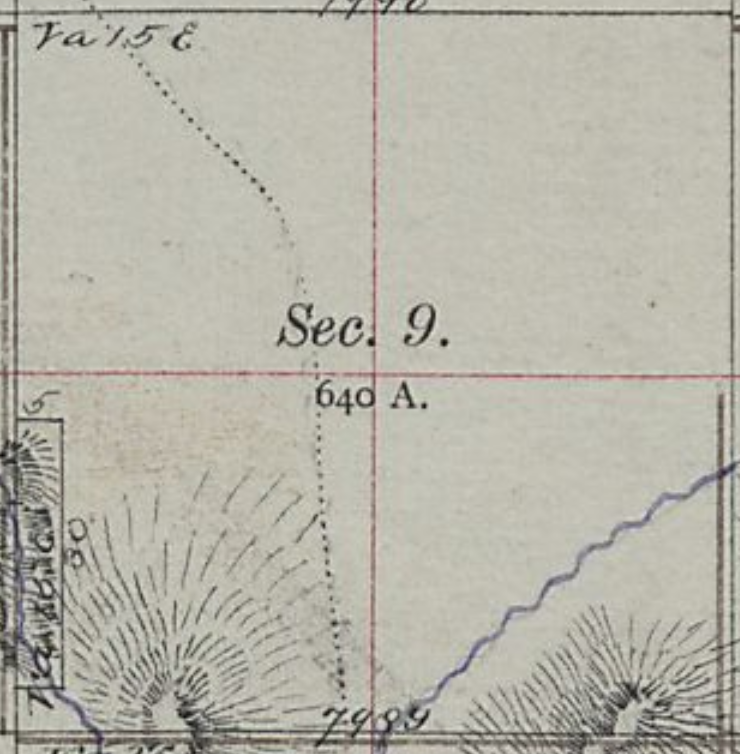

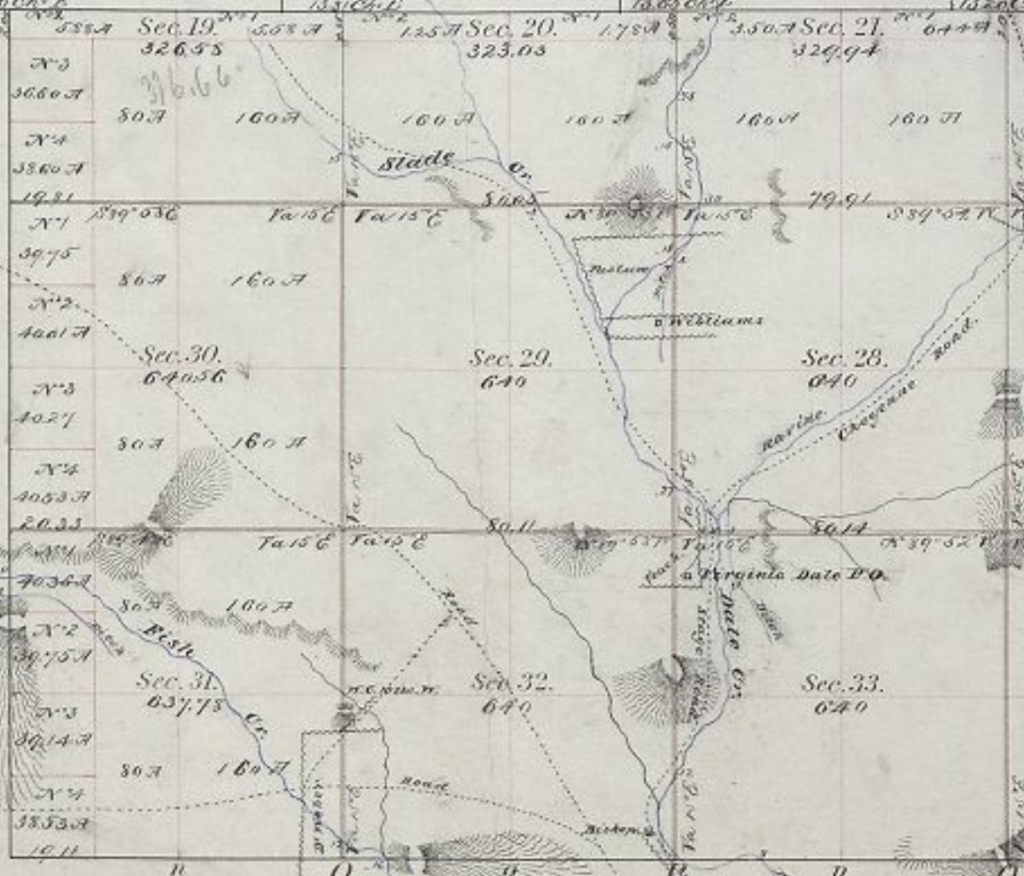

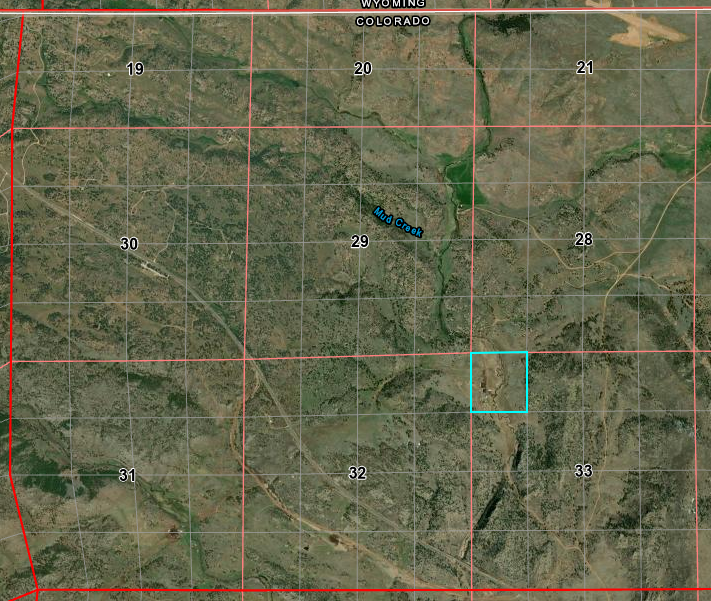

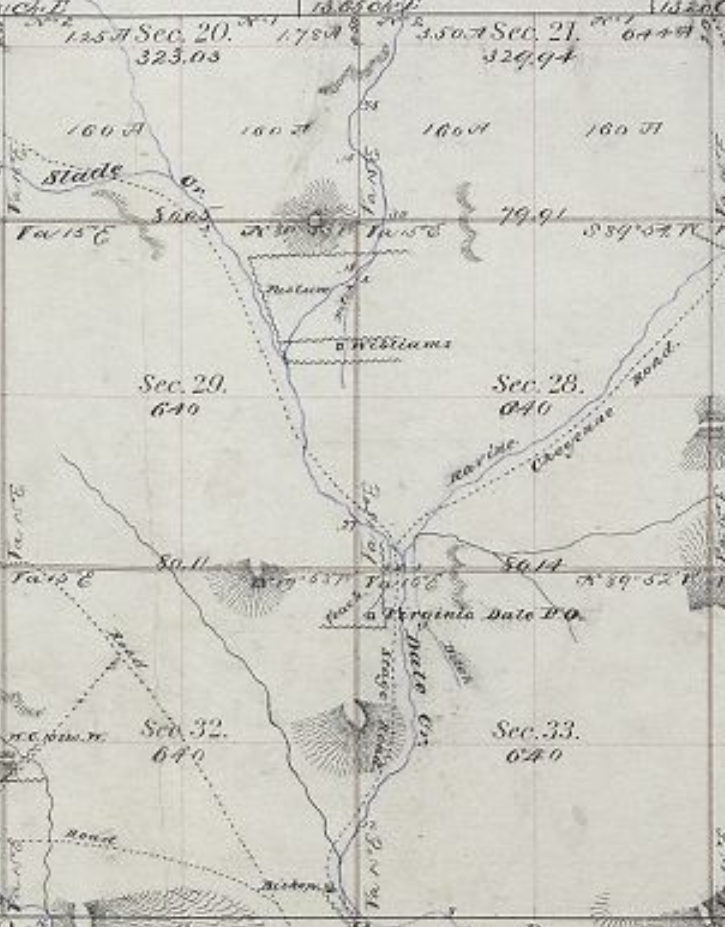

This segment of the route was by far the most difficult to track down. The route changed several times; townships having been surveyed well after stage operations, and the development of the area after the mid-1860s did not aid the search. That and in several places, the maps were either incomplete, showed many roads with ambiguous labeling, or in some places, features did not line up with adjacent townships. It also seems this is an area where survey corrections were made – the newer survey lines have “jogs” that cause the old maps to be out of alignment when compared to known and fixed features – the location of the Virginia Dale structures that still exist for example.

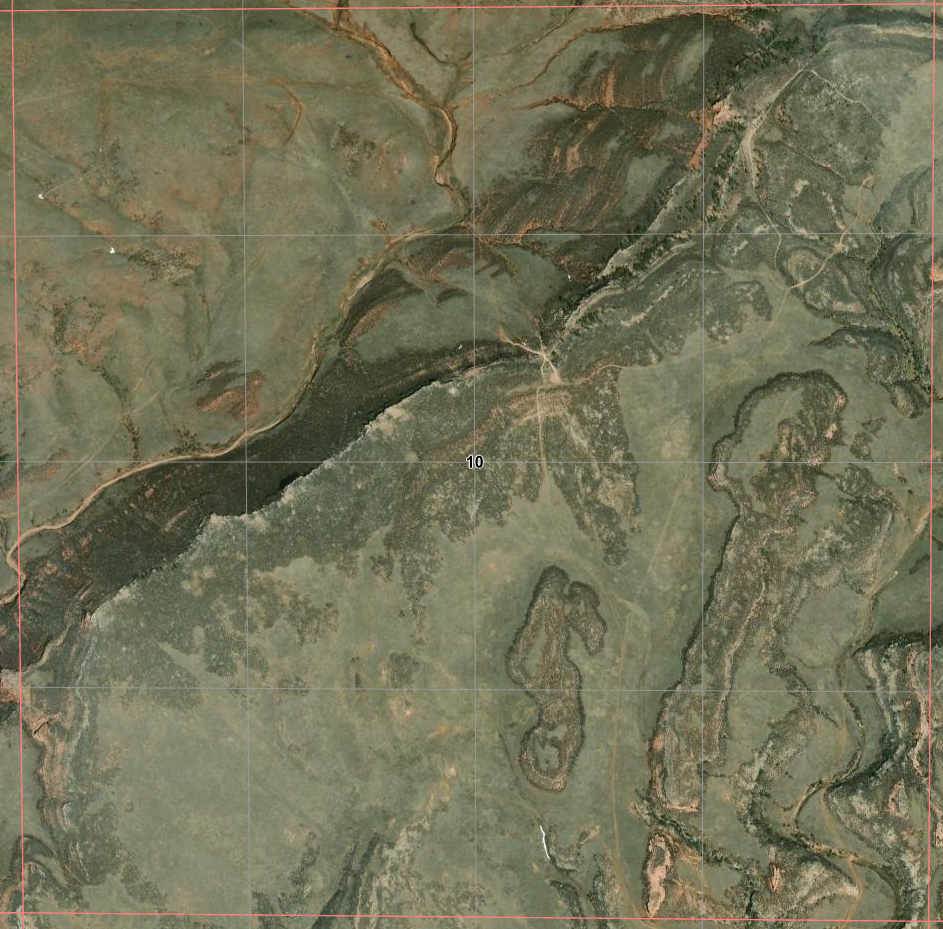

Where possible, descriptions of the route written by travellers of the time were used as aids for tracing the actual road (for example, “the Horseshoe” and “Devil’s Washboard”are prominently mentioned yet no map shows a route through these features. The aerial maps helped – the area is even now remote enough that traces of the road and some structure remnants remain; sufficient to align the old with the new.

One can not discount the idea that the old maps are wrong – though for the most part they align nicely with satellite images.

LaPorte to Wyoming Border – Primary Routes

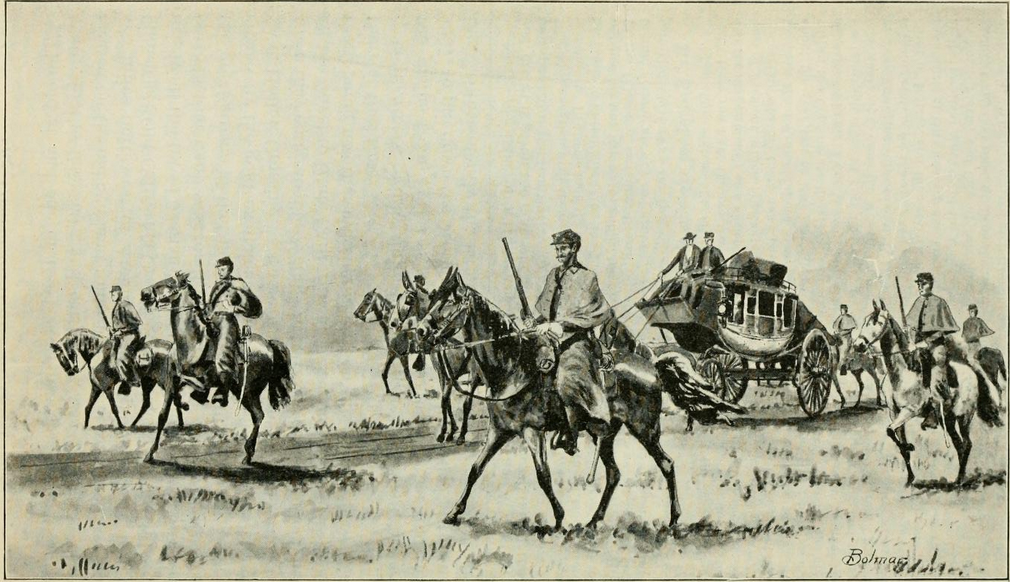

Much trouble was experienced with the Indians in the summer of 1865 along the stage route west of Camp Collins. In July most of the stock was stampeded, seriously delaying the running of stages and transmission of the mail. Tons of mail matter destined for Salt Lake, Montana, Nevada and the Pacific coast accordingly accumulated at Fort Halleck [Wyoming], where as many as half a dozen large Government wagon-loads of it were transported west as far as Green river, under an escort of cavalry. The long delay in the stopping of the mail was practically a repetition of the scenes that had occurred along the Platte during the summer and fall of 1864, when the Indians for six weeks had possession of several hundred miles of the overland line.

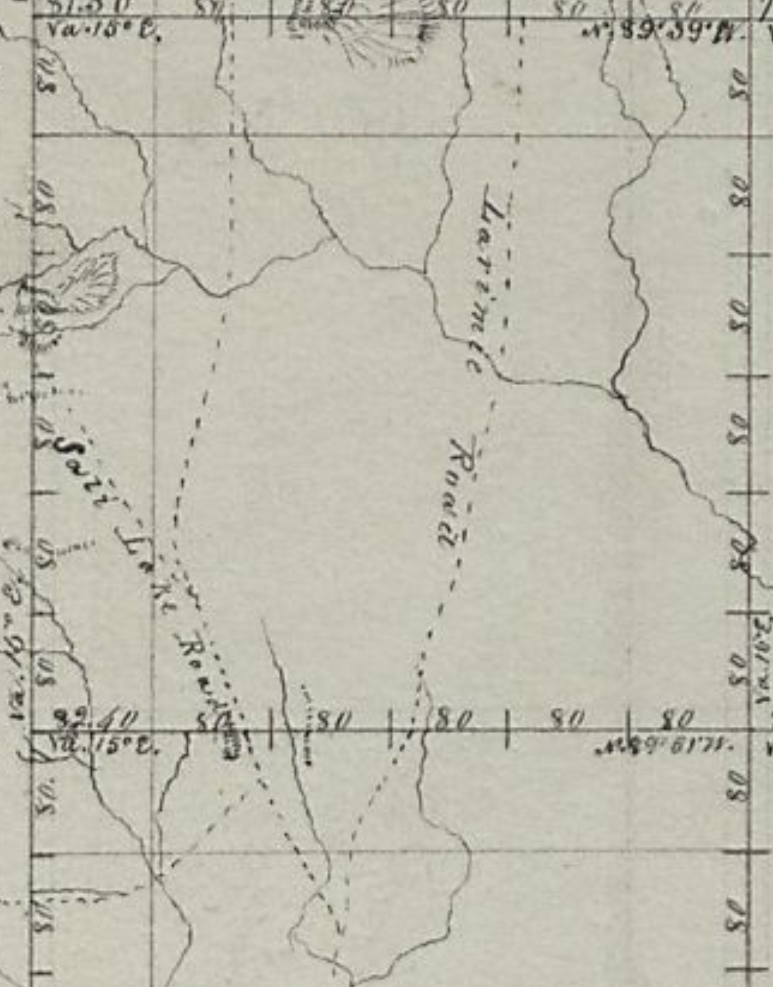

Before the stage routes developed and the gold rush led prospectors to explore – and in some cases, settle, the Cherokee Trail was the only route skirting north through the foothills up to Wyoming. The Overland Route followed this trail along this segment.

LaPorte

(Colona until 1862 – HQ Mtn Div Overland Stage)

40.621405361511464, -105.13968091975305

8N68WS32NE

LaPorte is one of two stations along the trail that developed into a town existing today; Ft Morgan and being the other. It is the only “known” station location along the trail until Virginia Dale although possible foundations are visible at other stations.

Trappers built cabins along the Cache la Poudre River as early as 1828 when a band of mountain-men – hunters and trappers – made the LaPorte region a headquarters for related operations – it’s a quite pleasant region. The settlement grew, including lodges of Arapaho Indians who also settled along the river.

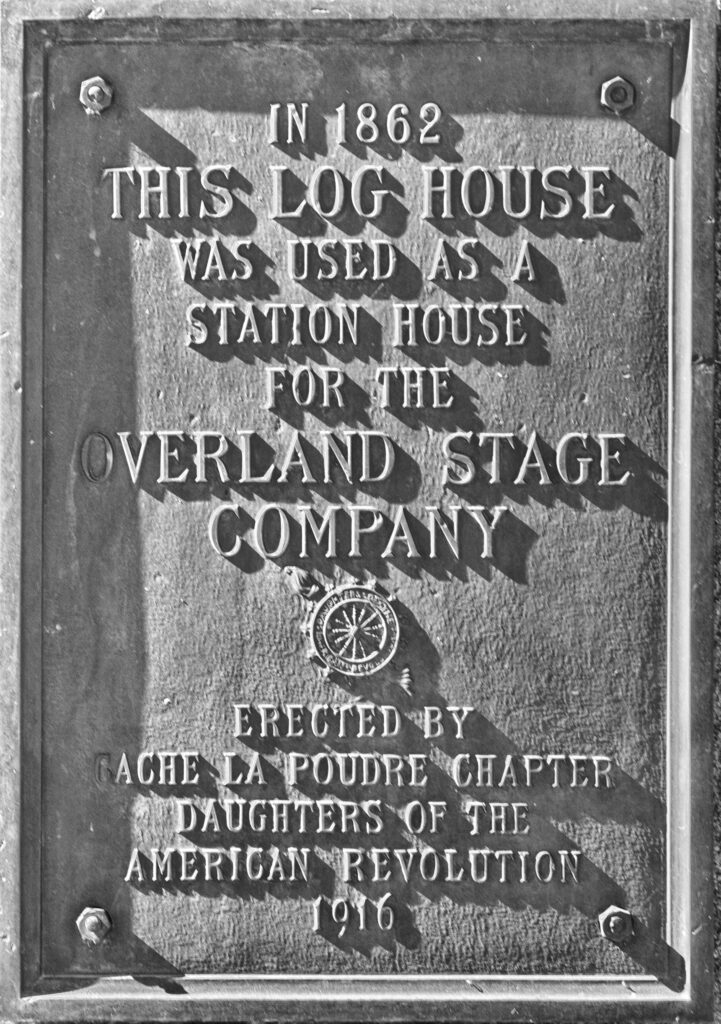

A town was organized in 1860 as Colona with fifty or so log dwellings constructed along the Cache la Poudre River; by 1861 it was the county seat of Larimer County. The town changed its name to LaPorte in 1862 when it was named the headquarters of the Mountain Division of the Overland Stage line. The station was erected right along the river – a marker at the location is on the present Overland Trail Road crosses the river. The stationed burned down in the 1920s.

LaPorte was also the original location of Camp Collins until a flood almost wiped out the camp, causing the commander to relocate to what is now Fort Collins.

Mrs Taylor, wife of the first stationmaster, was a “good cook” and “gracious hostess”, and as described by one diarist, knowing “what to do with beans and dried apples.” It is claimed that General Grant stayed at the station in 1868.

Fare from Denver to LaPorte was $20.00. While the original trail was on the north side of the river – as was the station – the trail from Denver (slightly west of today’s US287) crossed more or less at the site of the present Overland Road bridge. The first bridge was built as a toll bridge and during the rush west, daily traffic could be heavy. The toll ranged from $.50 to $8.00 depending on what was crossing. The bridge washed out by the flood of 1864 and a ferry was rigged up to replace it. Eventually, the county built another bridge.

With wagon trains and stagecoaches passing daily and having status as a division headquarters, it didn’t take long for LaPorte to become a busy business and supply center for passers-by. The settlement had four saloons, a brewery, a butcher shop, two blacksmith shops, a general store and a hotel. After the route was changed to pass through Denver, LaPorte became the most important settlement north of Denver, having the stage home station and county court house.

A company of infantry stationed at LaPorte acted as an escort for the Overland Stage on the trail to Virginia Dale. After the flood of 1864, the camp was covered with water, and Col. Collins decided to move the army camp to Fort Collins in August.

The terrain from the east – even far east of Julesburg – was mostly level, following the Platte River plain. After LaPorte, the mountainous territory began.

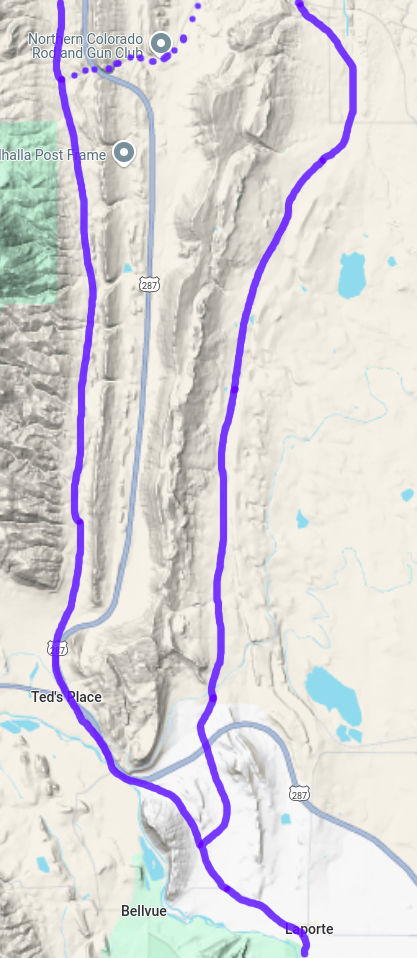

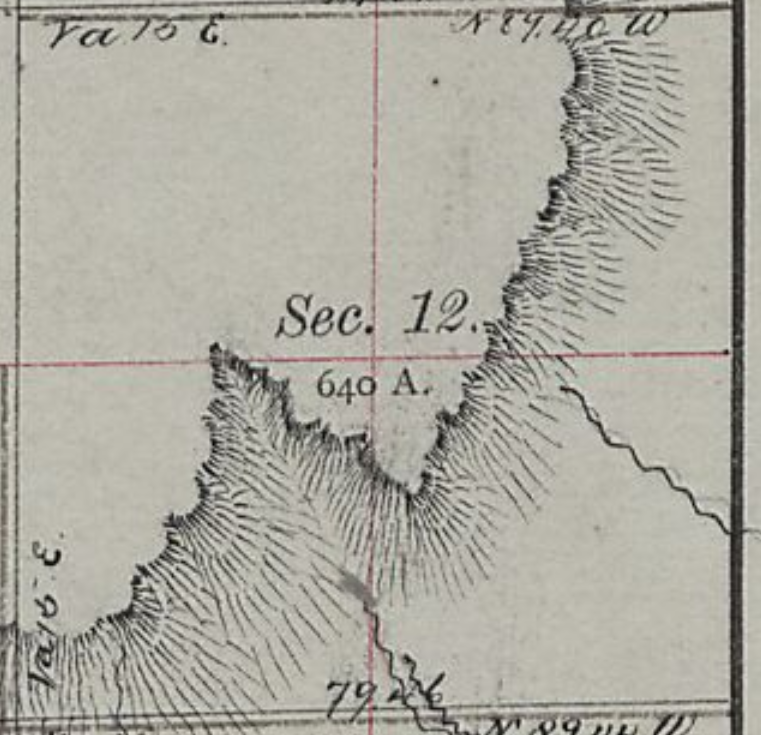

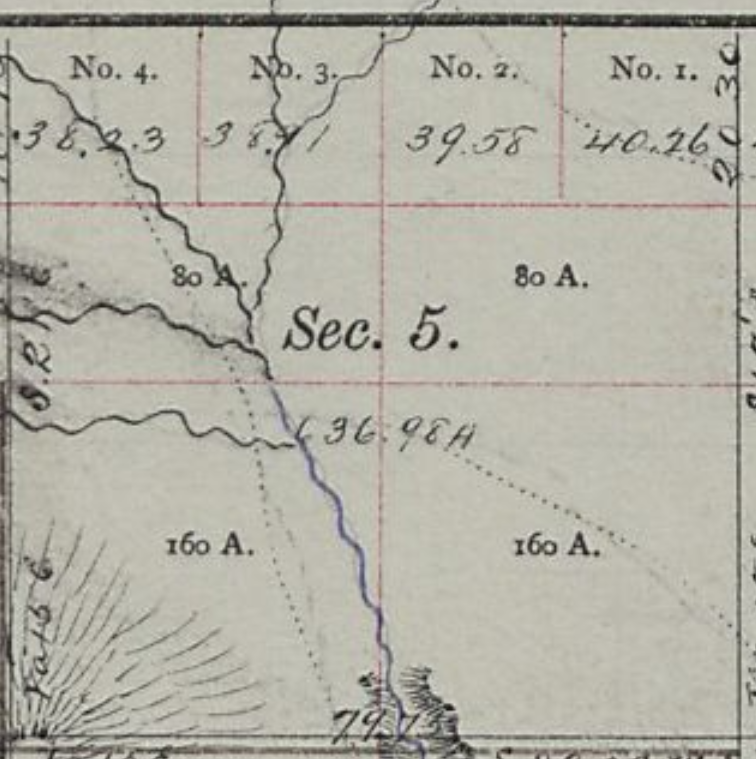

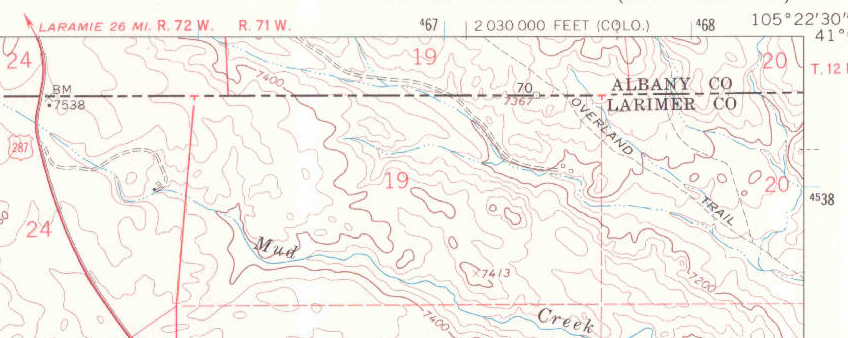

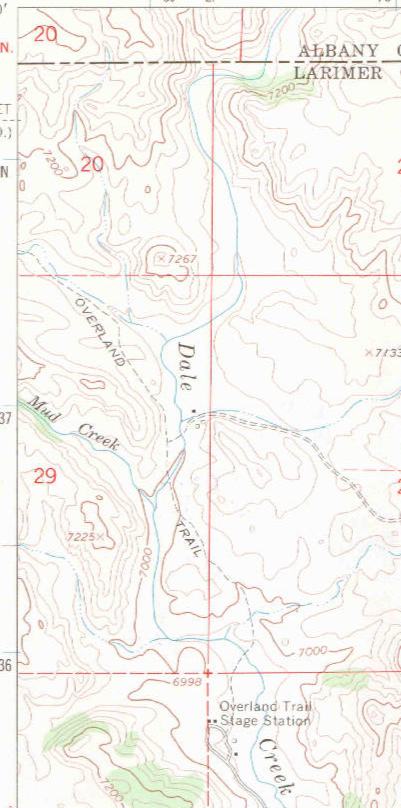

From the terrain map to the left, the narrow NS valleys dictated the stage route. LaPorte itself is now off the main highway route, but today’s secondary road heading NW out of LaPorte is still used for local traffic. The first stage route headed north along the valley west of the modern highway.

The modern and stage routes criss-crossed at Owl Canyon – the jog in US287 at the top of the map. There was a stage station just west of the canyon; a new station was constructed just east with the new stage route then heading north along Park Creek. Several segments of the trail are still in use as ranch roads.

The “main” road moved around as development came and went. Tracking down a specific route at a specific time is not straightforward. The oldest known maps are newer than the Overland Stage operation. By the late 1870s (the survey map around Livermore is dated 1878), there were many roads leading to ranches and mining prospects.

This was Jack Slade’s “home” territory; he was still a division superintendent and the last station in Colorado – Virginia Dale – was named for his wife

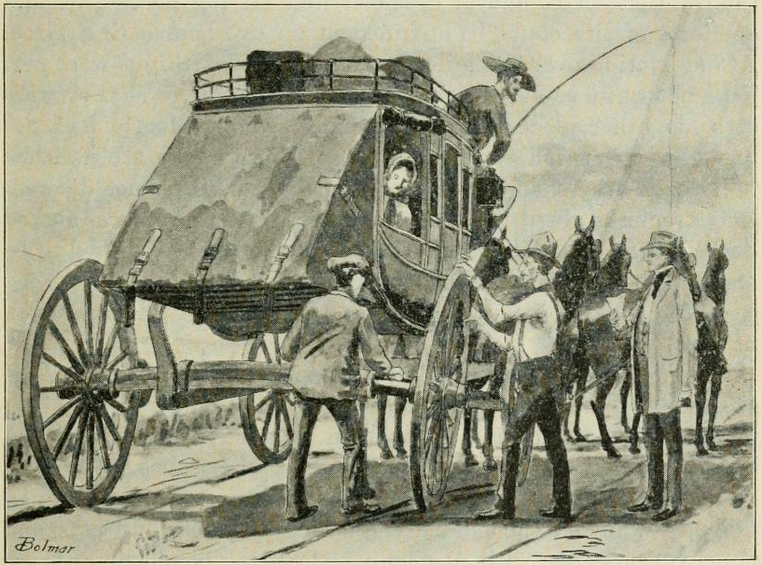

“One pitch-dark night the stage was started from Laporte with Slade and a lot of employees aboard in the convulsions of a ‘booze,’ and one unfortunate passenger. Six wild mustangs were brought out and hitched to the stage, requiring a hostler to each until the driver gathered up his lines. When they were thrown loose the coach dashed off like a limited whirlwind, the wild, drunken Jehu, in mad delight, keeping up a constant crack, crack, with his ‘ snake ‘ whip. The stage traveled for a time on the two off wheels, then lurched over and traveled on the other two by way of variety.

The passenger had a dim suspicion that this was the wild West, but never having seen anything of the kind before, and, being in a sort of tremor, was unable to decide clearly. Slade and his gang whooped and yelled like demons. Fortunately the passenger had taken the precaution before starting to secure an outside seat. The only way in which he was enabled to prevent the complete wreck of stage, necks and everything valuable was finally by an earnest threat that he would report the whole affair to the company.

Slade and some of his men went on a tear on another occasion, when they paid the Laporte grocer a visit, threw pickles, cheese, vinegar, sugar and coal-oil in a heap on the floor, rolled the grocer in the mess, and then hauled him up on the Laramie plains, and dumped him out, to find his way home to the best of his ability. It was only a specimen of the horse-play in which they frequently indulged.“

We set out from this place [LaPorte] through the plains, and hills. We succeeded well, from 15 to 20 miles a day, for some time until we got within some 40 to 50 miles of the North Fork of the Platte, when the hills became worse and we had to detain more time hunting out the route and working it.

Bonner Springs

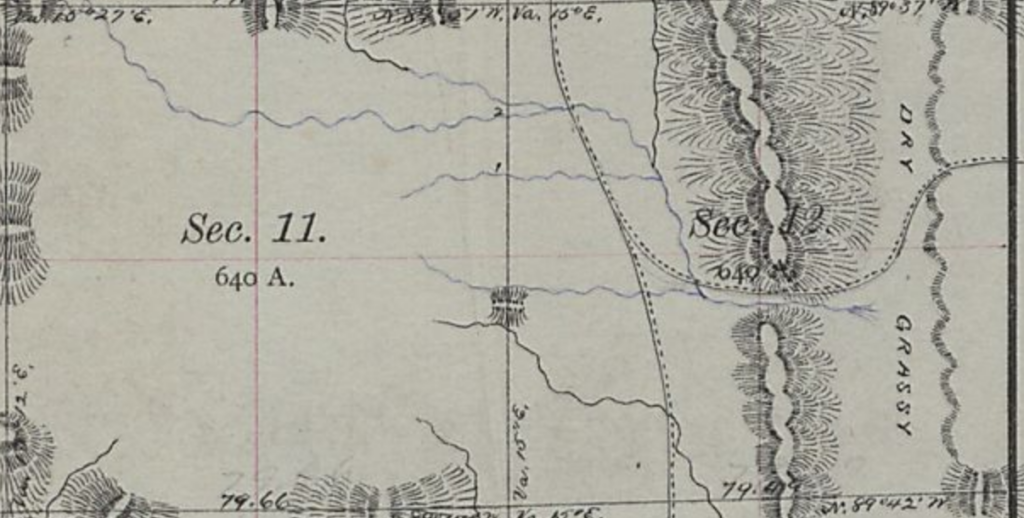

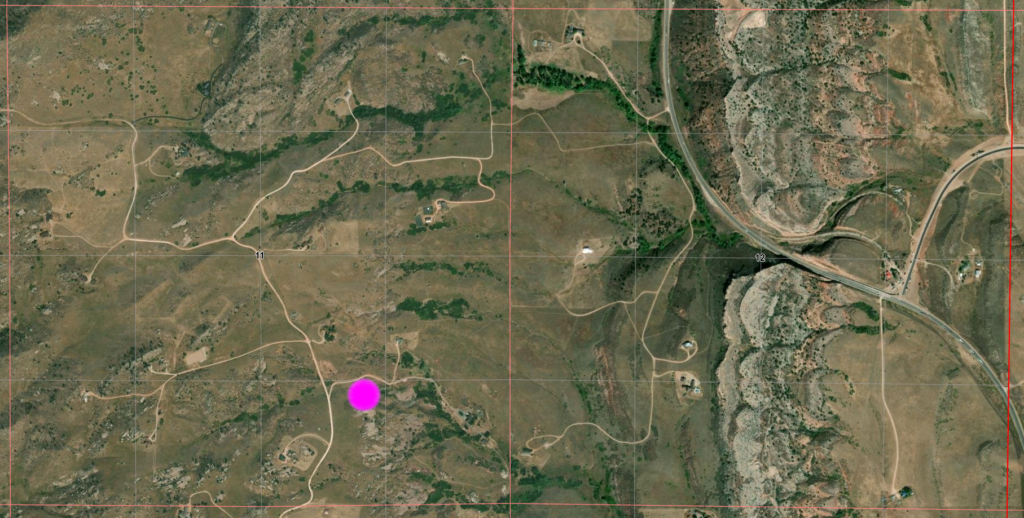

9N70WS11SESW

40.758595867977164, -105.19687090088713

40.75337296728025, -105.1862148981457 – Possible station remnants

The Bonner Springs Station was a swing station located near some springs about 10 miles north of LaPorte. Originally called “Boner Station” by Jack Slade (superintendent of the station) after a Dr. Boner who took care of him after being shot by Beni in Julesburg. The name was changed later by travellers from Bonner Springs, KS. The nearby springs made it a favorable camping spot. After the stage line abandoned the station, it became a hideout for the Musgrove Gang who made a habit of stealing government horses.

Musgrove was eventually caught and brought to Denver, Colorado, where he was taken by a group of citizens and hung from the Larimer Street Bridge on November 26, 1868.

Possible evidence of foundation?

The road was a bit east of this point

The route through Bonner Springs was moved east in 1863 and the station was abandoned. There was reported to be a child’s grave dated 1864 just south of the station but the headstone has disappeared and there are now several houses in the area. Nothing remains of the station but the apparent remains of foundations near the spring are evident. There is a modern marker at the grave site however.

40.75337296728025, -105.1862148981457

US 287 follows the original stage trail north from this point. Remnants of the 1877 roads are still evident

I get lost in the weeds so to speak in what follows … exploring the unexplorable; tracking rumors and hidden remnants.

Perhaps one of the most interesting, unchanged, and inaccessible areas of the route in Colorado is that section between Park Station and Virginia Dale. I doubt a truck could get deep into the territory – even if it weren’t blocked off by private lands. I’d love to take a dirt bike up into that mess of a landscape and spend a week exploring … but some places look to be accessible only by foot or horse.

This section was some of the roughest trail along the route.

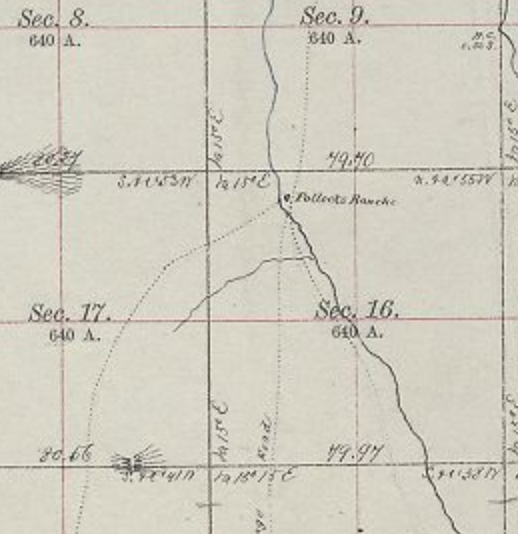

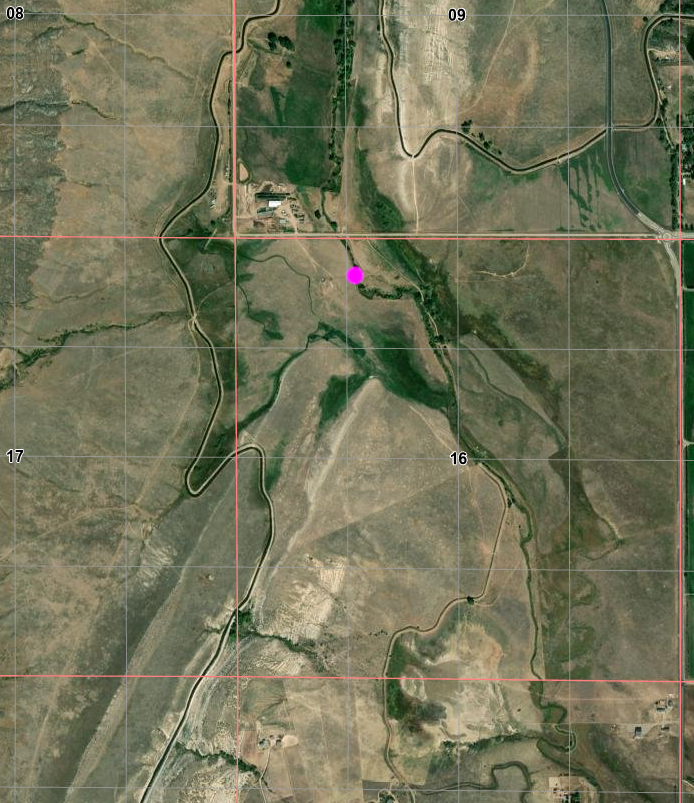

Park Creek

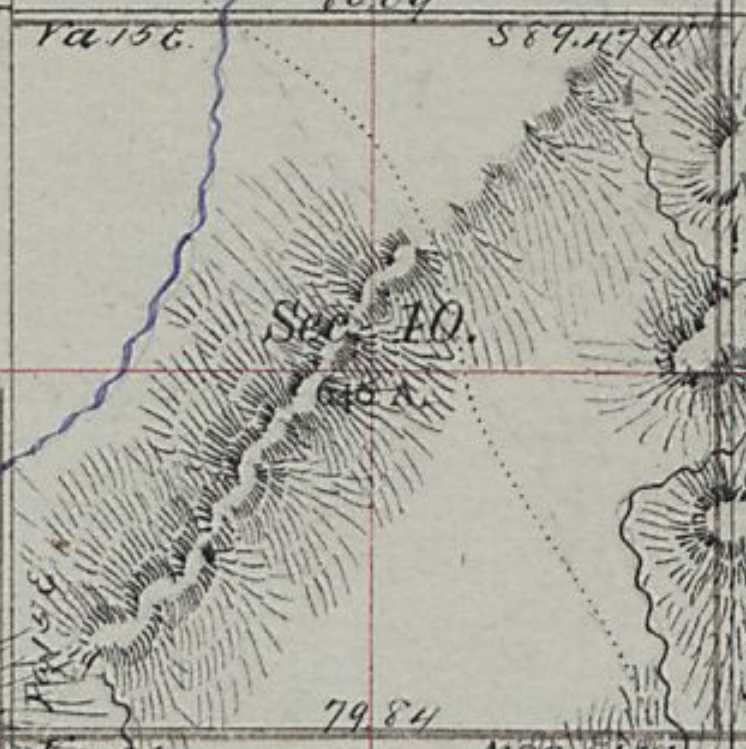

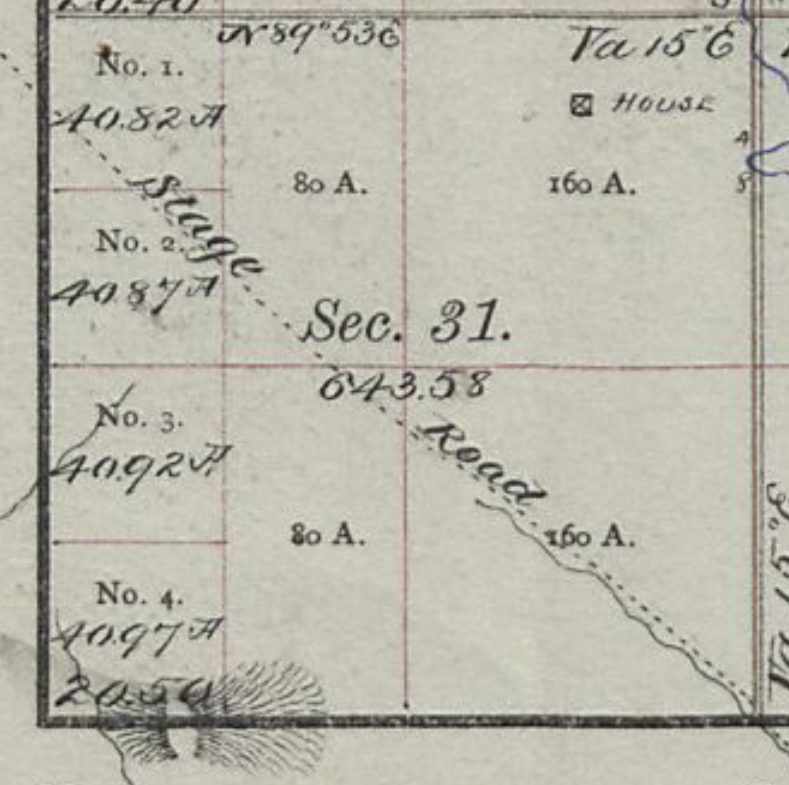

The location of Park Creek Station is not easily determined. Maps and descriptions are both similar and different. The landscape of today is vastly different than of the 1860s. Defining a location as “4 miles east of ..” does not work well; even worse when the “east of” location is itself not specific.

For no reason to think differently and speculating from information on the 1872 maps, I favor the first given location … but there is also evidence to suggest the second is a feasible location.

40.753636521313204, -105.12355365051921

9N69WS16NENW

or maybe

9N69WS09NWNE

40.76716165204707, -105.1280416218216

The Park Creek Station which replaced Bonner Springs was located on the “new” Overland Trail as established in 1862. This was located about four miles due east of the Bonner Springs Station and about four miles south of “The Amphitheater”. The Park Creek station was built on the banks of Park Creek. The first station was built of logs and was destroyed by Indians. It was rebuilt as a larger and more defensible station to accommodate overnight travelers although not considered a home station.

I’ve found no real information about this station and only vague information of its location. It appears nothing remains but it is claimed there is some evidence of a foundation with rubble. The area has been ranched and irrigated with modern roads and power lines passing through such that a specific location of the trail or station in this area is impossible to determine even with aerial maps. It’s likely the locals have better information – if they’re willing to disclose it.

It is also unclear as to whether a new route heading north from LaPorte was used or if the trail passed east through Owl Canyon. It’s likely both were used.

I tend to favor this location … somewhat south of Owl Canyon – but it’s roughly 4 miles east of Bonner Springs and 4 miles south of the amphitheater (a prominent geological structure). This would suggest a route directly north from LaPorte, not passing through Owl Canyon, although the old trail was probably kept in use and Owl Canyon is a convenient break to the other side of the dividing ridge.

directly under the number “16”

Weld County Rd 70 passes along upper edge (section boundary)

roads do not agree with 1877 map

While the crossing point of section line agrees with old map,

stage route would have angled to right of trees

There is a coarse map that suggests a location a bit north of this location. The map is grossly inadequate for determining a specific location.

Irrigation canal on right; station location between creek and ditch

too much activity in area to discern any trace of trail

Blacksmith Shop

10N70WS12SENE

40.84775662149922, -105.1726975972869

This was a note I made long ago … and now I can’t find the reference. Apparently, one version of the trail went past here – a trace is faintly visible to the left of the marker and this blacksmith shop was set along the trail just below a rough grade. The location is close to Park Creek and a road of sorts passes by.

The marker seems to be in the center of a diagonally placed rectangle which could be the outline of a foundation.

‘Twere it a different time in my life – and I didn’t now live so far away – I’d be tempted to check it out in person – if I could get to the location. Lots of fences and private land thereabouts..

just to the left of the marker

Maps of the area date well past the early days of the stage;

there are no indications the trail ran through here

The Amphitheater

About four miles up from the Park Creek Station is a large area in the shape of an amphitheater called “The Horseshoe” (even on some of today’s maps). Roughly one square mile in area and surrounded on three sides by high bluffs, it was a favored spot for stopping for the night.

In later days – after 1868 – the trail split here with one route headed to Cheyenne (which didn’t exist before the railroad that killed the Overland/Wells-Fargo stage); the other being the original route heading towards Virginia Dale.

There was a blacksmith shop near here doing business when wagons climbing the steep hills had broken down or whose teams needed re-shoeing.

(Gee, my radiator blew going up that hill and I have a flat tire)

After climbing up out of the Horseshoe, the route had to transverse “The Devil’s Washboard”. One of the most difficult sections of the trail heading in either direction.

These tracks line up quite well with the 1872 map

Artifact

10N69WS19SENW

40.81868017394476, -105.15999394395585

The area was in some ways less remote then than now. Various businesses were established along the route to provide services to travllers – not all of whom were stage riders. Blacksmith shops, saloons, other entities appeared her and there. All gone now, leaving little if anything in their wake.

Modern development – ranches and mines for the most part – have approached this region from the east, but the old stage road exists now only as faint tracks in the sands with nothing but debris and rotting foundations left of the business ventures of the past.

There is nothing definitive about the age of these remnants. A few words in diaries are basically all that tell of the locations of such endeavors – a specific site hard to pin down … and nothing to differentiate from the air a structure from “then” to something later.

40.819742229803886, -105.14976131362641

Signature Rock

Keeping on the route north to Virginia Dale, the trail goes down to Spring Gulch, passes many Indian Teepee Rings, and then on to Signature Rock, where it is claimed that names carved over 150 years ago can still be read in the sandstone. The location is a guarded secret and on private property. The region is full of sandstone bluffs …

Upon passing through Spring Gulch, the stages came upon one of the steepest sections of the Overland Trail. Named “Devil’s Washboard,” it is a steep, rocky incline–bad in both directions.

40.850816783386776, -105.21734129022987

6360 at top; 6130 at bottom 230 ft elevation in about 500 ft lateral

then back up to 6300 ft at a gentler grade to Cherokee Station

The welcome sight of a saloon for many drivers and passengers alike was at the bottom of Devil’s Washboard.

Possibly at 40°51’14.0″N 105°13’10.0″W ; the base of Devils Washboard

This is the historically rich area that has been the “Robert’s Ranch” for over 100 years. (Note: That portion of the trail from north of the Horseshoe, up past Spring Gulch and the teepee rings, to north of Signature Rock is where a mining company is proposing to strip mine. Please visit that page, read the information, and e-mail your opposition to the Larimer County officials named.)

A few traces of the trail are still visible from air; it may be harder to detect at ground level

This view represents the NW quadrant of the 1877 map to the left

Trail traces

It was imperative that the stage-coach axles be greased (or rather “doped,” as the boys used to call it) at every “home” station, and these were from twenty-five to fifty miles apart. This duty had time and again been impressed upon the drivers by the division agents, but occasionally one of them would forget the important work. As a natural consequence the result would be a “hot box.”

One afternoon early in the summer of 1863, while we were on the rolling prairies, one of the front wheels of the stage was suddenly clogged and would not turn. On examination, it was found to be sizzling hot. The stage had to stop and wait until the axle cooled off. As soon as practicable, the driver took off the wheel and made an inspection, the passengers and messenger holding up the axle. On further examination, it was found that the spindle had begun to “cut,” and there was no alternative but to “dope” it before we could go any farther. But we were stumped; there was no “dope” on the stage.

The driver, an old-timer at staging, suggested, since “necessity is the mother of invention,” that as a last resort he would bind a few blades of grass around the spindle, which he was certain would run us part way to the station, and we could stop and repeat the experiment. But one of the passengers chanced to have a piece of cheese in his grip sack, and a little of it was sliced off and applied ; and it worked admirably, and was sufficient to run the coach safely to the next station, where the difficulty was quickly remedied by application of the proper “dope.”

Cherokee Station

10N70WS05NWNE

40.861253143242386, -105.25797804712926 (cemetery per map)

Also known as Ten Mile Station, it was the last stop before Virginia Dale and was located just west of Steamboat Rock on Ten Mile Creek (Stonewall Creek on modern maps). It was said the Cherokee Station was burned out by Indians but a recent excavation found no evidence of charcoal, indicating that the station was probably not burned. Which does not mean the station was not attacked.

Just off the highway but on private property.

North of Cherokee, the Overland Route is essentially overlain with US287 although there are some variations. This segment of the old route is just south of the Virginia Dale church and on the west side of US287.

40.94360390207408, -105.34315301087189

Crossing of Deadmans Creek – coming into Virginia Dale

it appears US287 cuts directly through Morrison

40.87468183313786, -105.27203988587193 (center)

Heading about 10 miles north from Cherokee Station, the next station is Virginia Dale, perhaps the most famous of all Overland Trail stations. The station was named for Jack Slade’s wife while he was superintendent of the division. This is the last station in Colorado being less than two miles from the Wyoming border.

“The Indians were not the only source of annoyance in the early days. The Overland Stage Company’s employees were in many cases more carefully guarded against. They were a drunken, carousing set in the main, and absolutely careless of the rights or feelings of the settlers. The great desperado, Slade, who was for a time superintendent of this division, and was later hung in Montana by a vigilance committee on general principles, exhausted his ingenuity in devising new breadths and depths of deviltry. In his commonest transactions with others, Slade always kept his hand laid back in a light, easy fashion on the handle of his revolver. One of his most facetious tricks was to cock a revolver in a stranger’s face and walk him into the nearest saloon to set up the drinks to a crowd. He did not treat the passengers over the line any better.

Virginia Dale

12N71WS33NWNW

40.97346578856831, -105.36565494580627

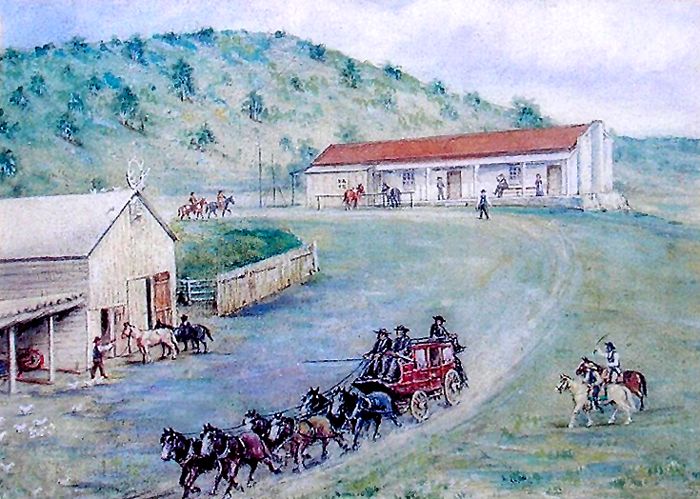

Virginia Dale was a “home station” on the Overland Trail, meaning that passengers could disembark, get a meal, and stay overnight in a hotel if the stage was delayed by weather or nightfall. Thirty to fifty horses were kept at the station which was located in a pleasant, grassy glade (or “dale”) along a clear bubbling stream, later named Dale Creek. Slade probably named the post after his wife Virginia, whose maiden name might have been “Dale”. Slade was an excellent stage manager as long as he stayed sober. Many stories credit him with outrageous actions from shooting up a saloon in LaPorte for serving his stage drivers whiskey, or for having “a fondness of shooting canned goods off grocery store shelves” [5] to robbing the stage of $60,000 in gold, which later disappeared. Slade was fired as stage manager in November, 1892 after a drunken shooting spree at nearby Fort Halleck and left with his wife for Virginia City, Montana where he was hanged in early 1894 by angry miners.

1865

“Virginia Dale deserves its pretty name. A pearly, lively-looking stream runs through a beautiful basin of perhaps one hundred acres, among the mountains – for we are within the entrances of one of the great hills-stretching away in smooth and rising pasture to nooks and crannies of the wooded range; fronted by rock embankment, and flanked by the snowy peaks themselves; warm with the June sun, and rare with an air into which no fetid breath has poured itself-it is difficult to imagine a loveable spot in Nature’s kingdom.“

At midnight we drew up at Virginia Dale Station … Nature, with her artistic pencil, has here been most extravagant with her linings. Even in the dim starlight, its beauties were most striking and apparent. The dark evergreen dotted the hillsides, and occasionally a giant pine towered upward far above its dwarfy companions, like a sentinel on the outpost of a sleeping encampment. – Edward Bliss, Overland Trail stagecoach passenger, 1862

“it was not uncommon to see 50 to 100 wagons with their loads of merchandise and freight encamped at the [Virginia Dale] station.”

Not far off to the east of US287, north of Fort Collins, Colorado, the Virginia Dale station is not accessible to the general public, but tours may be arranged. Jack Slade named the station for his wife, Virginia Dale Slade, and he was a successful manager for the stage line until his drunken tempers got out of hand. He was eventually fired from the Central Overland Stage Company. More on Jack Slade can be found here.

As division superintendent of the stage line, Slade worked from Julesburg in the east, along the South Platte to LaPorte, and up through Virginia Dale and along the southern route across Wyoming. He made his home base at Virginia Dale and managed stations spaced roughly 20 miles distant to Fort Bridger near the Utah line.

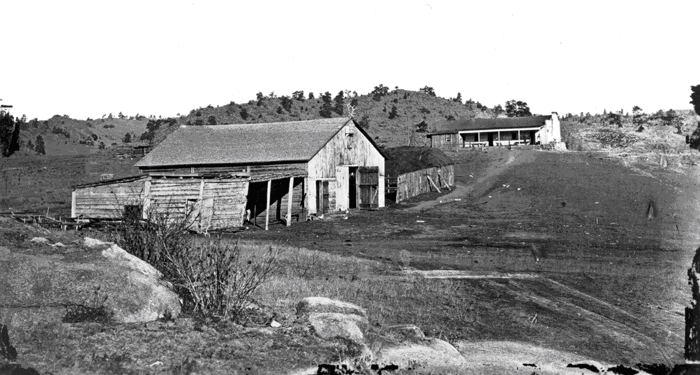

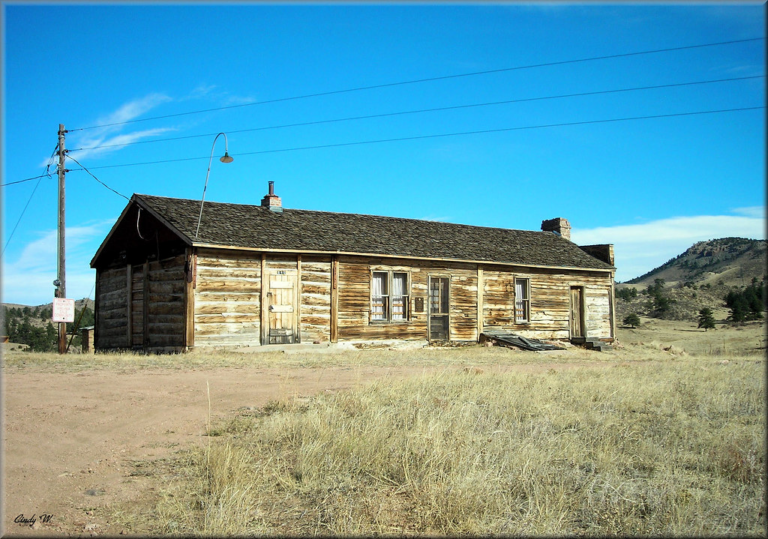

The Virginia Dale Station was built in 1862 and still exists as the only standing station on its original site. It sits on top of a knoll, north of the trail which is now a county road. The structure remains an intact hand-hewn log building and the location appears much as it did when the line was active.

Jack Slade not only managed the stage line, he oversaw the construction of the main building, the stables, and other out-buildings. A well was added a couple of years later. The station was of built of logs, but of a more uncommon mortise and tenon technique introduced by fur trappers who built cabins in the Rocky Mountains by this method.

station on knoll in background

The station consists of three parts with vertical posts separating each section and into which the end logs are mortised. The east and center unit have clapboard siding and were originally covered by an open shed-roofed porch. The building was used as a general store in the 1920s when the open porch was closed in. The porch was gone by the early 1940s. There was originally a shed on the west end section which extended to the edge of the porch.

The first shingles were brought in from St. Joseph, Missouri at the cost of $1.50 per pound. There were/are three doors on the front (south side); one for each section. There are two 1 x 1 windows in the center section and one 1 x 1 window in the east end. There are two pieces of log plate, joined over the center door. The back wall appears to be plain – no doors or windows.

Jack Slade is on the left, and his wife,

Virginia, for whom the station is named,

next to him.

An anomaly of the above picture: Note the position of the window and door as well as the length of the roof. If this is Virginia Dale Station, this must be one of the out-buildings – it does not appear to be of the main station building itself.

The east end has a parapet wall with chimney and 6 x 6 window. The corner posts have a continuous mortise which still shows the marks of the original auger. The wall extends above the slope of the roof which suggests that a second story addition to the east was planned – but there is no evidence such ever existed.

A large stone chimney is attached to the east wall with a six-over-six pane window to the side. Historic photos reveal that the stone rubble in evidence around the base of the chimney was present at the time of construction. By 1864 a hand dug well 65 feet deep and though solid granite was added.

In the early 1960s. tar paper siding was applied to the north wall to prevent snow from blowing in during winter. The chinking on the north wall has eroded leaving gaps between the logs. The window bays have been sealed but there presence is obvious from the inside.

The interior is one open room with log walls. Remnants of white wash is visible. The caretakers have placed a woodstove in the center of the room, using on the brick chimneys. The ceiling has been lowered from the original and the brick fireplace has been rebuilt.

There is a cellar under part of the station with access through a doorway at the front. The cellar stairs and walls are built with stone. The floor joists were cut at a reciprocating sawmill.

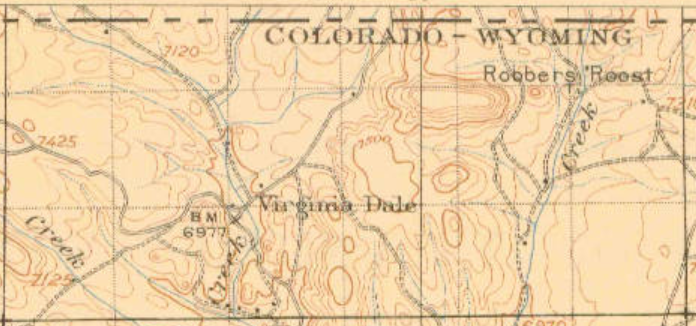

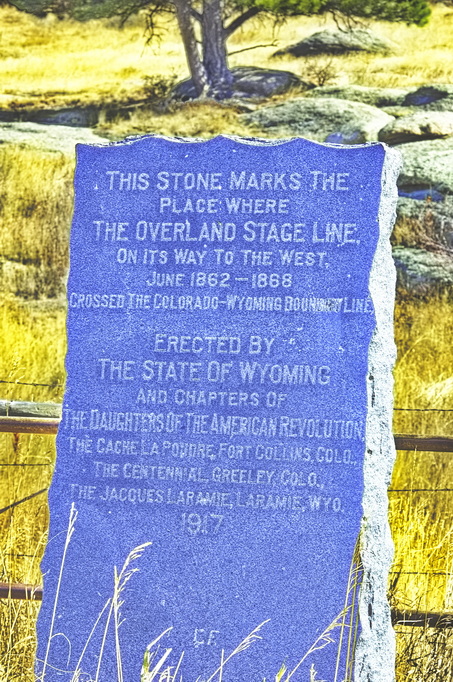

A little less than two miles north of Virginia Dale is the Wyoming border – then, Dakota Territory. Right on the Wyoming/Colorado border – which happens to be the peak of a hill – along Highway 287 is a granite marker placed by the DAR on July 4, 1917. The original crossing was actually about 1 mile east of this point.

but then, US287 is accessible and the actual crossing place is not

Contrary to the monument on the border at US287, the Overland Route

crossed into Wyoming a mile or so east of the highway.

What is labeled Mud Creek here is labeled Slade Creek on the older maps.

A stage carrying an army payroll of $60,000 in 10 and 20 dollar gold coins was headed for Fort Sanders [Laramie] in Wyoming. About a mile from Virginia Dale, the stage was robbed by six masked outlaws at Long View Hill. The gang took the strongbox from the stage and headed west towards the wooded foothills, where they blew the lock off the box, removed the gold coins, and buried them. The robbers were pursued and killed by the U.S. Cavalry (“Steal our pay, will you?“). The strong box was later found in a nearby creek, the sides and bottom gone, riddled with bullet holes – and empty. The money was never found.

Next: Across the Laramie Plains