Detailed map: Rock Springs to Lone Tree

Detailed map: Lone Tree to Church Butte

Detailed map: Church Butte to Fort Bridger

Leaving Rock Springs, the routes presented in the 1880s and 1980s maps diverge again. The older map shows the route heading west then veering a bit south to follow the base of bluffs west of what is now town (Rock Springs did not exist until the railroad arrived) while the 1980s map shows the route looping to the south immediately after leaving the station and following not too far from the path of I-80 along what is now Sweetwater Dr.

Northwest of the town itself, in the newer developments, is Stagecoach Elementary School which has preserved sections of the old trail. There has been sufficient development and trail riders that the actual route is now indiscernible from the multitude of other trails in the area.

The two mapped trails converged near what is now Exit 101 on I-80. In general though, the old maps indicate the trail more closely follows the path now taken by I-80 while the newer maps indicate a trail more closely following Bitter Creek.

The “Old Lincoln Highway” was built on the Overland Road

Section of Lincoln Highway/Overland Road from I-80

Both mapped trails converge at the eastern side of the (now) town of Green River, crossing the Green River itself at the same location.

Green River

18N107WS27NENE

41.51624569854642, -109.46394306617003

The Overland Road left the modern I-80 corridor at Green River.

If both the old and new maps are to be believed, the Green River home station was located on a site now occupied by a storage facility next to the Wyoming Game & Fish Regional Office on the south bank of the Green River … as usual, recall there was no town of Green River or railroad at the time.

This station was headquarters for the Green River Division. There was no bridge over the river; stagecoaches had to ford the river or use the ferry. When the water was low, it was an easy crossing over a gravel river bed but during spring run-off when water was high, it cost $20.00 to use the ferry. There are no remnants or even signs the station existed at this site.

The Overland Road was heavily traveled at this point – aside from the Overland stage, travel back and forth from Utah and California along with traffic to the gold fields of South Pass passed through this location. The Oregon Trail also crossed the Green River here, heading off to the northwest. The town was laid out in 1867 – after Wells-Fargo took over the stage line – and by the time the railroad came through in 1868, the town of Green River held about 2000 people.

John Wesley Powell started his famous 1869 trip down the Green and Colorado Rivers from this point.

Leaving the station heading west, the trail roughly followed today’s Riverview Dr to the entrance of what is now Telephone Canyon. The trail once again leaves the I-80 corridor, avoiding the rough country along the Green River.

Faint traces of the Overland Road are still visible in the deserts W of Green River between the Green River and Black’s Fork.

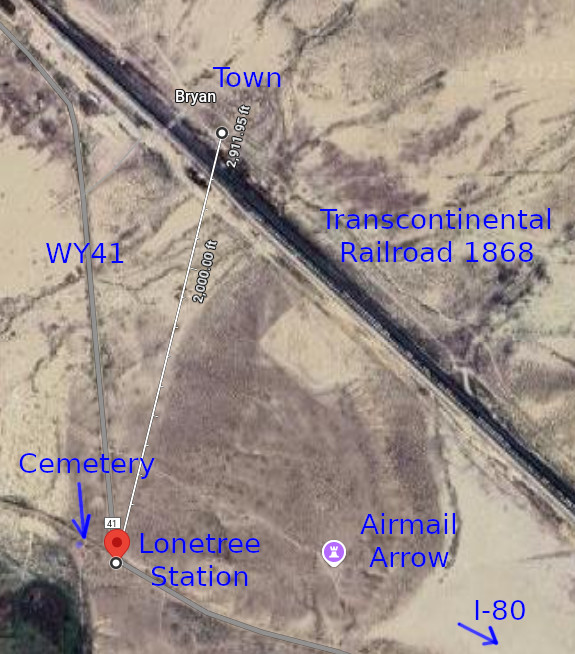

Lone Tree Station

18N109WS11NWNE

41.56213337975896, -109.68330492130016 station

41.56232293659932, -109.68410429017317 cemetery

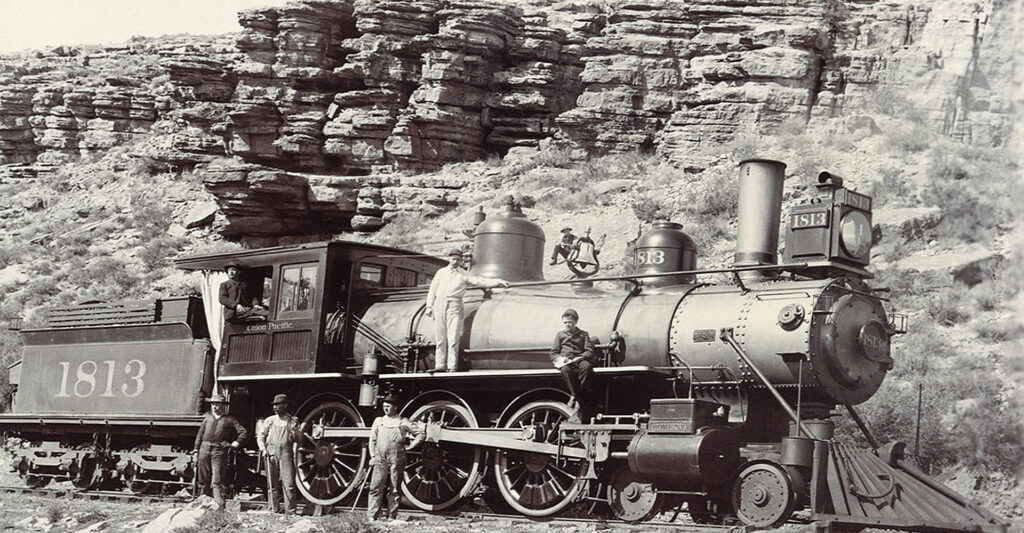

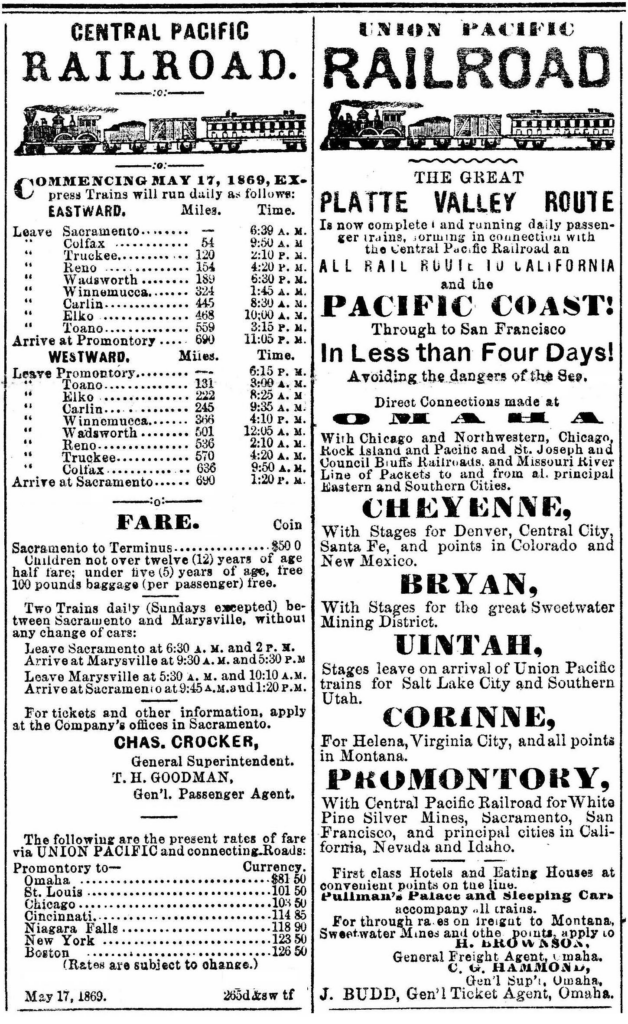

The Lone Tree swing station was named for a nearby large and solo pine tree. There was considerable railroad activity after the Overland/Wells-Fargo companies gave up operations in the area as the town of Bryan – less than 1 mile from the original stage station – was established in 1868 as a division point for the Union Pacific Railroad for a short time. By December 1868, the population of Bryan had increased to 5,000. It’s not surprising remains of the stage station have disappeared.

Bryan, WY

41.570209369929955, -109.68175282298166

The Winter Town, UPRR (1867)

Bryan is located on Black’s Fork on the line of the UPRR and will be the terminus of the Railroad for freight and passengers during the coming winter, and probably until the connection is made between the UPRR and the Central PRR. Bryan is the most accessible point to the Sweetwater mines, and will unquestionably be The Best Town for trade between Omaha and Salt Lake City. Large machine shops and a Round house will be built there immediately. Now is the time to purchase lots at the low valuation placed on them by the Railroad company.

Bryan contained a twelve-stall roundhouse, warehouses, and machine shops as well as restaurants, a boot maker, gunsmith, bank, and concert hall. As an “end of the tracks” town, Bryan thrived—a wild “hell-on-wheels” frontier community. Bryan also served as the major jumping off point for travel north to the Sweetwater Mining District and the gold mines around South Pass City eighty miles to the northeast. Within a few months, Bryan had a population of 5000 but Blacks Fork dried up to the point where there was insufficient water to fuel the engines so the UP shifted operations to the town of Green River and the population moved with it. By 1872, Bryan was a ghost town. There are few remains of Bryan left – and none of the original Overland station. There is a cemetery near the station site.

About ¼ mile due east of the station site is an airmail navigation beacon arrow from the 1920s

41.562083547773554, -109.67807590330872

From Lone Tree, the trail followed along Blacks Fork – the same path the Transcontinental Railroad selected, looping to the north along the river before turning back southward. Along this stretch, the Overland Central Stage Route could be said to end as it re-joined the original line – the California Trail – about 5 miles east of Hams Fork Station. One of the take-off points for the Oregon Trail for those skipping a stop at Fort Bridger is located here.

Hams Fork (South Bend/Granger)

19N111WS32NENW

41.59055113214179, -109.96987990416216

This station still exists – mostly. It is located along what was once US30. Now, no highway passes through, one has to turn off the main road to even get to town.

The area had been known for some time; it was the site of one of the “Mountain Man” rendezvous in 1834 which was recorded as being at the confluence of Hams Creek and Blacks Fork. The population has never been large though – once supported by stage operations, now supported by railroad operations.

While the trail normally crossed near the junction of Hams Creek and Blacks Fork, 18 miles beyond Lone Tree. The actual site crossed Ham’s Fork at various locations depending on current conditions. Usually, it was an easy crossing, described in 1847’s “The Latter-Day Saints’ Emigrants’ Guide” as:

“Ham’s Fork, 3 rods wide, 2 feet deep. Rapid current, cold water, plenty of bunch grass and willows, and is a good campground.”

The condition of the river depended a great deal of when it was to be crossed. Several parties came to the crossing in 1849; some arrived early in the season when the river ran swift and high.

In early June 1849:

“[T]raveled fourteen miles to Blacks Fork, followed up another four to Hams Fork where we ferried our things in a skiff of rough architecture two dollars per load. Had to swim our horses, river forty yards wide. Ferry kept by half-breed Indians and French. Traveled three miles and camped on Blacks Fork.”

Later in June 1849:

“By measurement we ascertained that to ford it without damaging our goods in our wagon, it was necessary to elevate their beds a few inches; and further to aid in crossing we were obliged to use ropes, these being fastened to the forward axles, and carried to the opposite shore; while with others tied to the mules in the lead they were kept from being borne down stream by the rapid current. In all this we succeeded admirably, although at the outset we feared that we should be necessitated to ferry across as at Green River.”

By mid-July 1849:

“[A]bout nine o’clock struck Ham’s Fork, a tributary of Black’s Fork, a beautiful little mountain brook, clear as crystal, rattling over a pebbly bed. Its banks were clothed with rich grasses and fringed with alder and willow.”

A ferry was established as an on-again, off-again operation. In 1850, the ferry owner was back and ran the ferry for about a month when water was high.

In early June 1850:

“Thence to Hams Fork, a small stream sixty feet wide, very swift current. Too high to ford. We ferried our things in a wagon box and swum our horses and wagon. Here we came very, very near having one of our horses drowned by getting his feet entangled in the reins of his bridle. F swam in after him and came very near drowning himself.”

Yet later that month, a man named Silas Newcomb wrote:

“… the water was deeper and the grass had been “eaten down and passed on. . . . the water wet our wagon boxes, though not to injure anything in the wagons. … Here also was the lodge of the now idle ferryman who had a squaw and several half breeds around–he had a large number of horses and oxen, cows & calves. Soon after leaving Ham’s fork we rose a small hill, and found on the left of the road a grave ‘N. Tharp, died Aug. 6th, 1849.’”

During the Mormon War of 1857, the army established a post here and built a bridge at the crossing. It was short-lived and seldom used … and no explanation as to where and why.

Richard Burton was a famous English world explorer of the day. In 1860, he travelled to California by the Overland Stage and wrote of Hams crossing:

The mail station and future Pony Express and telegraph station was in a small cove on the north side of the stream and was described well by British travel writer Richard Burton, who arrived there on Aug. 22, 1860. Like Greeley, Burton was traveling in a stagecoach.

“At mid-day we reached Hams Fork, the north-western influent of Green River, and there we found a station. There pleasant little stream is called by the Indians Turugempa, the “Blackfoot Water.” The station is kept by an Irishman and Scotchman—“Dawvid Lewis:’ it was a disgrace; the squalor and filth were worse almost than the two–Cold Springs and Rock Creek–which we called our horrors, and which had always seemed to be the ne plus ultra of western discomfort. The shanty was made of dry-stone piled up against a dwarf cliff to save back-wall, and ignored doors and windows. The flies–unequivocal sign of unclean living!–darkened the table and covered everything put upon it.”

David Lewis, a Scottish Mormon, managed station operations with his two wives and large family. He was actually a native of New York, but his two wives, sisters, were from Scotland.

In 1864, Horace Greeley (“Go west, young man“) wrote:

“Eighteen miles [from the Green River] more of perfect desolation brought us to the next mail company’s station on Black’s Fork, at the junction of Ham’s Fork, two-large mill streams that rise in the mountains south and west of this point, and run together into Green River. They have scarcely any timber on their banks, but a sufficiency of bushes—bitter cottonwood, willow, choke-cherry, and some others new to me—with more grass than I have found this side of South Pass. On these streams live several old mountaineers, who have large herds of cattle which they are rapidly increasing by lucrative traffic with the emigrants, who are compelled to exchange their tired, gaunt oxen and steers for fresh ones on almost any terms”

Perhaps not …

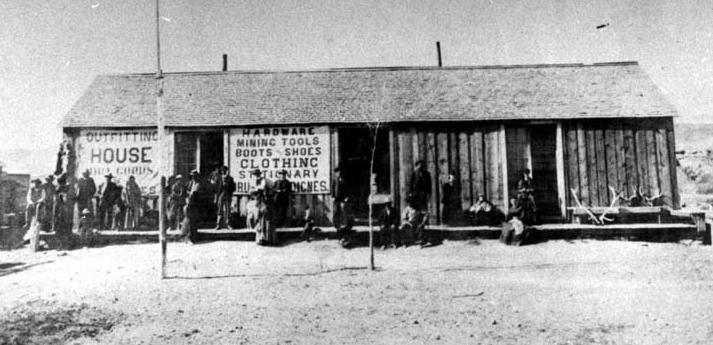

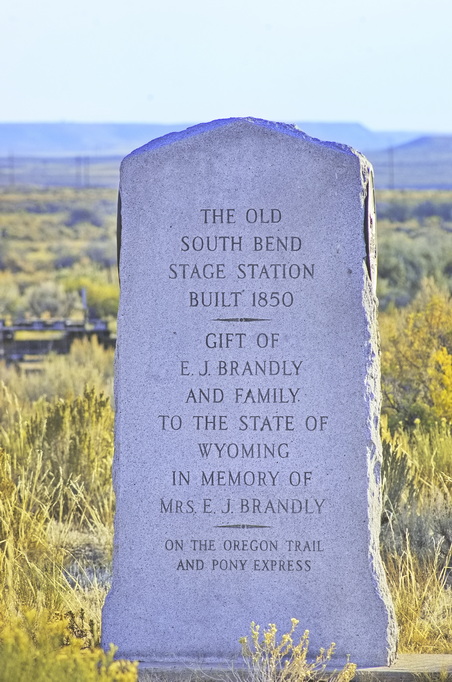

The Hams Fork crossing was also named South Bend after the station was established in 1850 for use by mail contractors going to Utah. It became a Pony Express Station in 1860, then later an Overland Stage home station. The site was renamed Granger after the first postmaster when the railroad came through in 1868.

Possibly a William Henry Jackson photo of 1866

There is some evidence the original station was the crumbling section to the left

US30 passes by in front

The station exists but has been restored by the National Park Service. There is some thought that the restoration was actually a replacement of the earlier building established by Ben Holladay in 1862. The noted western photographer William Henry Jackson worked for a few months as a teamster for Holladay and spent three weeks at the station in 1866.

Richard Burton again, from his journal:

August 22, 1860 – 2:00 pm to 5:15 pm: 20 miles: Ford Ham ‘s Fork . After 12 miles the road forks at the 2d striking of Ham ‘s Fork , both branches leading to Fort Bridger. Mail takes the left hand path. Then Black ‘s Fork, 20 x 2 , clear and pretty valley, with grass and fuel, cotton-wood and yellow currants. Cross the stream 3 times. After 12 miles, “ Church Butte.” Ford Smith ‘s Fork, 30 feet wide and shallow , a tributary of Black ‘s Fork. Station at Millersville on Smith ‘s Fork ; large store and good accommodation.

Church Butte

18N113WS32NENE

41.504198307448924, -110.13809229297743

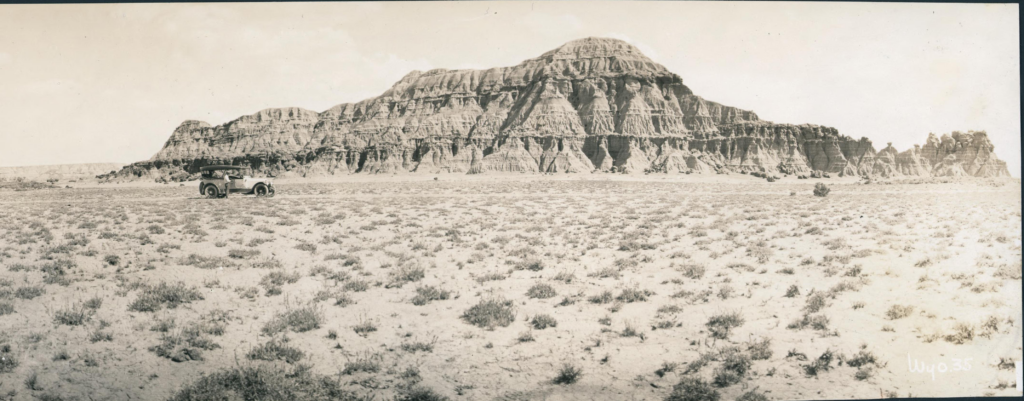

Church Butte is a soft sandstone and clay hillock standing alone to the south of the Oregon-California Trail as it heads southwest toward Fort Bridger. The 100ft tall butte was an important landmark on the route between Green River and Fort Bridger and is located about 10 ten miles southwest of Granger alongside a road that was once US30. A gas station once stood just across the road but the area is now deserted and just as desolate as it was in trail days, though at one time …

The name Church Butte did not come into general use until the 1850s. Before that, emigrants (mostly Mormon at that time) made up their own names – if they even bothered – often comparing its knobs and eroded towers to imaginary castles and pyramids.

An 1853 description:

“Just before arriving at Black’s Fork, [ford] No. 3, where we camped, we passed as splendid range of clay bluffs which, as we passed them, seemed covered with figures in almost all attitudes—nuns confessing to priests, and warriors fighting, and transforming and varying themselves as we changed our position.”

Richard Burton, 1860:

“After twelve miles we passed Church Butte, one of many curious formations lying to the left or south of the road. This isolated mass of stiff clay has been cut and ground by wind and water into folds and hollow channels which from a distance perfectly simulate the pillars, groins, and massive buttresses of a ruinous Gothic cathedral. The foundation is level, except where masses have been swept down by the rain, and not a blade of grass grows upon any part. An architect of genius might profitably study this work of nature: upon that subject, however, I shall presently have more to say. The Butte is highly interesting in a geological point of view; it shows the elevation of the adjoining plains in past ages, before partial deluges and the rains of centuries had effected the great work of degradation.“

One source suggests Church Buttes was a Pony Express relay station; another mentions Church Butte as a stage station without mentioning the Pony Express. It has been noted that the 1861 U. S. mail contract does not mention Church Butte as a station.

The road now passing by is at best a tertiary route, remote with little traffic, although once part of the only cross-country highway and later US30.

Church Butte to right

More or less the Overland Road

Name Rock

17N113WS33NESW

41.413450933340464, -110.17941950478492

Along about 7 miles west of Church Butte was what is known as Name Rock. Not so much for the stage passengers but this section of the Overland Road was a major highway in its day, all roads heading for Fort Bridger, the nearest supply/repair station. Travellers stopped by this rock formation and carved their names.

I did not stop to examine the area.

The modern road follows the north bank of Blacks Fork, albeit without the curves of the river – while the Overland Road stayed along the south bank until the crossing at Millersville.

Millersville

16N114WS01SESE

41.390406276237435, -110.20524268137544

The 1861 mail contract names Millersville as a station named for A. B. Miller, one of the partners of the Russell & Waddell freight line and popular stage driver. The station was built where the old emigrant trails crossed Smiths Fork, near its confluence with Blacks Fork. The location was originally settled in 1834 when “Uncle Jack” Robinson, a friend of Jim Bridger’s, built his home there. Uncle Jack later established a trading post at the site. Later, a Mormon named Holmes ran the trading post and managed station operations. The Millersville Stage Station was also a Pony Express relay station.

The site is private property

About 2 miles shy of Fort Bridger, the Oregon Trail cut off NW to Fort Hall. One would believe travellers on this route pulled into Fort Bridger for rest and supplies before taking off to the north but that would probably add a day or two to travel time.

At Millersville, the trail re-enters the I-80 corridor. The Overland trail followed closely to the southern bank of Blacks Fork; I-80 runs a bit north of the creek.

From Fort Bridger, the Overland Road went west then looped south away from the I-80 corridor heading for Salt Lake City. The Fort Bridger museum is about 2½ miles from I-80, Exit 34.

Fort Bridger

16N115WS33SWSW

41.317966546162125, -110.38910989192065

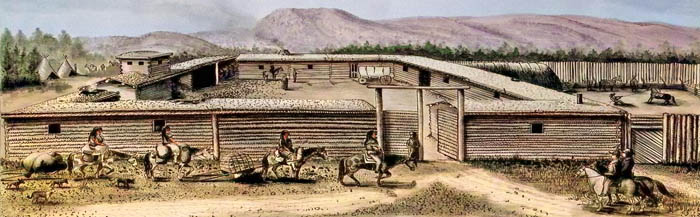

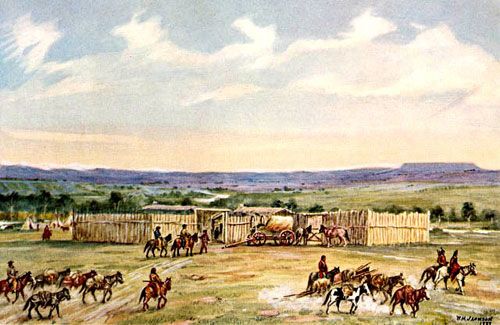

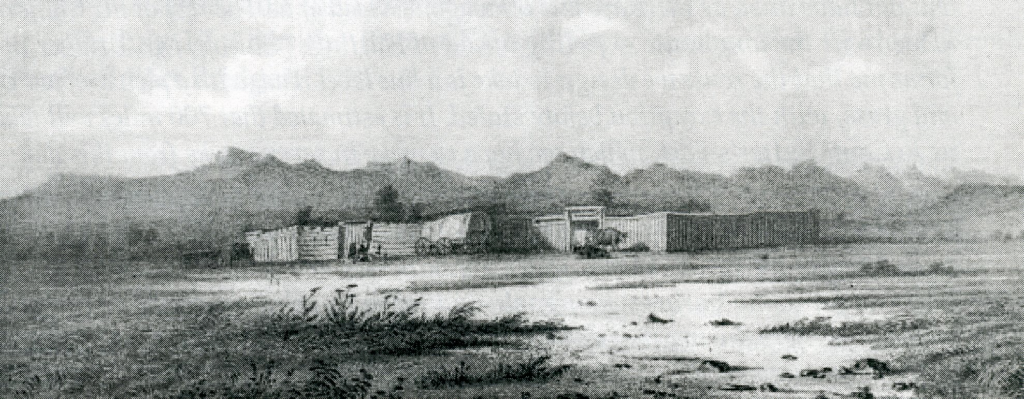

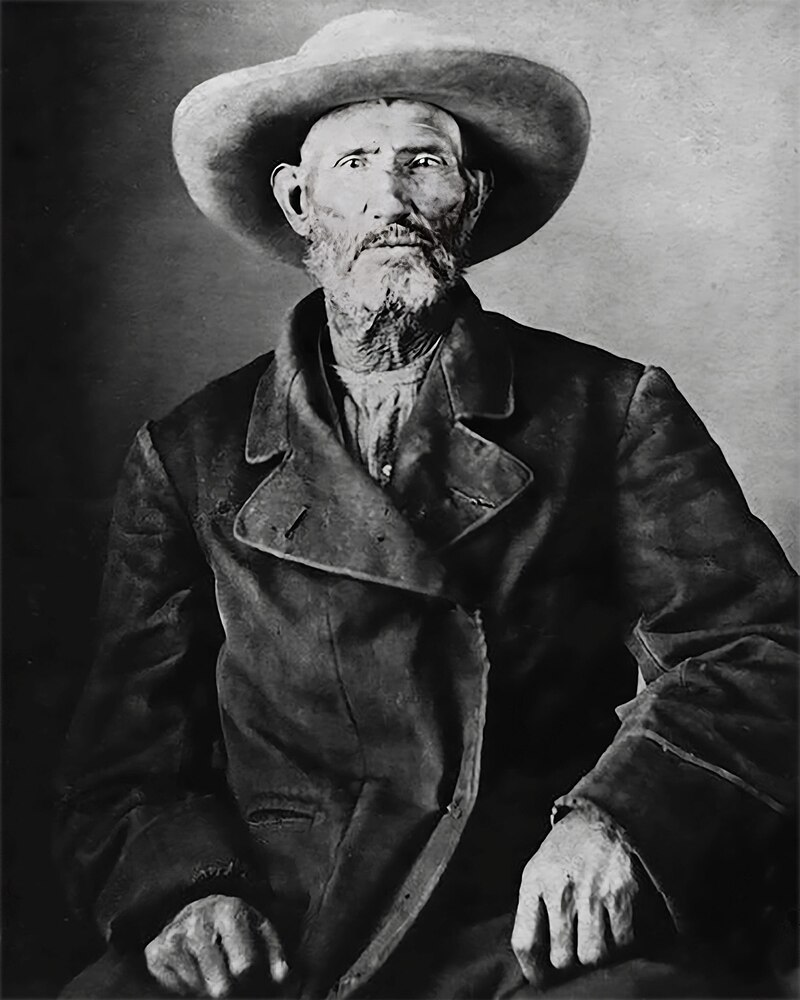

Built in 1844 by “mountain man” Jim Bridger as a trading post on the Oregon Trail.

1804 – 1877

photo circa 1876

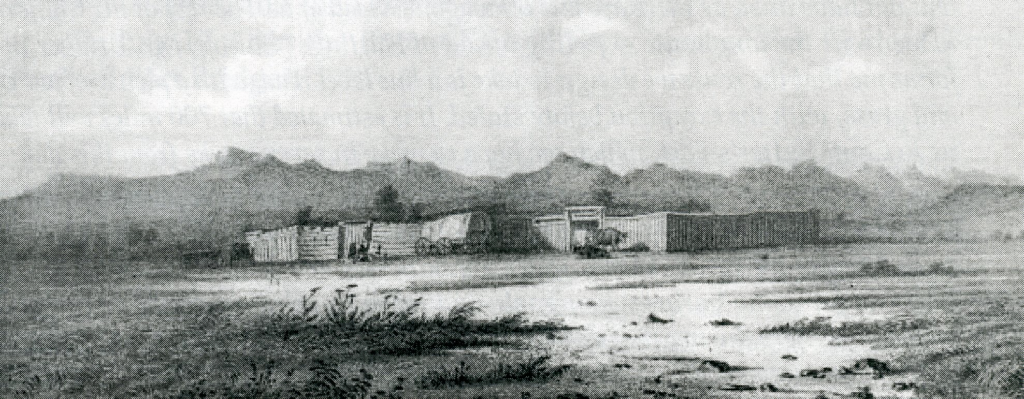

Jim Bridger and Louis Vasquez (links to Wiki page) set up the location in 1843 as an emigrant supply stop along the Oregon Trail. It became a military fort in 1858. The history of Fort Bridger is intimately entwined with the history of western US settlement.

December 1843:

“I have established a small fort, with a blacksmith shop and a supply of iron in the road of emigrants on Black Fork of Green River, which promises fairly.“

It was located about 500 miles from what would become Denver (1859) and 125 miles from Salt Lake (1847) at an altitude of 6600 feet. Surrounded by mountains and built on well-watered green pastures with Blacks Fork passing through, the fort occupied two acres surrounded by a stockade eight to ten feet high. A large log store was stocked with dry-goods, groceries, liquor, tobacco, and ammunition. Bridger’s home was also built of logs within the stockade. A major transportation hub and vital supply point, Mormons, miners, emigrants, military (the site became a military post), mountain men, and Indians all could be found here.

Jim Bridger sold the fort to the Mormons in 1853, who subsequently burned it during the Utah War of 1857/58. It was then transformed into a military outpost in 1858 (until 1890) – keeping the name Fort Bridger – when it was a station on both the Pony Express and Overland Stage. During the Indian uprisings of the 1860s, it was a base for military operations along the mail route.

Fort Bridger remained an active military post until the late 1880’s. When the military abandoned the post, several of the buildings were moved and became private homes, barns, and bunkhouses. In 1933 the state of Wyoming obtained the property. It is now a Wyoming Historical Landmark and Museum.