Detailed Map: Duck Lake to LaClede

Large file; high resolution – will load in separate window

ORG dots are traces from 1870s surveys; PUR dots are traces from 1970s maps

PUR dots overlay ORG dots where trails coincide

Travellers entered the heart of the Bitter Creek country after leaving Duck Lake Station.

“Bitter Creek, which drains the country, is so impregnated with alkali that neither man nor beast can drink it without injury; and the wells at the stations are almost equally bad. The water if drunk in the usual quantities, produced violent nausea, and does not satisfy thirst. Even in coffee and tea, it is tasted, and the ‘square meals’ seem throughout as if alkali had been spilled profusely on everything”.

“Bitter Creek is too miserable a stream to have a name. Tho’ I don’t know [how] Emigrants would get across this desert country without it.”

About 4 miles west of Duck Lake is a prominent red rock at the entrance to Barrel Springs Draw. Travellers sometimes stopped here and carved their names into the rock.

Red Rock

17N94WS21SENW

41.43289815903132, -107.99354783765516

Unfortunately, photos didn’t turn out

“For sixty miles on Bitter Creek, Wyoming, the soil is a mass of clay or sand and alkali–a horrible and irreclaimable desert, which has made the place a byword. For a few days our average elevation was 7000 feet above sea-level and the nights were extremely cold. On the 22d we reached Bridger’s Pass, and next day entered on the Bitter Creek region–horror of overland teamsters–where all possible ills of western travel are united. At daybreak we rose, stiff with cold, to catch the only temperate hour there was for driving; but by nine A.M. the heat was most exhausting. The road was worked up into a bed of blinding white dust by the laborers on the railroad grade, and a gray mist of ash and earthy powder hung over the valley, which obscured the sun but did not lessen its heat. At intervals the ‘Twenty-mile Desert,’ the ‘Red-sand Desert’ and the ‘White Desert’ crossed our way, presenting beds of sand and soda, through which the half-choked men and animals toiled and struggled, in a dry air and under a scorching sun.“

Passing through Barrel Draw, the road passed by Barrel Springs – a source of better water than Bitter Creek provided.

Barrel Springs

17N95WS24SWSE

41.42940015349809, -108.05580424074775

I did not stop at this location; passed by about ½ mi south.

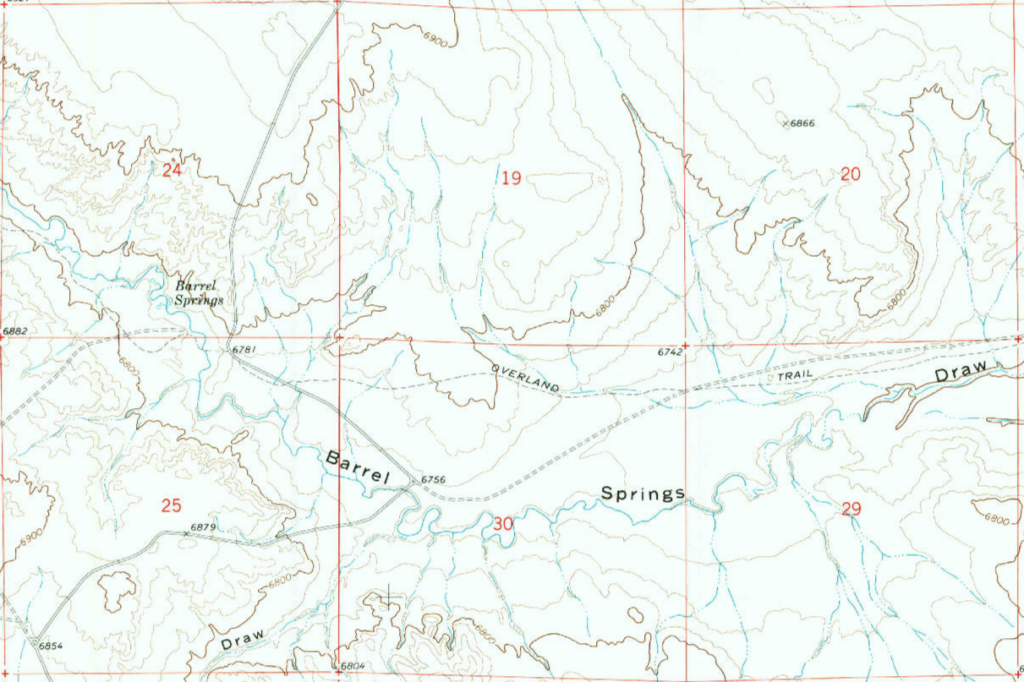

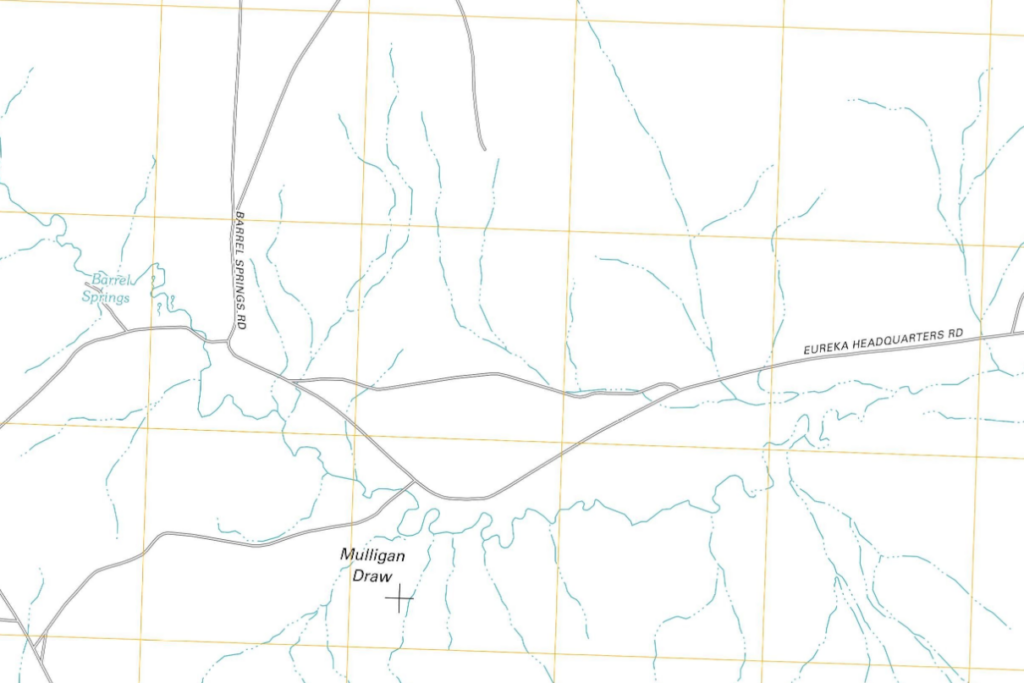

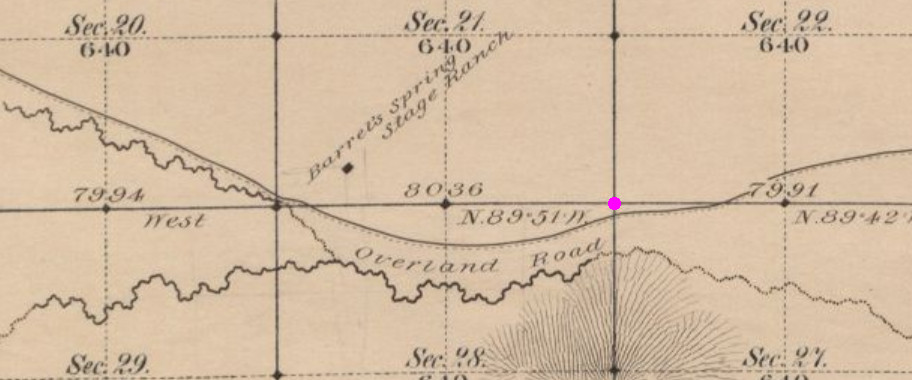

An example in mapping differences. The one on the left is a 1970 USGS map, updated in 1985. The map on the right is the same USGS, issued in 2012. I’ve found the USGS maps issued in the late 60s to early 80s have the most complete information … but I have greater faith in roads plotted on the 1870s survey maps being the Overland Road – the actual road would have still existed and was probably still in use.

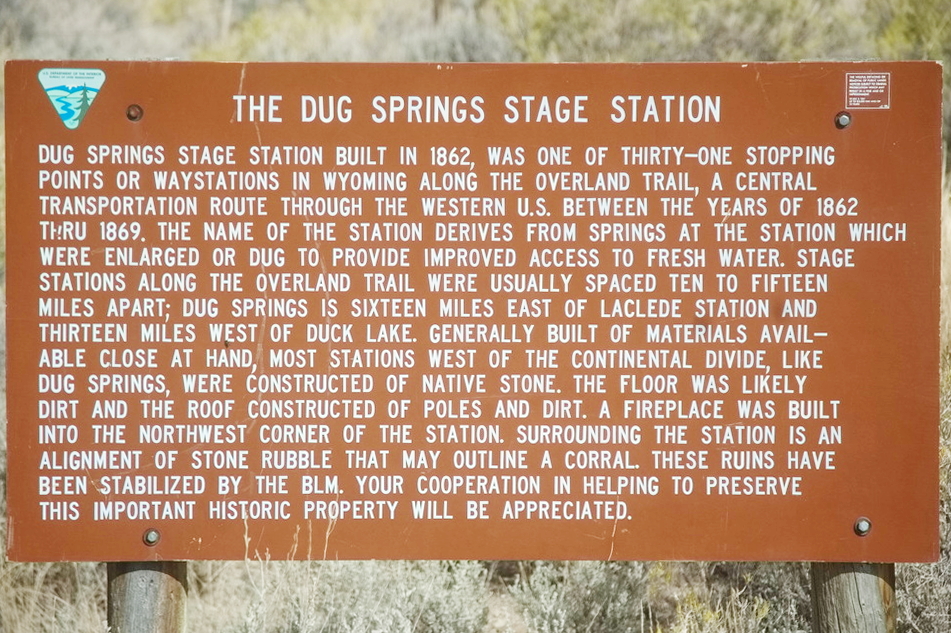

Dug Springs Station

17N95WS20SESE

41.42926883265362, -108.12588764811912

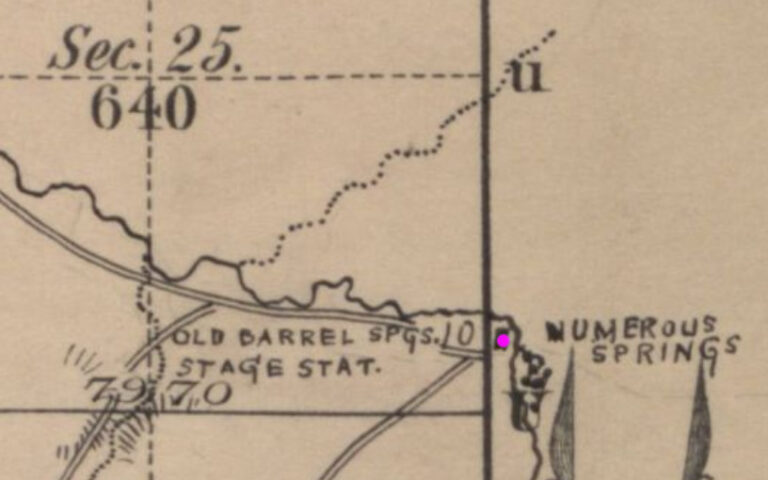

The Dug Springs swing station is located along a small dry wash. The buildings were built of flat slabs of local stone. As was typical of the swing stations, the floor was dirt and the roof of dirt-covered poles. The foundation and lower walls of one building are located within a fenced enclosure, which also contains a BLM interpretive sign. Civilization even in the boonies. The springs are visible along the east side of the station as two circular areas of wet earth. Several miles of intact Overland Trail ruts run through the site. The 1870s map refers to this as “Barrel Springs Stage Station”, likely as the hand-dug wells probably used barrels as lining.

The two locations are roughly ½ mile apart

Note from above, the “Barrel Springs” is in Section 21

Benchmark below location in MAG

The right place

Section 20 closeup

old map station location

After examining the old survey maps over the entire distance, I’ve rarely found them to be of this magnitude disagreement with modern satellite imagery.

On the other hand, could I convince myself that “something” exists within the marked rectangle that seems to be in the location indicated on the old map? Possibly a “rebuild”? Such straight lines don’t commonly exist in nature. It would take a visit on the ground to determine such.

Possible artifact in near agreement with 1870s map

I didn’t know of this discrepancy when I was on-site

Evidence on the ground suggests the old map is wrong …

The trail along here is now known as “Eureka Headquarters Road”

The Dug Springs Stations was considered by some to be the most impressive of all the Bitter Creek stations. A pit was dug below the spring and a barrel was sunk into the ground to catch the water. The ruins are near Middle Barrel Springs Canyon.

Dug Springs to LaClede

The recent tire tracks are mine

In places, the road is maintained for mining efforts.

In some places – Duck Lake the most notable – this “improvement” has destroyed traces of the Overland Road and stations.

Sometimes the old trail is impassable due to nature, not man

Standing on the trail at the edge; the trail goes/went straight ahead

LaClede Station/Fort LaClede

17N98WS26NESW “station”

41.42279483703006, -108.41397836476818

17N98WS25SESE “fort”

41.41473123597759, -108.3899121823751

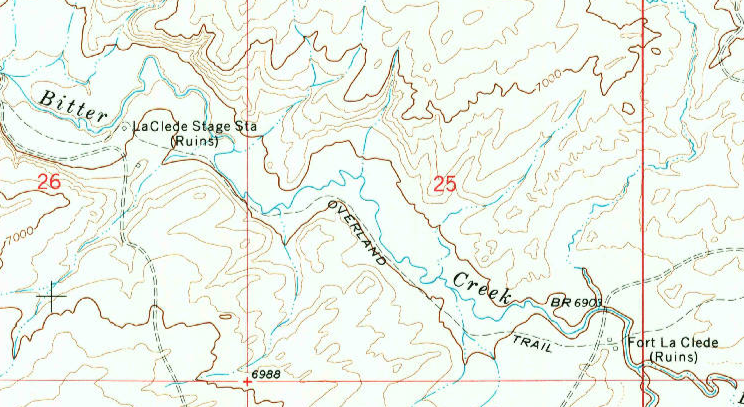

The LaClede home station is located near the head of Bitter Creek. The remains of two large buildings are present within a fenced enclosure. For many years in the twentieth century, the LaClede home station was known as Fort LaClede, but this is incorrect. No known nineteenth century document describes LaClede as anything but a stage station and no known nineteenth century document refers to any site as Fort LaClede—as they do for Fort Bridger or Fort Halleck. Also, there are no known U.S. Army records for a military post on the Overland Trail between Fort Bridger and Fort Halleck. Soldiers were deployed intermittently at LaClede and many other stage stations during the 1860s, but this does not make these stations formal military outposts. “Fort LaClede” is now considered to be a twentieth century invention.

In spite of the above statement, the 1870s map puts the station at what is now labelled as Fort LaClede. There is no marking on the old map at what today is labelled “LaClede Stage Station”. The 1870s map also refers to the Fort LaClede location as “Barrel Springs Station”. This location matches that of Fort LaClede on modern maps.

Regardless of nomenclature, there are two sets of ruins remaining along Bitter Creek at the locations indicated on the modern map below.

There has been a bit of question regarding two sites with a bit less than 1.5 mi between them. Both – in different places – have been noted as the station site, however, the site northwest of Fort LaClede has been identified as the LaClede stage station. That site is now identified as the early twentieth century Boyer sheep ranch – and it doesn’t appear as the stage station on the 1880s map.

The LaClede Stage Station was originally built as a home station. Like the other stations, it was subject to Indian raids and highwaymen. On August 25, 1869 four men and a boy, all masked, stopped the stage just west of the LaClede Station and took $42,000 in gold bars and greenbacks. During the confusion of the holdup and getaway, the boy found himself lost. He eventually wandered into a near-by Union Pacific work camp where he confessed. Soon thereafter he joined the lawmen looking for the bandits, and the stolen gold. They lost the trail in lava rock, the money wasn’t recovered.

Although it was never officially a “fort” in military parlance, soldiers from the 11th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry were posted here. In June 1865, several soldiers skirmished with Indians a few miles east of the station. The soldiers were drawn into an ambush and were rescued by other soldiers, assisted by employees of the stage station. The designation of “Fort” was probably just a nickname.

The ruins of the Fort LaClede station are the most impressive along the Bitter Creek section. The station was one of the most defensible; it included barracks, a corral, gun tower, and telegraph office. Gun pits were built on surrounding hills. The corrals were large enough to hold a large number of horses. The telegraph line provided the only link – other than traffic – to the other isolated stage stations and forts.

The two buildings of the station were several feet apart, each constructed of a local sandstone formed from the mud of an ancient lake bed which long ago once covered this area. The walls of the station consist of a double row of rock. Like most defensible positions, this site has a good view of the surrounding country from all sides. The smaller of the two buildings appears to have been about ¼ the size of the larger building. Evidence suggest the Overland Road passed between the two buildings.

What are likely gunports are present in the remaining walls of the buildings. The openings are small and do not appear suitable for any type of windows. During winter weather, the openings were probably covered with whatever was handy to keep out the cold and wind.

A telegrapher stationed at the LaClede Station only known by initials H.E.R. reported an attack on the station. Summarizing from a letter to the April 25, 1868 copy of “The Telegrapher” (an image of the original letter here):

About 3PM in June 1867, “the Indians commenced “raiding” on the line of the Stage road“. At the time, only five men and two women were present – including the telegrapher HER. Making preparations to defend themselves, they moved into the more substantial building.

“The first intimation we at the head of the Creek had of them was finding our “ranche” surrounded by about two hundred Sioux.”

The occupants were under-armed, having only three muzzle-loading muskets – two of which were broken, the third having no ammunition. The only available weapon was HER’s Derringer with a good supply of ammunition. A Derringer is a small, short-range .41 caliber pistol.

The Sioux did not know this.

HER: “I sat at my instrument, reporting the movements of the enemy to Salt Lake ‘C’ office. The Indians did not attack us that P.M., but amused themselves burning poles; and my principal and oft-repeated report to ‘C’ was, ‘There goes another pole.’ The line finally opened, and that stopped any report West. I worked East for half an hour longer, when that circuit also opened.”

“As ‘Injuns’ were too thick for me just then, I did not go out on the line until after dark. Starting just after dark, I rode immediately under the line for about nine miles, when I found the break. They had cut down four poles, and carried off about one mile of wire. It took me two days to get that break fixed up, as I was without assistance.”

HER does not mention what happened to the horses nor whether any shots fired. The published account is simply a quick note which does not go into detail about why the war party didn’t attack the station and was satisfied with only burning telegraph poles, cutting the lines, and taking off with a length of the “talking wire.”

“This is only a specimen of our experience all summer … It is a very exciting experience, and can not be compared with life in the East…“

Stagecoaches ran year-round. A February (3?) 1867 New York Times article [behind paywall] described a stagecoach traveling blind through a blizzard. Without knowing it, the stage driver drove up onto the roof of the LaClede Station barn.

A description was written on July 28, 1865: “we crossed Bitter Creek, a nasty looking stream. The water looks green and is poison…. There is a stone house just this side with three rooms and a porch and a stone wall around the lot I saw one very nice looking lady here”.

Although the stage stations were built and maintained specifically for the benefit of the Overland Stage and Mail, emigrants could make use of these services.

Drove until one o-clock through an awful dust waste and came to the headwaters of the long sought but unknown stream to travelers, known as Bitter creek where we drove our stock four miles to grass and water, whilst McMahan, Doc Bernard and myself went to the ranch [Laclede station] nearby, sought and obtained a warm breakfast. The lady gave us cream in our coffee, butter and cornbread, pies and molasses three times passing bacon and last but not least, bountiful supply of Black-tail Deer steak, which was most excellent indeed. This however came very near being the cause of our excommunication from our regular mess at camp as our most worthy and accommodating cooks John Vaughne and Jerry Lewis gave us most emphatically to understand they would not by any means permit a repetition of the like again.

Station keepers were not always as generous to travellers as the woman at LaClede. An incident in 1866 had the Duck Lake station men trying to force a traveller to buy water from their well by hiding the bucket. In 1863, those at the Salt Wells station also tried to sell well water to travellers.