The Overland Stage: 5 – Julesburg to Junction Station (aka Ft Morgan)

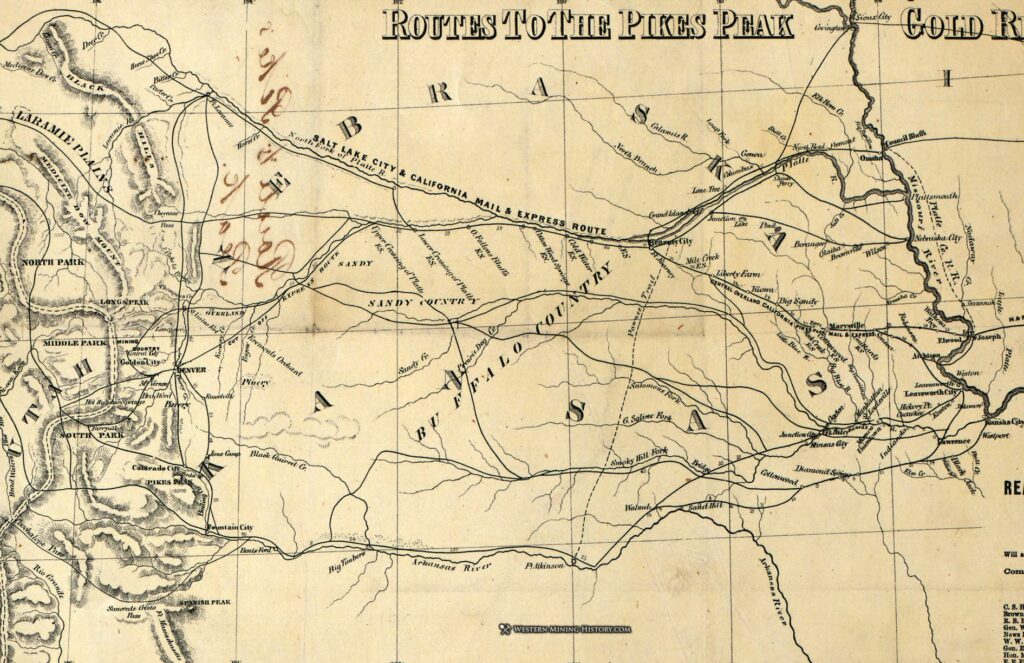

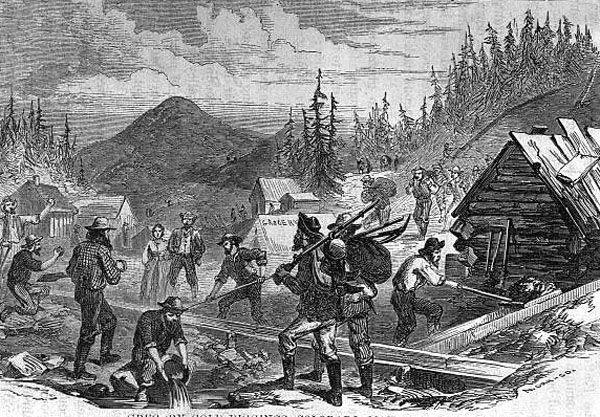

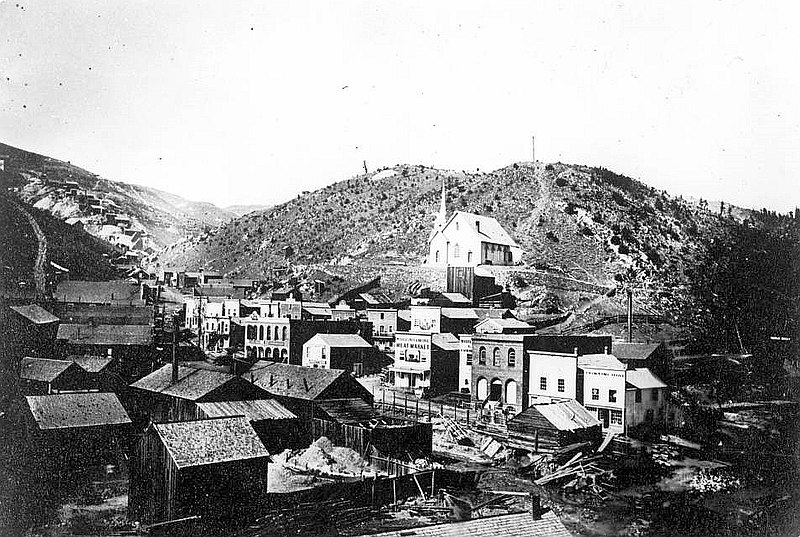

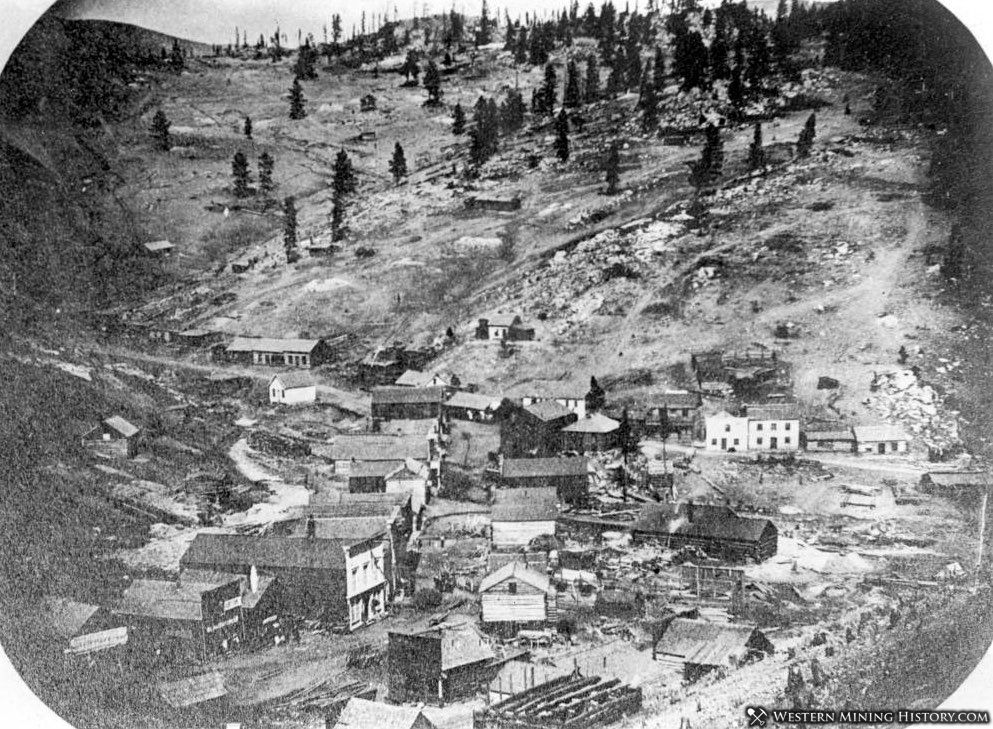

Gold was discovered in what was then western Kansas at Gregory Gulch (Central City/Blackhawk) in 1858, on Chicago Creek (Idaho Springs), on Cherry Creek near the confluence with the South Platte (Denver), and along Boulder Creek (west of Boulder) in 1858/59. The rush was on - known as the Pikes Peak Rush even though Pikes Peak itself was almost 100 miles south. An estimated 100,000 people swarmed to the Rocky Mountains in the spring of 1859.

The early years of the rush centered along the South Platte River near Cherry Creek, up both forks of Clear Creek west of Golden City at Gregory Gulch and Chicago Creek, and up Boulder Creek Canyon. By late 1859, the deposits at Denver, Golden, and Boulder had proven weak but those places became gathering points and supply centers while the deposits west of Golden and Boulder were the center of mining activity - for 20 years or more. The population grew so quickly, it led to the creation of first the unofficial Jefferson Territory, then the official Colorado Territory in 1861 with Golden City the capital of both until 1867 when the Colorado Territory was formed and Denver made capital. Colorado became a state in 1876.

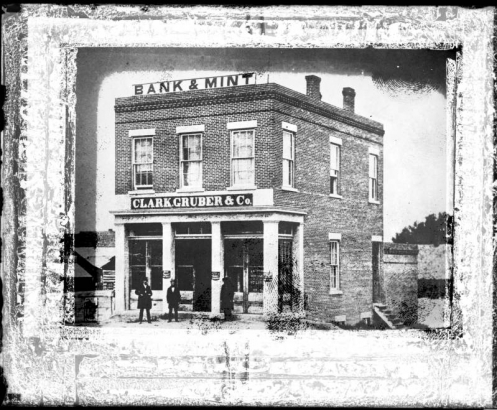

Gold production of the Pikes Peak mining region in 1861 was 150,000 troy ounces (a little over 10,000 lbs) and 225,000 ounces in 1862. By 1865, these districts had produced 1.25 million ounces. Keeping in mind that physical gold was money at that time - officially about $19/oz - and that there was no "central bank", one didn't exchange gold for money - it was money - but using raw gold as a medium of exchange was awkward. The cost of insurance as well as the cost and difficulty due to natural disasters and robbery in transporting gold nuggets and dust from Denver to the Philadelphia mint, then back as gold coins, were the main reasons a private mint - Clark, Gruber and Company - was opened in Denver in the summer of 1860. Miners could deposit gold into the bank and receive a nice return of 10-25% on their deposits. The Gruber $10 gold pieces - containing just shy of ½ oz gold - were minted at the rate of "fifteen or twenty coins a minute". They also minted coins of $2.50, $5.00, and $20.00. (The $10 Gruber coin is now worth over $45,000; uncirculated towards $100,000)

"Letting the eagle fly" referred to getting paid with a $10 coin - referred to as an "eagle". The $20 coin was a double eagle; the $5 coin a half-eagle.

When the $20 gold coin was added, the company declared "the weight will be greater, but the value the same as the United States coin of like denomination". Production reached $18,000 per week but the coins of pure gold were too soft, so an alloy was added lowering the gold content somewhat. By 1862, Congress allowed the formation of a new US Mint in Denver; it opened in late 1863.

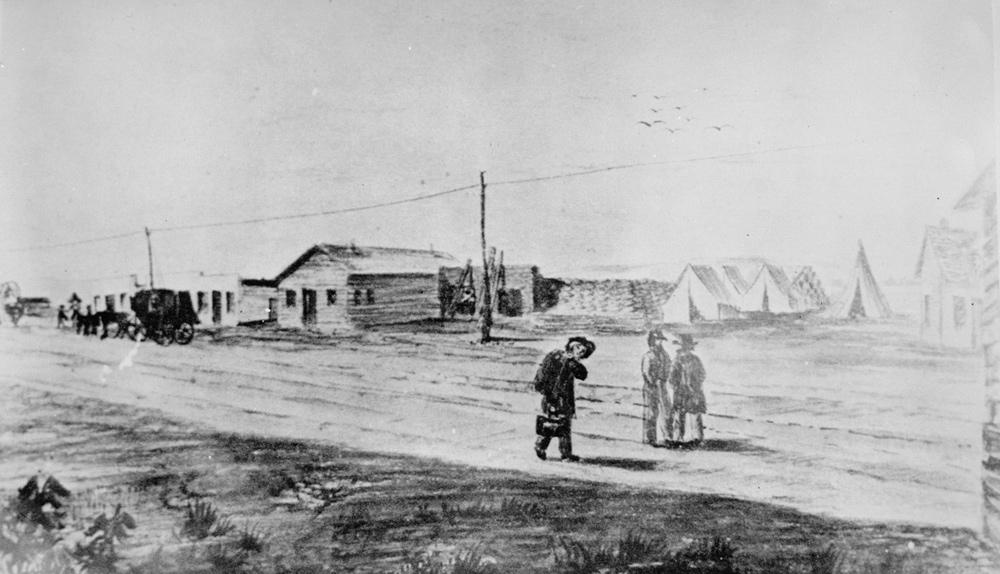

The Overland Stage Company provided transportation services for such cargo, as well as for passengers and other goods. In the earliest days before the rush, there was no "Denver" to speak of - settlements such as Montana City, Auraria, St Charles - were the "towns" of the region; the name Denver was given to St Charles for political reasons; named after the governor of Kansas as the capital of the western-most Kansas county. The gold deposits in the region were sparse down on the flats - the mines were west up in the foothills. Rather than fading away like the other small settlements in the area, Denver's location on the South Platte made it an acceptable site for a supply center.

The original South Platte River Route left the Platte just east of what is now Greeley and headed NE along the Cache la Poudre on the road through the Laramie Plains, over Bridger Pass to Ft Bridger via Bitter Creek, and on to Salt Lake City. However, with the mining boom and associated traffic, Denver grew quickly and a route to "the diggings" - continuing down the South Platte with the main stage station located at Denver - was established. Traffic along the South Platte became the heaviest along the entire line.

There was no "Denver" in late 1858

Central City was up the canyon

Both towns exist today - much changed - as tourist/casino centers

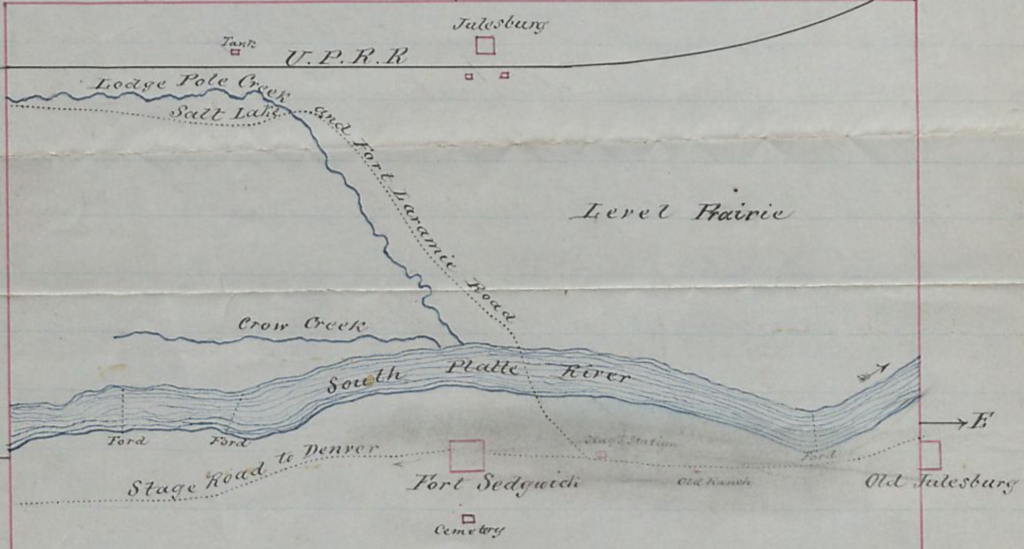

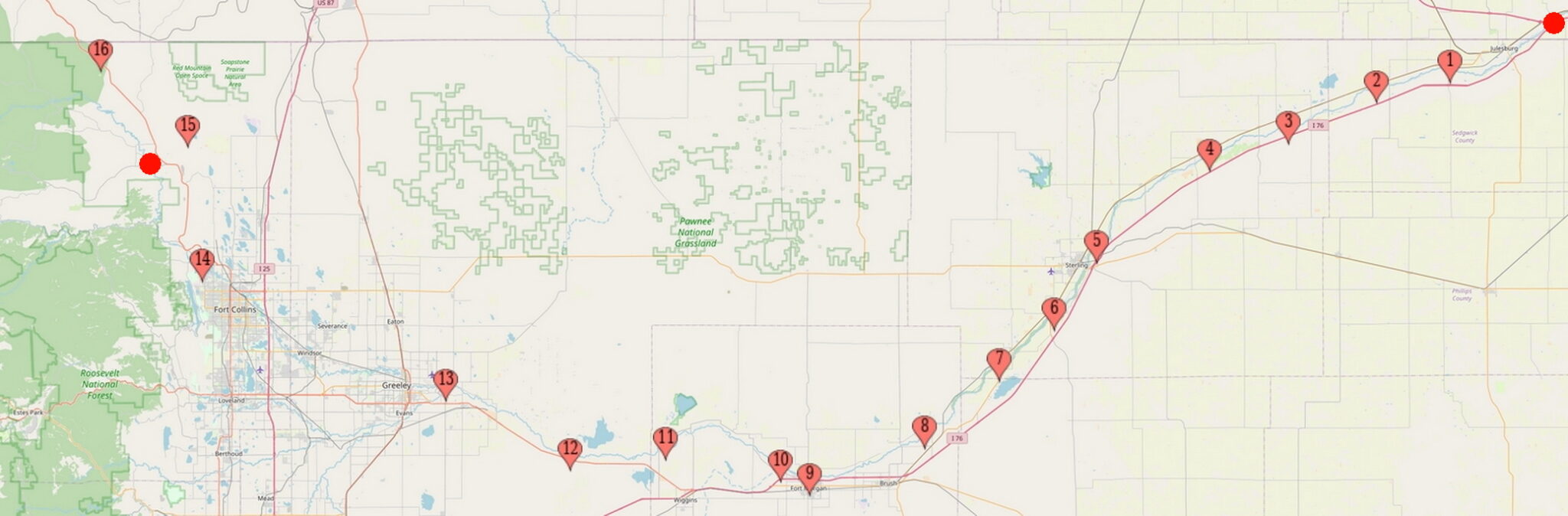

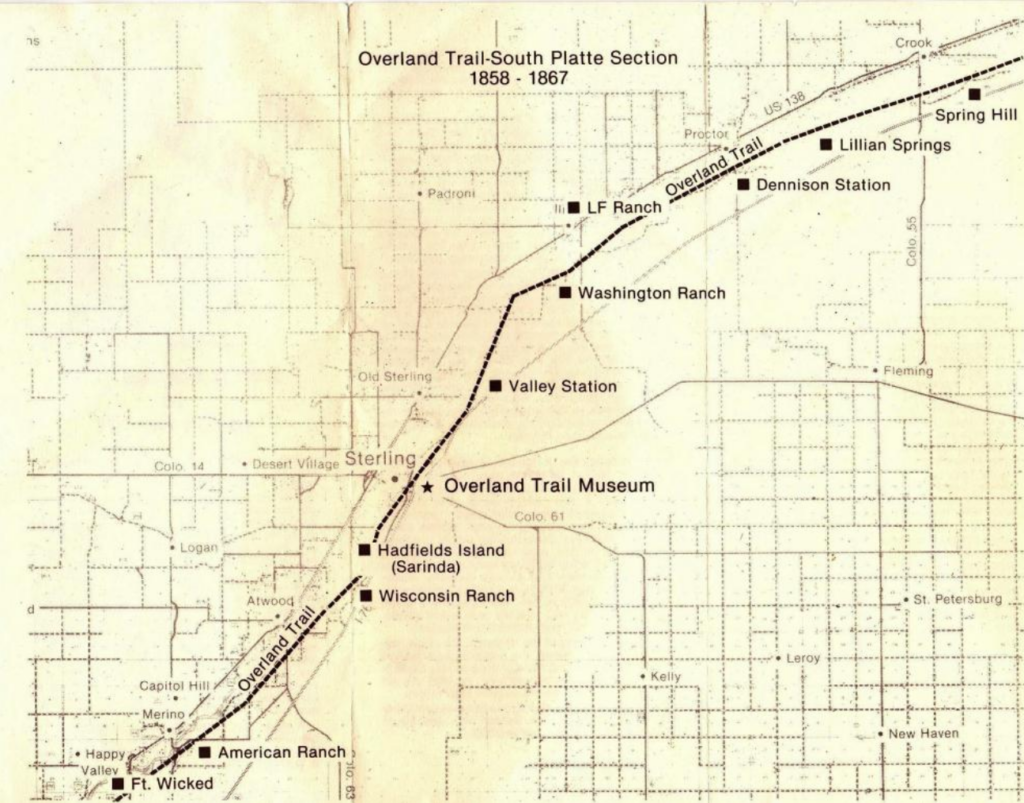

The South Platte River Route - Julesburg to Lanham

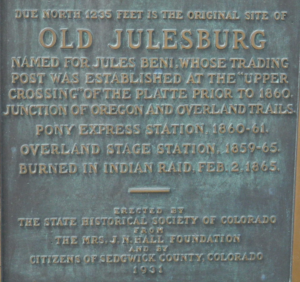

Little is known about the next several stations upriver from Julesburg. It is likely most were simply ranches - swing stations - which provided a place to change teams with no facilities for passengers. Most were burned out by Indian attacks in early 1865; not all were rebuilt. Wells-Fargo took over the line in 1866.

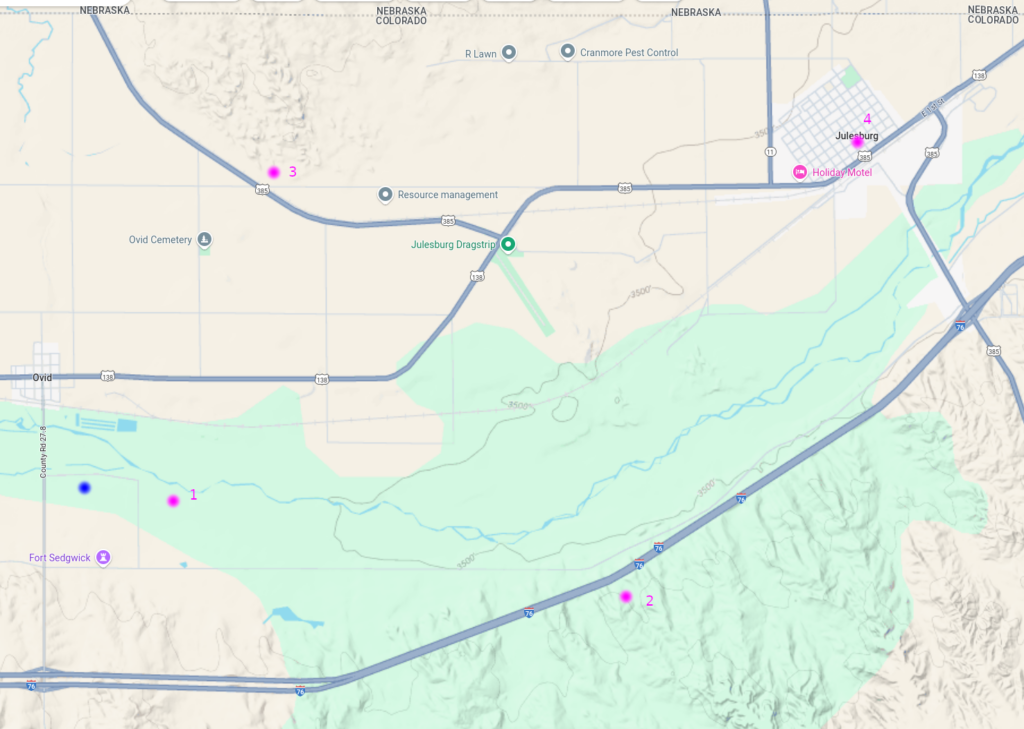

South Platter River Route - Julesburg (point 1) to Latham (point 13): 136 miles

including South Platte station and the section from Latham to Virginia Dale: 61 miles

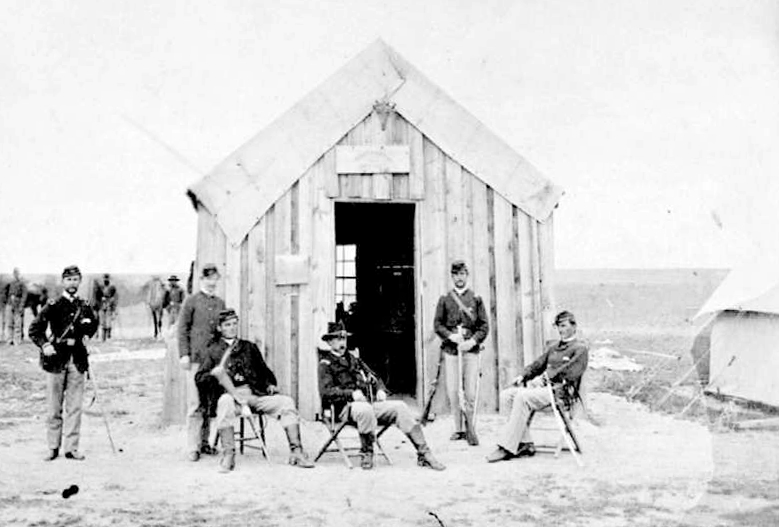

By 1863, the increased traffic in people, valuables, and the mail, caused the Army to plan on establishing several forts along the road, assuming this would provide the most effective protection. However, it wasn't until the summer of 1864 before such action was effective when 1,000 troops were sent to patrol the Platte River Road and set up outposts. Four sites were located, Camp Rankin - later Ft Sedgwick - near Julesburg, among them.

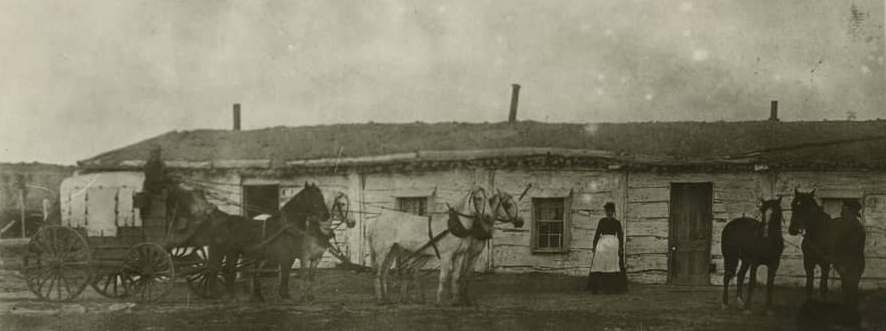

The Valley Station near what is now Sterling was taken over for military use. Camp Tyler was set up near Bijou Creek; later renamed Camp Wardell, then becoming Fort Morgan. Camp Collins - later Ft Collins - was built along the Cache la Poudre River to protect westbound travelers on northern stage roads. Camp Weld, just north of the current US6/I-25 interchange in Denver, was used as a base and supply depot for the regular Army. These forts were constructed of sod and adobe rather than having wooden stockades.

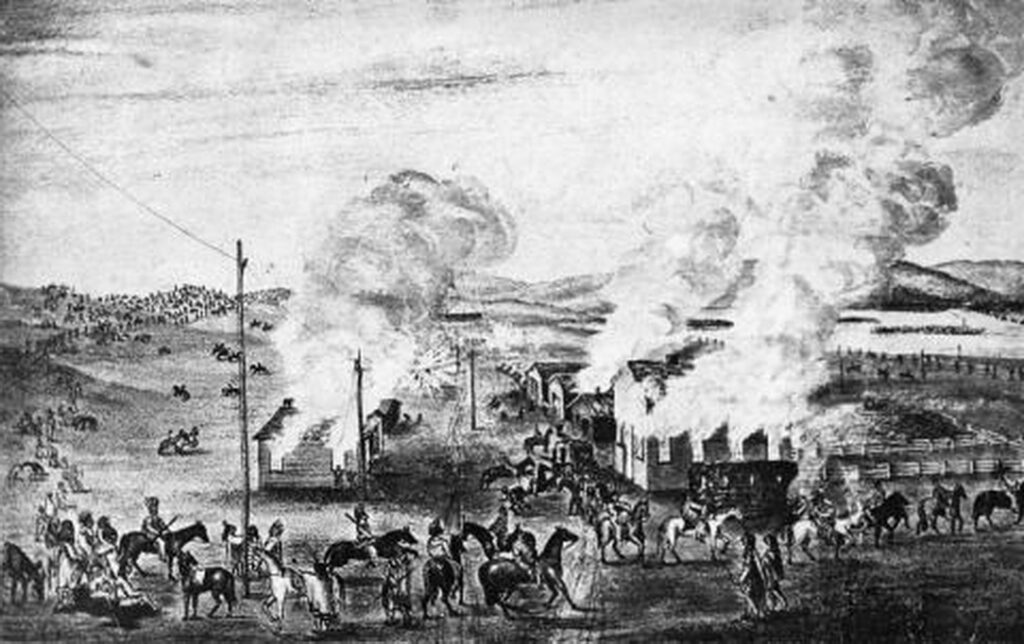

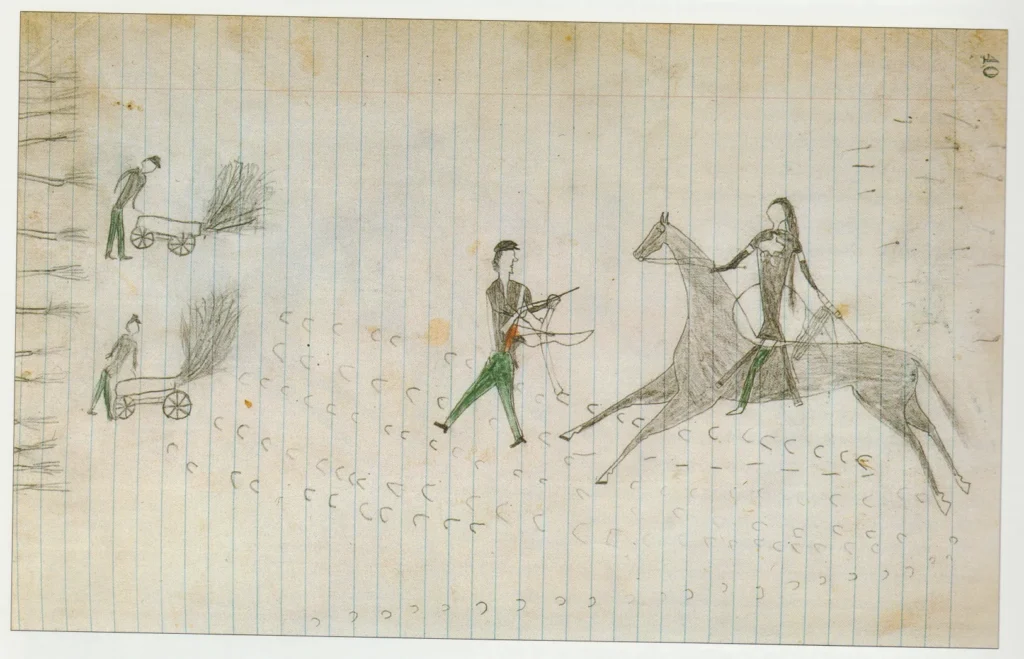

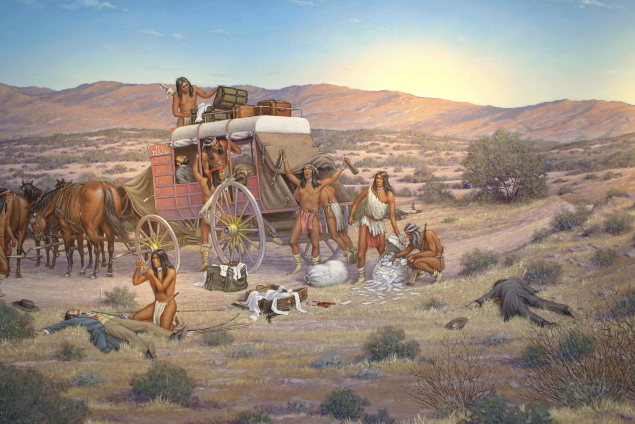

Although Indian relations at the beginning of stage operations were relatively benign, the Sand Creek incident in late 1864 enraged and unified the various Indian tribes of the region - mainly Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Sioux -inciting a desire for revenge. The attacks started in January 1865, when Julesburg was first raided. A second attack in February burned out the town. More attacks spread down the South Platte as marauding Indians attacked stage stations and ranches. Travel along the route became dangerous and was halted for a time in 1865.

During the war back east when manpower for western operations was low, the Federal government offered Confederate POWs "freedom" in exchange for moving to multiple frontier posts, including those in NE Colorado and Wyoming. The now ex-POWs were required to swear an oath of loyalty to the US, then were enrolled into the Union army to serve in western outposts. These soldiers were nicknamed galvanized Yankees, referring to a galvanizing process which stopped iron from rusting. "A few days of terror surrounded by months of boredom" pretty much described a soldier's life on the frontier. Garrison and escort duty led to low morale; alcoholism and drug addition (opium) became problems.

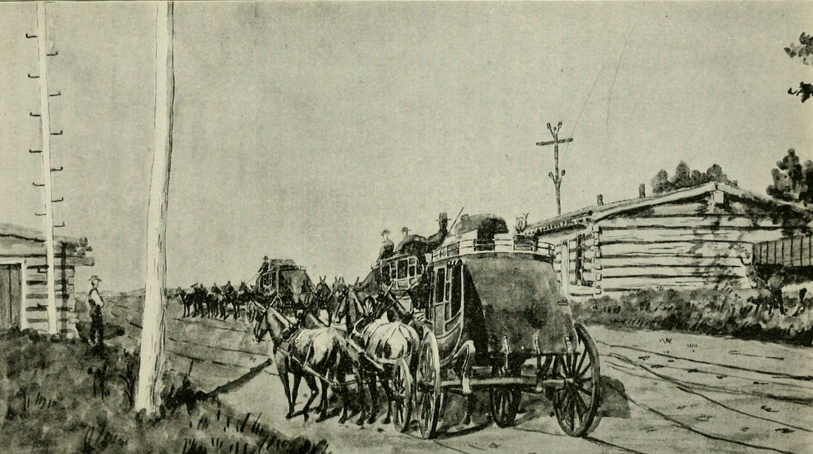

Peaceful farmland for the most part today, it's hard to imagine the desolation along with constant fear of Indian attack along the South Platte of the 1860s. Population of the entire region was only in the low hundreds, if that - many being stage employees. Travelling along essentially the same route (Julesburg to Latham - 150 miles) on I-76/CO14/US34 "where wagon drivers cursed the endless sand and the insects and the heat of the treeless river bottom" now only takes 2.5 hours or less. In the days of the stagecoach, such a journey might take 18-20 hours or more - maybe days, depending on several factors - weather, Indians, road conditions, breakdowns.

Times change.

Indians are no longer a problem, but road conditions, breakdowns, and weather are still possibilities - this is blizzard and tornado country.

.

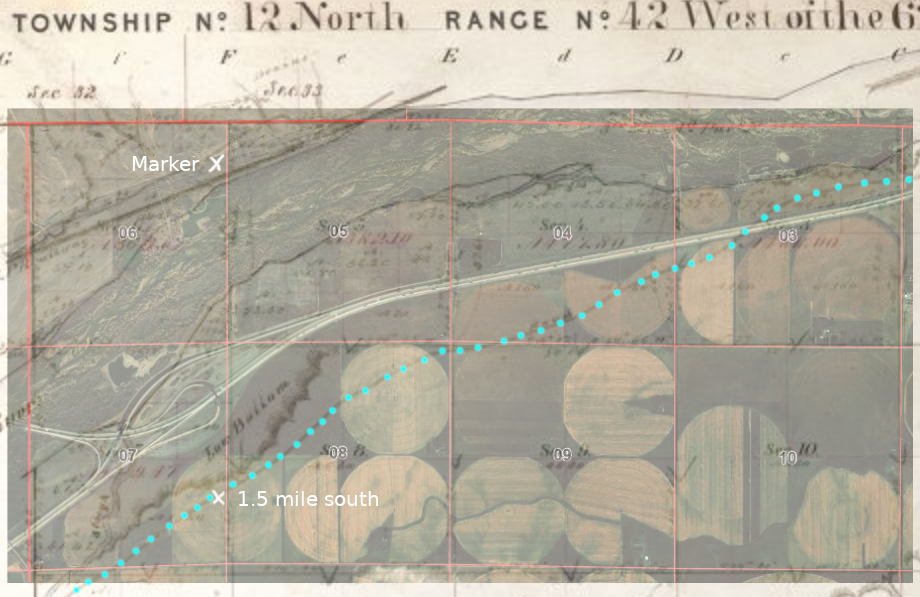

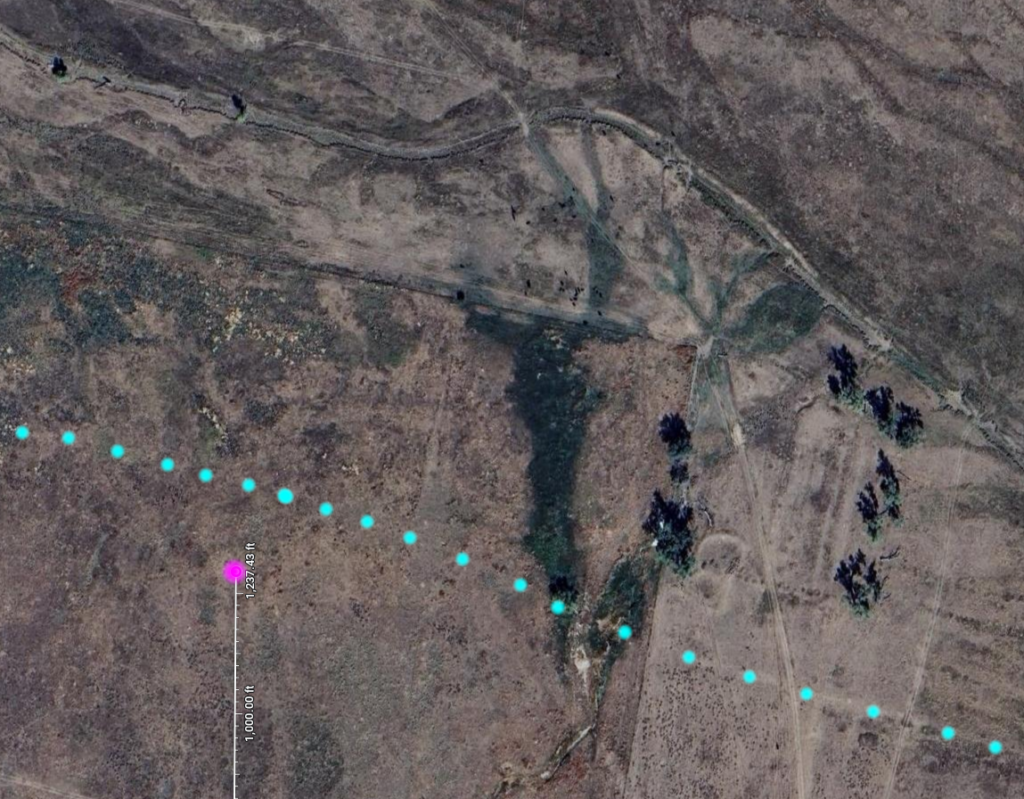

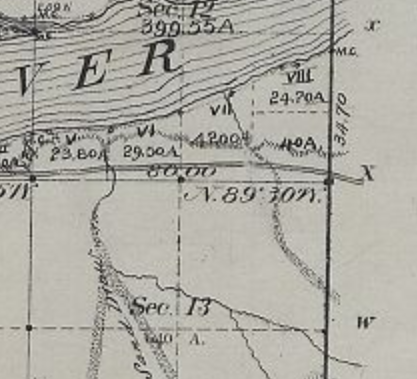

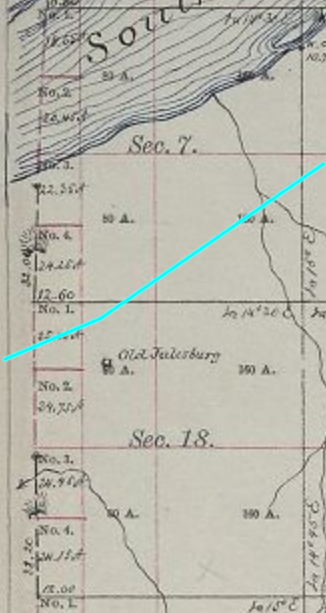

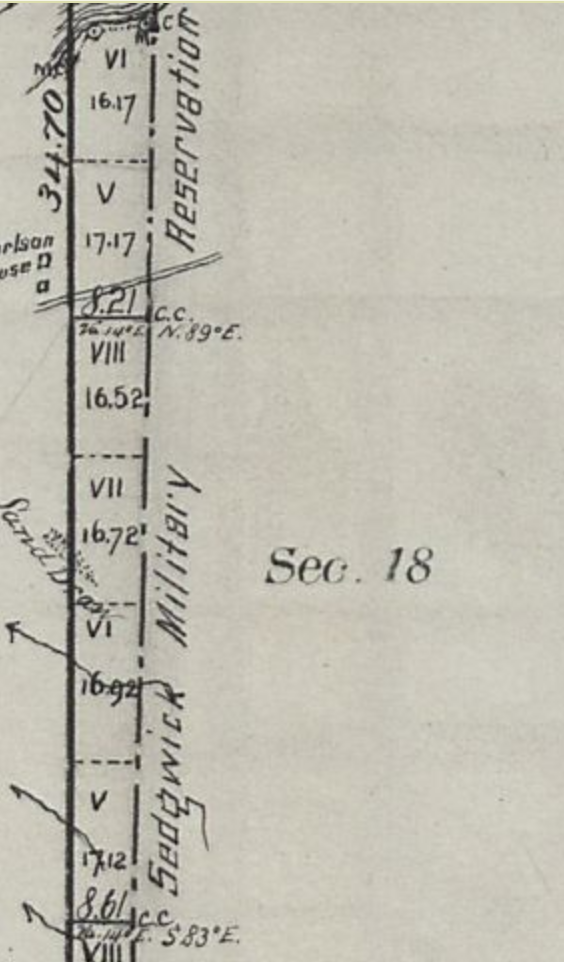

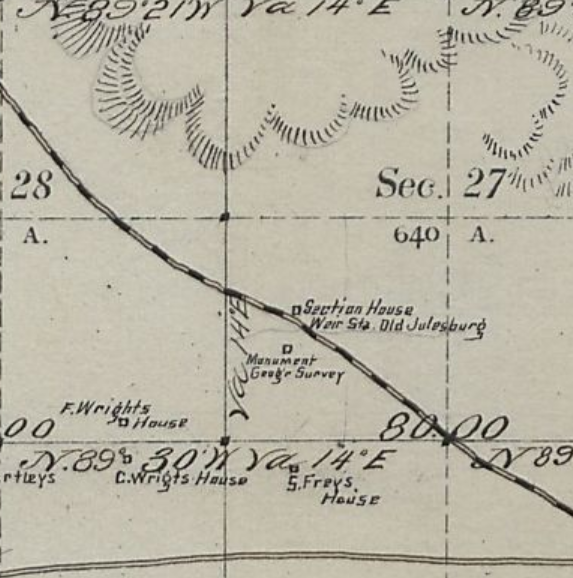

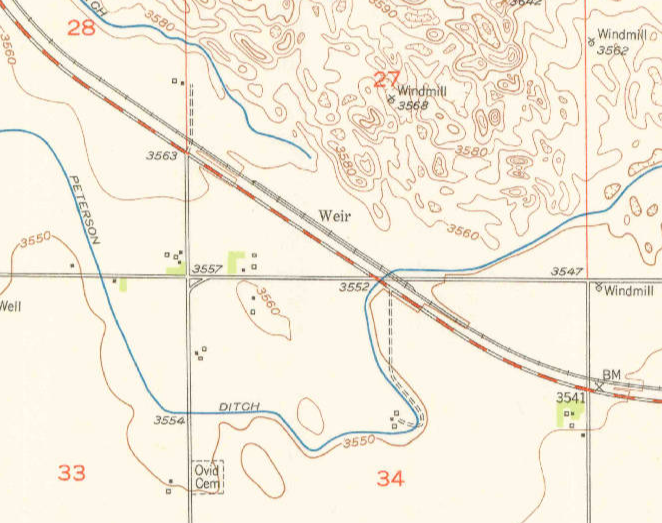

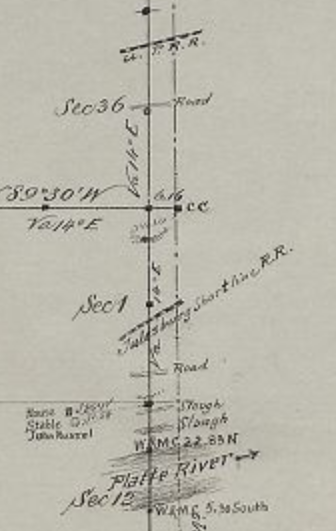

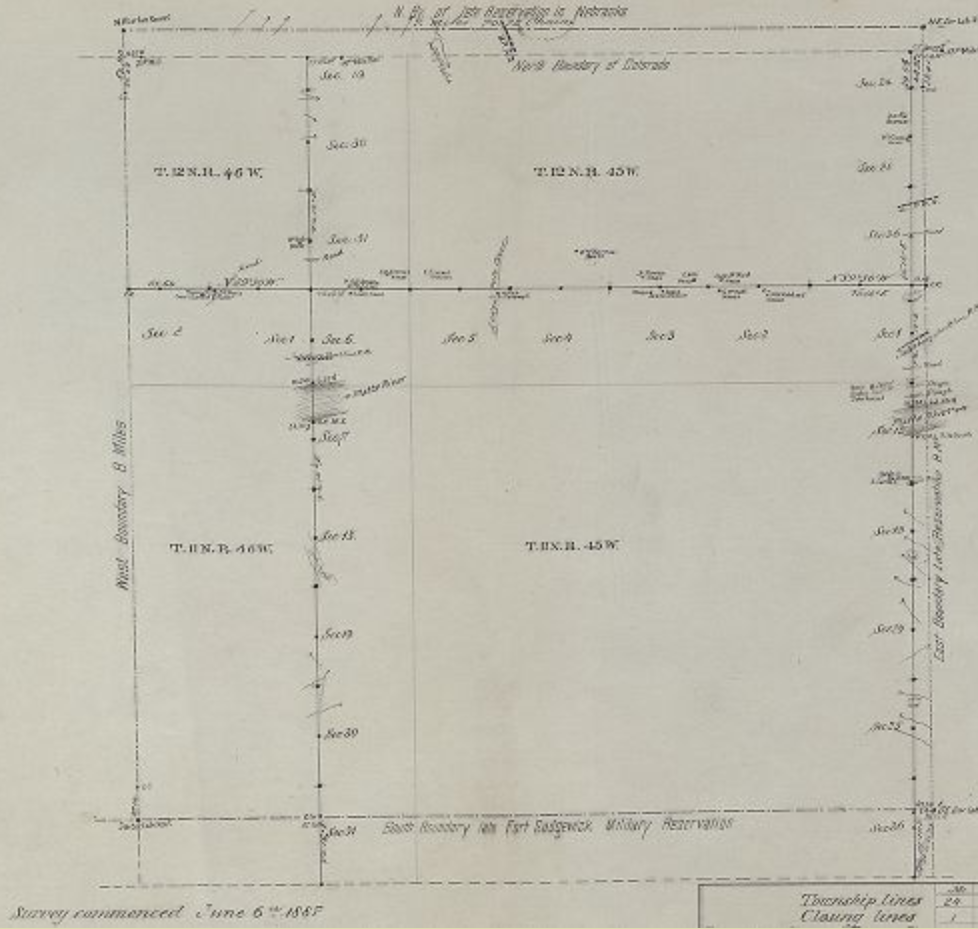

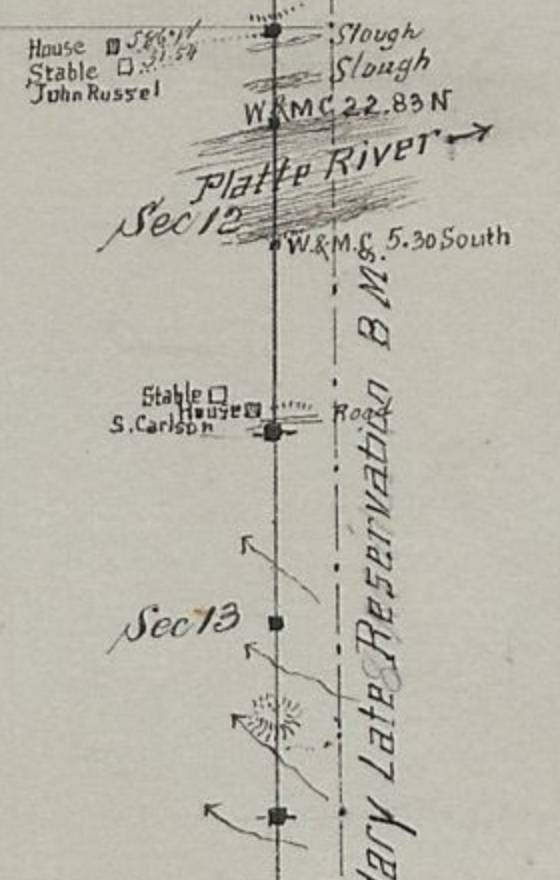

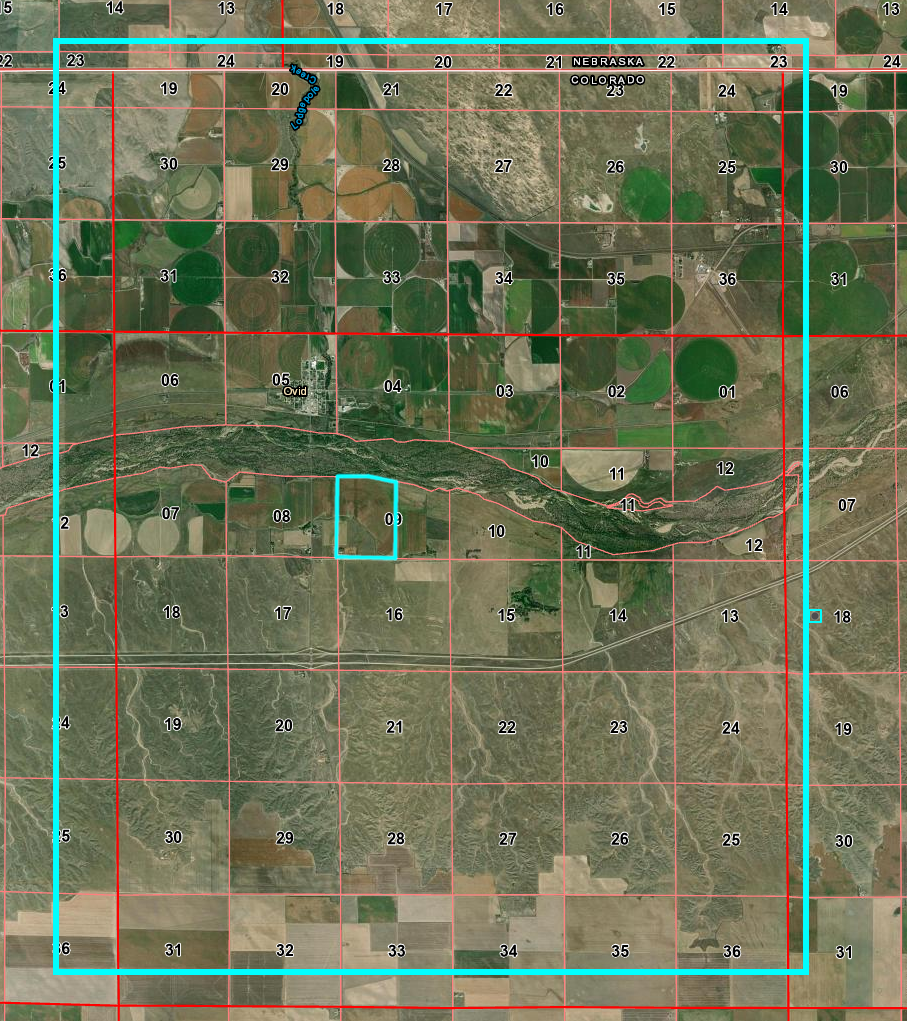

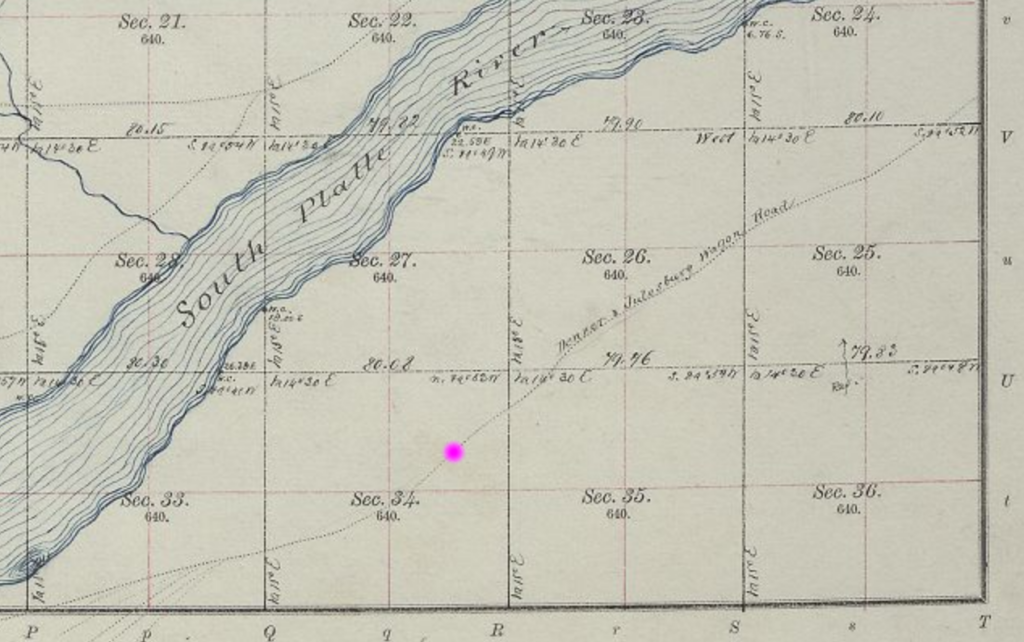

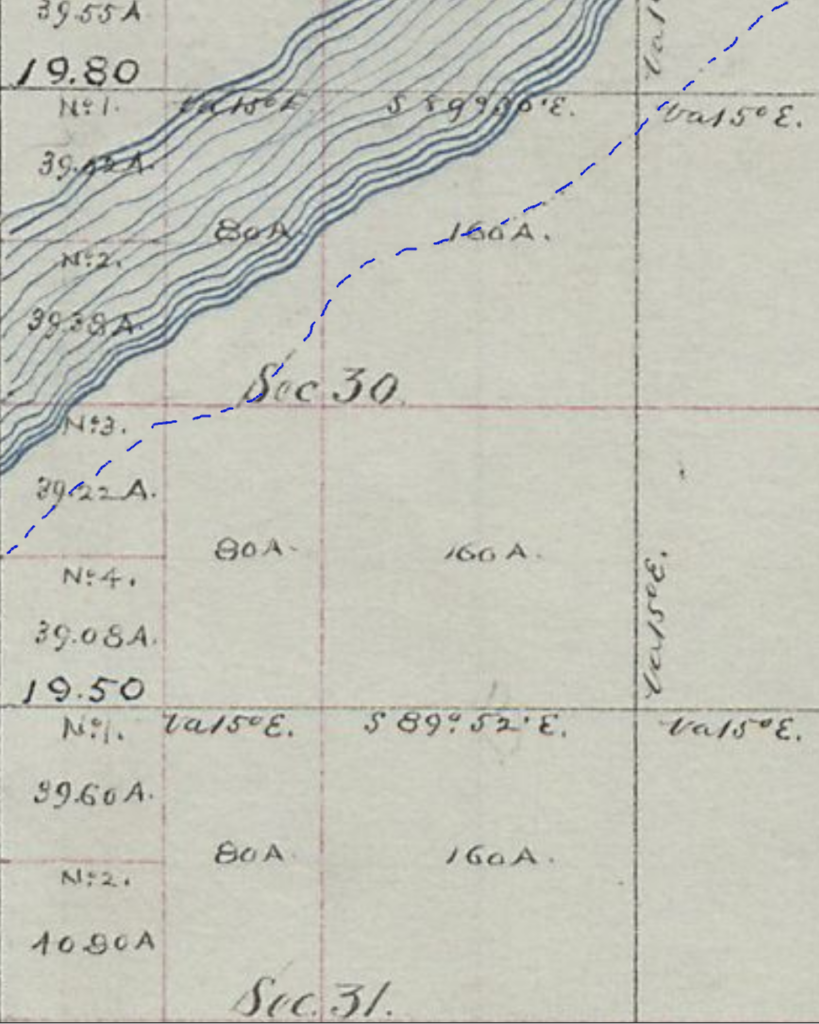

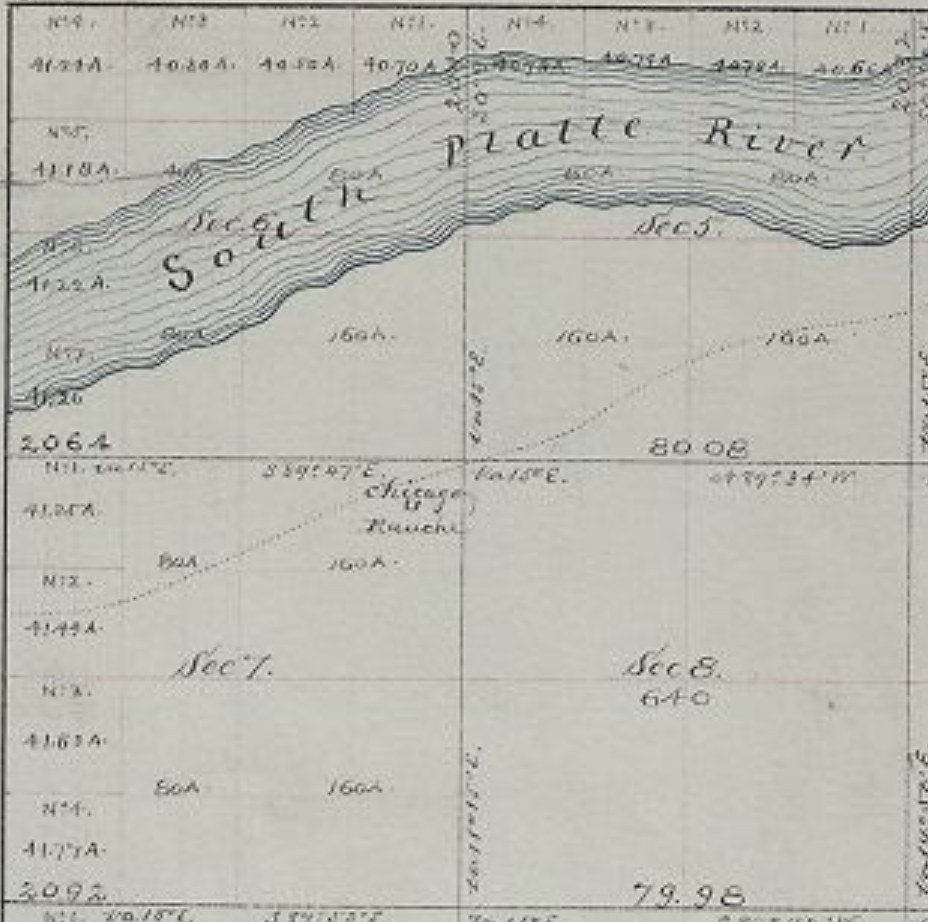

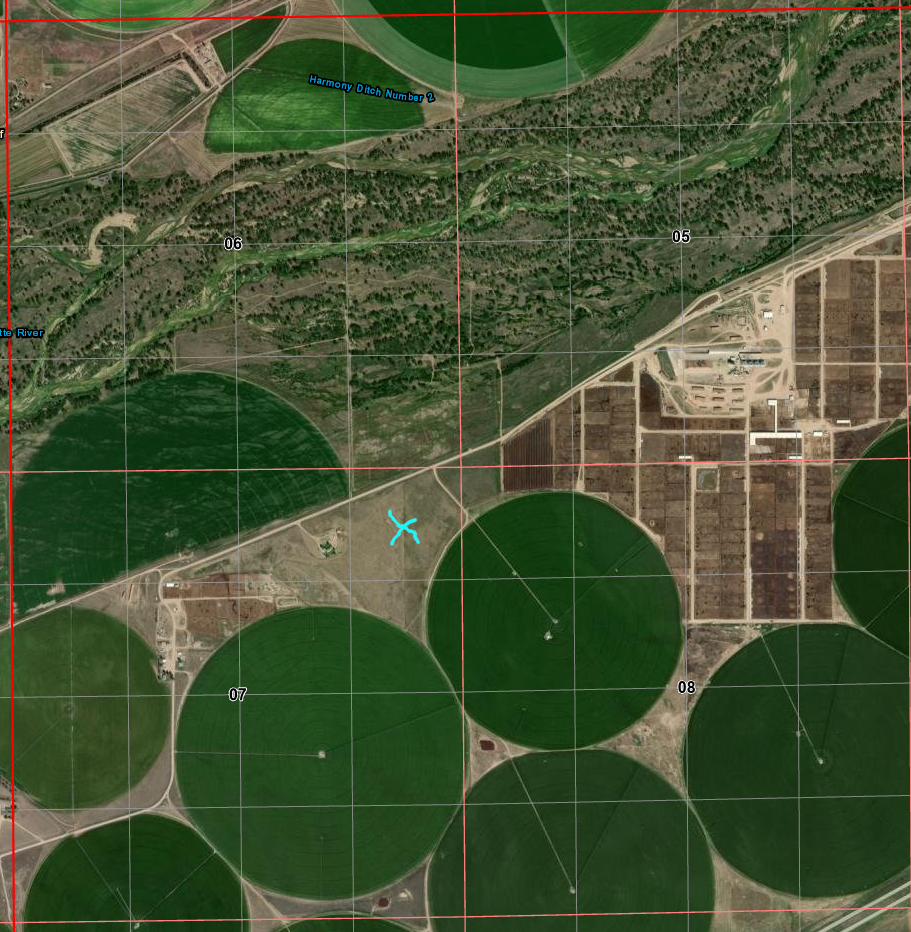

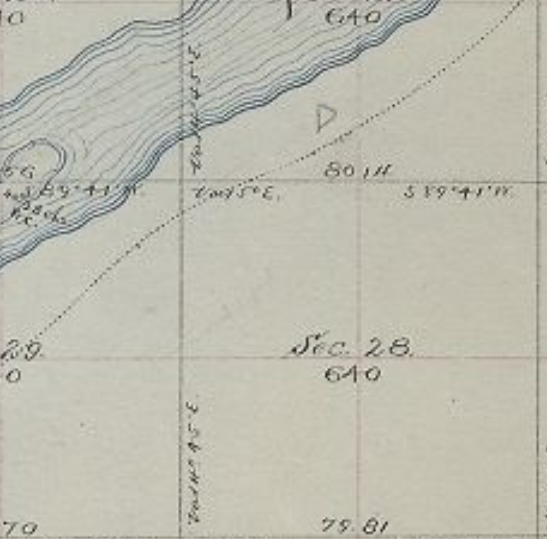

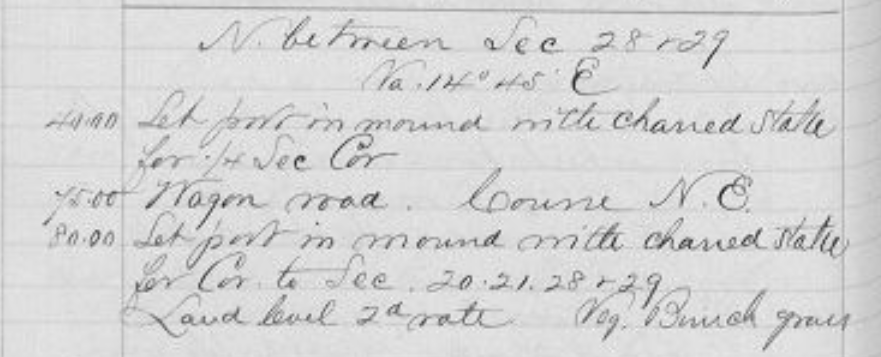

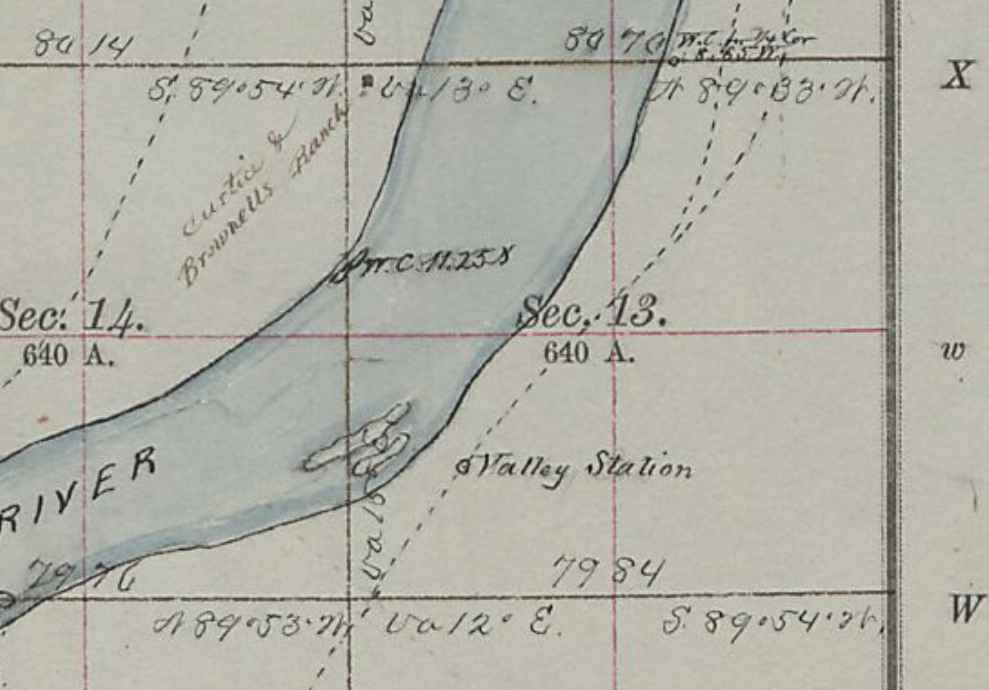

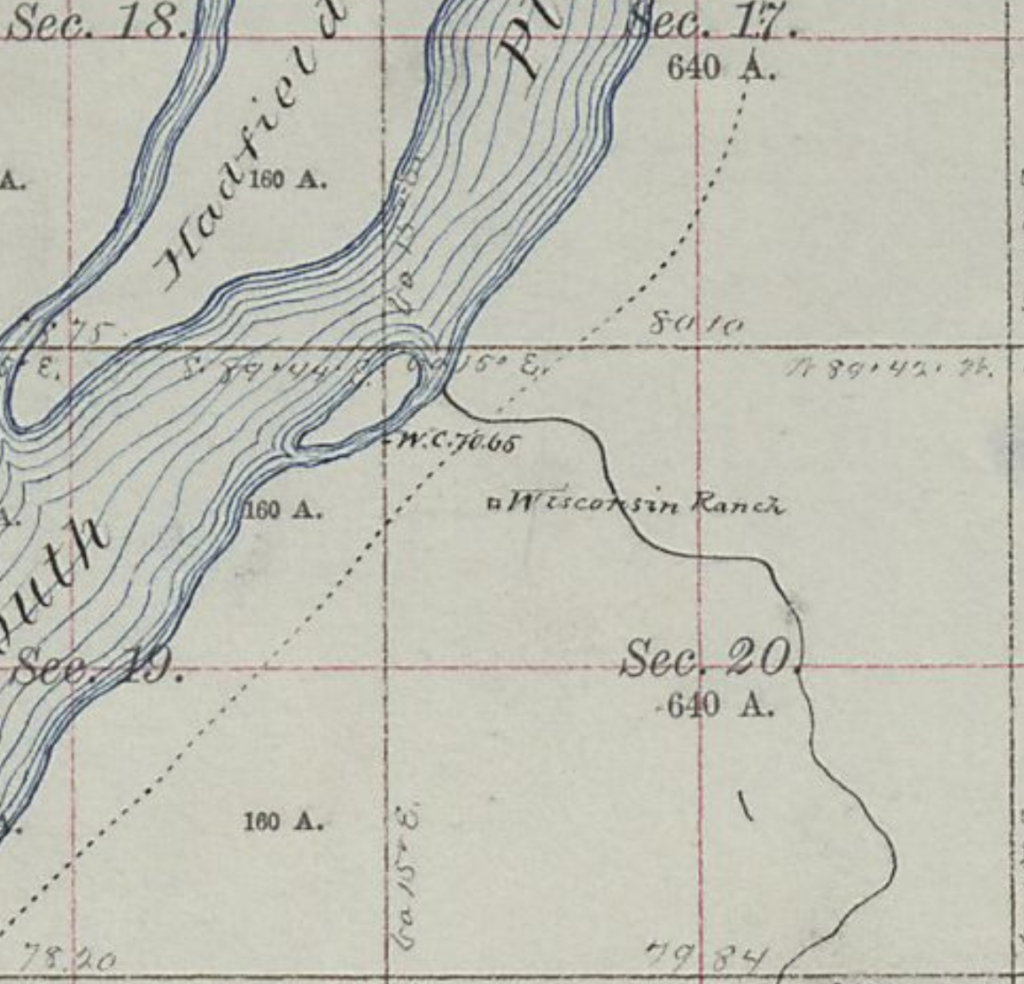

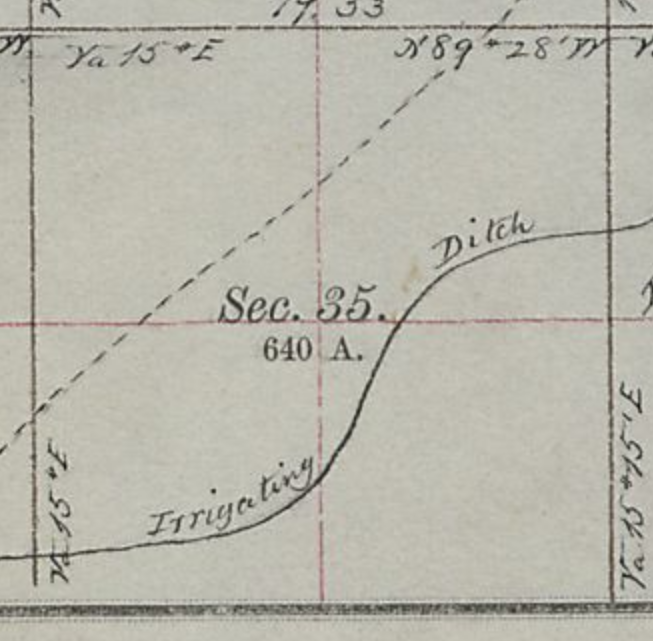

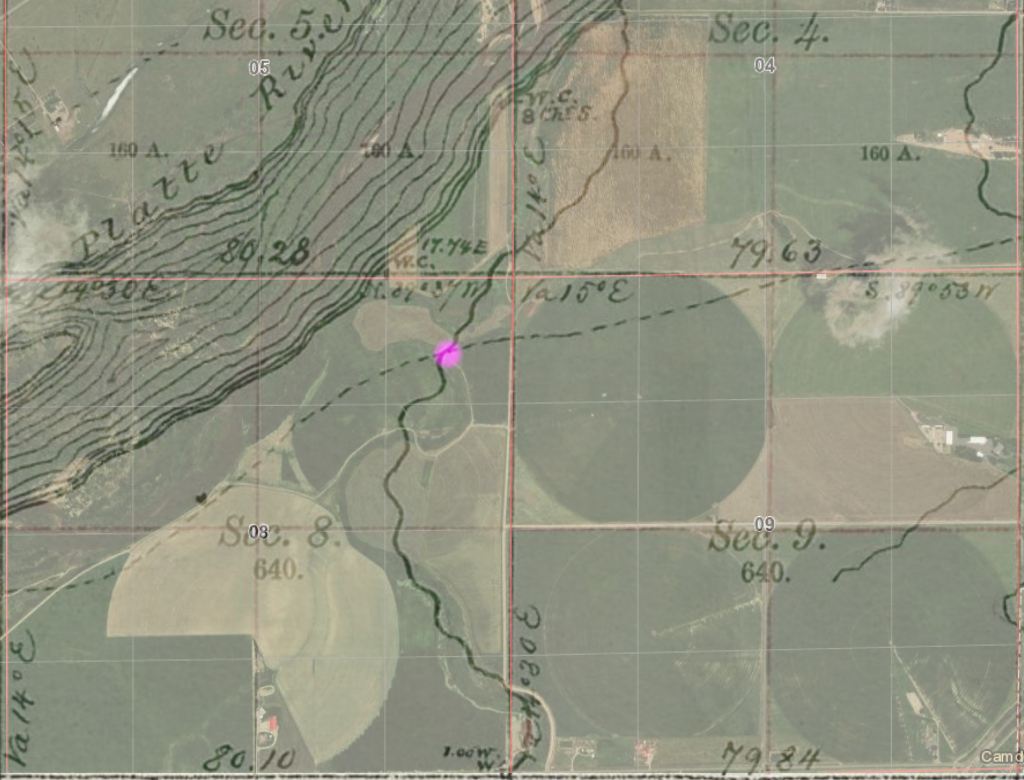

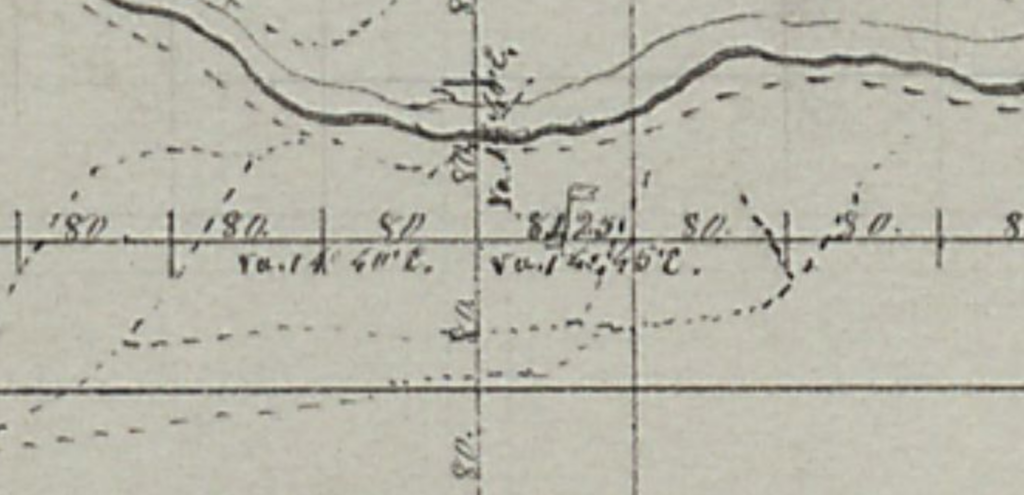

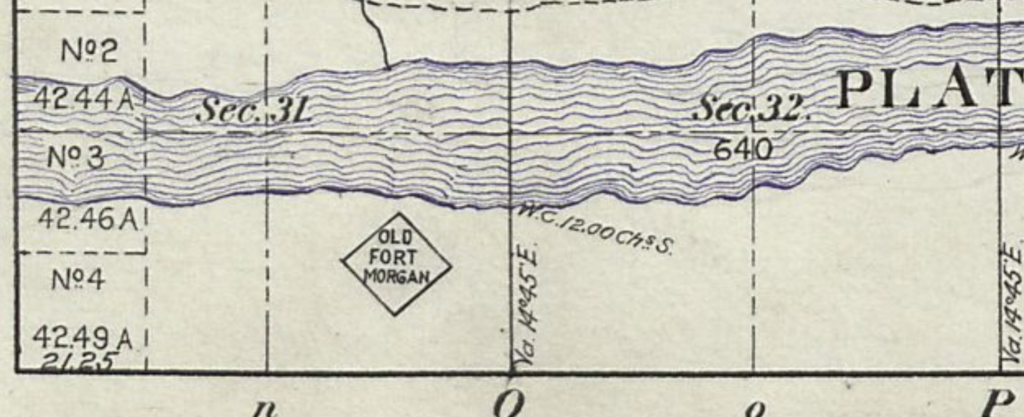

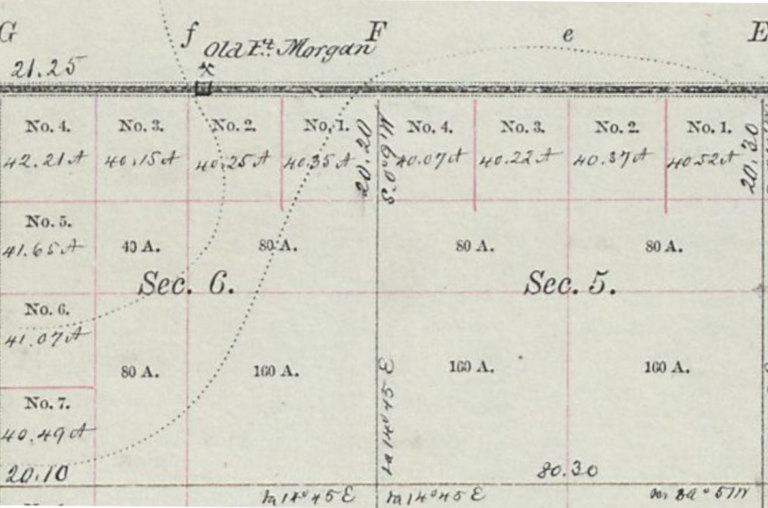

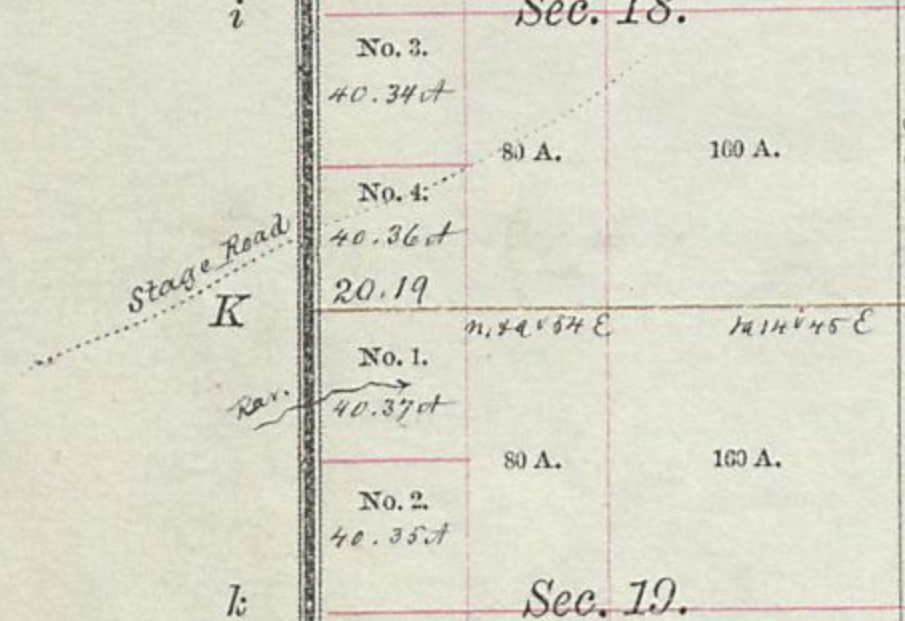

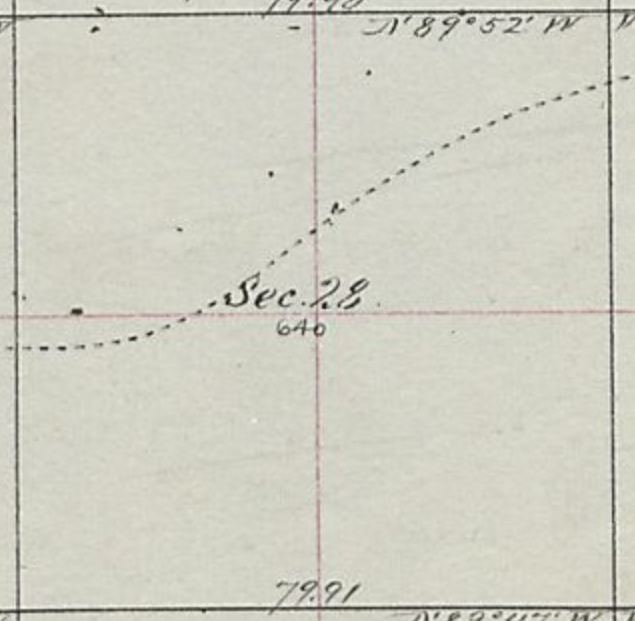

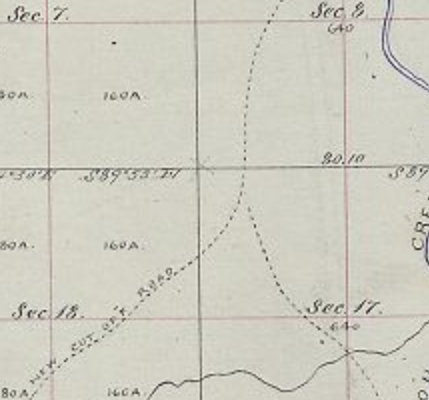

The region was formally surveyed during the period towards the end and just after the time of the Overland/Wells-Fargo stage lines - about 1865 - 1873. The surveyors mapped out the territory, carrying their equipment in wagons. Sections of those maps are shown to show the trails were the stagecoaches ran. Not all the information desired is indicated - most, not all, station locations are not included. By the time of the surveying efforts, they had mostly been destroyed, abandoned, or turned over into ranches - or just not important to the survey efforts.

possibly 10N48W corner 18/17/19/20

West from Julesburg

Eleven miles west of old Julesburg, along a somewhat rough road, was Antelope ; and thirteen miles farther was Spring Hill, a "home" station, kept by Mr. A. Thorne; thirteen miles farther was Dennison's; and another twelve miles brought us to Valley, also a "home" station. Fifteen miles farther was Kelly's (better known as "American Ranch"); and Beaver Creek was twelve miles farther west. Then came the longest drive without a change of team on the road between the Missouri and the Pacific. It was Bijou, twenty miles from Beaver Creek; there being no suitable location between the two stations for another one. To go over this long drive, where there was considerable alkali and sand and a number of sloughs, required some of the best teams on the entire line, and there were extra teams, so that all in turn would have a day's rest and none of them be overworked.

Antelope Station

11N47WS35NWNW

40.89439201370095, -102.5727573854817

County Rd 22 goes past the approximate site

40.90183013712542, -102.58533271845896 11

40.88351881577574, -102.61680143036618 13

Antelope Station was the first station upstream from Julesburg. somewhere 11-13 miles distant, it was burned out in January 1865

Antelope site marked at 12-mile point; could be a mile either direction

actual location perhaps 1 mile either side - (one section is 1 mile on a side)

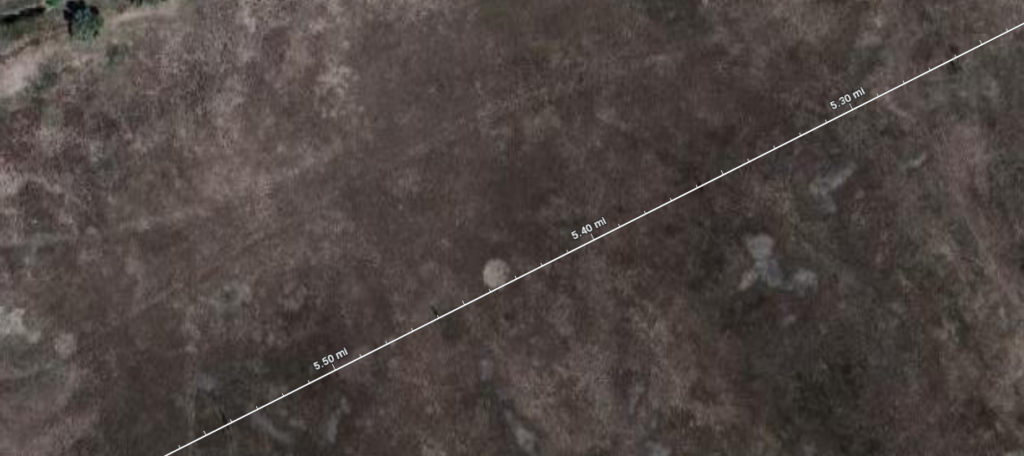

In areas not under irrigation, there are faint traces of what might be remnants of the trail - or imagination seeing things no longer present in places where such things may have been at one time. Such questions make the search interesting.

1865, Jan. 28

Antelope Station was burned out in January, 1865, including a house of two rooms, a barn, and a corral; all the buildings, valued at three thousand dollars, along with 25 tons of hay and 125 sacks of corn were burned during the Indian raids. After the buildings were destroyed, the Indians spent the rest of the day hauling provisions from the storeroom back to their camp. They loaded up their poledrags with bacon, ham, flour, sugar, molasses, and even oysters.

Comparing the 1872 maps with today's, it appears the station site has been plowed under - if indeed this was the station site.

"An Overland stage station occupied by the CO Cavalry. Undetermined location, more than 10 miles from Fort Sedgwick. Attacked and destroyed by Indians in January 1865."

not quite 1/2 mile out between "here" and the trees in mid-distance (the river)

based on 1871 map of road and distance from previous station

Spring Hill/Lillian Springs

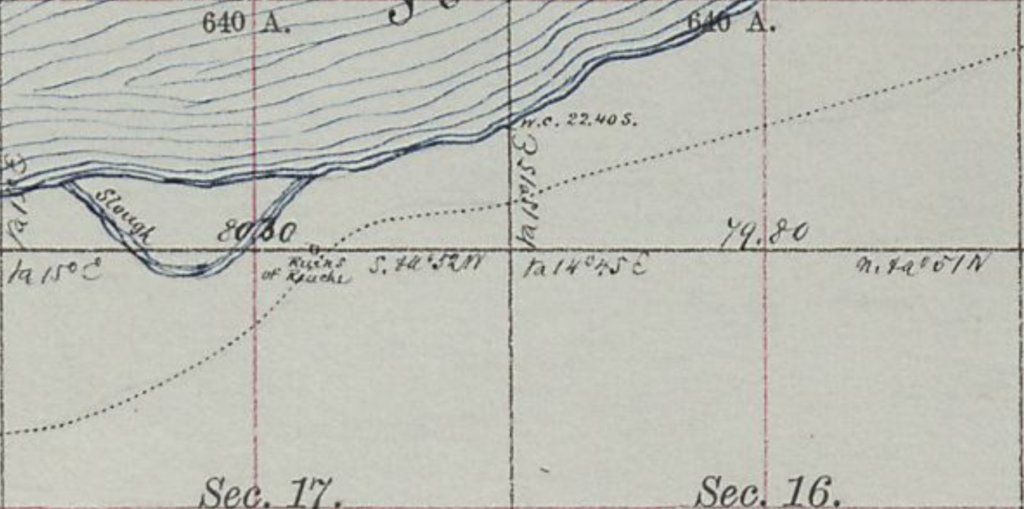

Neither of these stations is well located; site locations estimated from information on this historical marker and evidence on aerial photos.

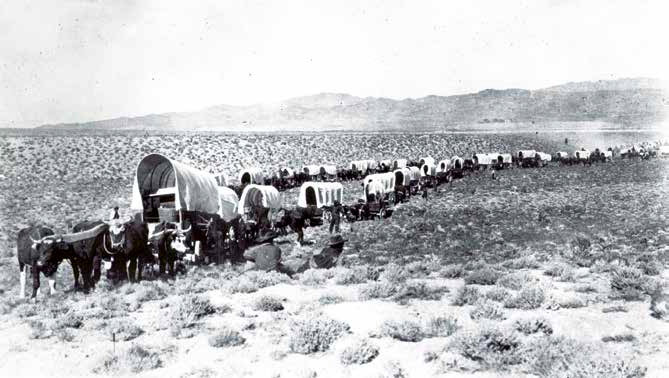

Often there could be seen a string of four- and six-horse (and mule) teams and six to eight yoke of cattle hauling the biggest heavily loaded wagons. Frequently a train a mile long might be seen on the road. Many times a number of trains could be seen together, and the white, canvas-covered vehicles extended for many miles, or as far as the eye could see. were the ox trains of Russell, Majors & Waddell, of Leavenworth. Their ponderous wagons were made to order in St. Louis and built so they could carry from 5000 to 7000 pounds of merchandise.

Spring Hill

10N48WS09

40.85090355294632, -102.73714562628182 based on ruins located on 1871 map

or: 40.85613444290205, -102.71466751842938 based on historical marker

roughly 1 mile apart

The Spring Hill location was a "home station" - one that provided food and took on passengers. It was a new station in 1860 but in an indefensible location. It was reported to have been one of the best along this section of trail, valued at over six thousand dollars. It was destroyed on January 28, 1865

Harlow's Ranche was burned, and three men were killed and a woman was captured; Buffalo Springs Ranche was burned; Buler's Ranch below Julesburg burned; Spring Hill Station, a home station, burned including dwelling house of four rooms, barn, and furniture; 500 cattle were stolen and 100 tons of government hay burned at Moore's Ranch. Dennison's Ranche burned. The Indians camped between Moores Creek and Twin Buttes from January 28 to February 2 and raided every day.

Picking the site based on the highway marker, the station is located only about 8 miles from Antelope. However, the distance works if considering Lillian Springs. At some point, Lillian Springs is reported to have been replaced by Spring Hill, yet both are described as having been destroyed by Indians in 1865.

A bit of discrepancy here: Antelope is 13 mi from Julesburg based on Overland mileage logs - this works for the original Julesburg. Spring Hill is 13 miles from Antelope. However, Spring hill is 5.2 miles east of CO55 (to Crook) according to the marker. This works out if measured from "now" Julesburg 4 but not from original Julesburg 1.

The 1871 map shows ruins at "proper" location for Spring Hill based on mileage.

Julesburg 4 is about 6 or 7 miles east of the original Julesburg stage station. Could it be later chroniclers confused stations?

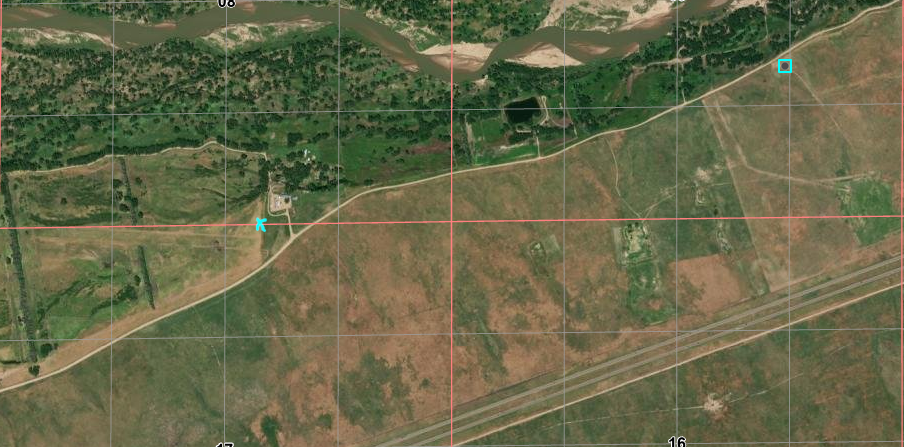

Both potential station locations are indicated; the x by the ruins on the 1871 map; the square suggested by the historical marker.

The diagonal path across the bottom is I-76

Lillian Springs (aka Sand Hill Springs)

approx 40.81170873093629, -102.8779128175366

10N49WS30SWNE

Location estimated by measuring distance from historical marker

This station was built in the summer of 1859 - the year of the gold discovery. It was used by three stage companies: the Leavenworth and Pikes Peak Express was reorganized early in the 1860s as the Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express Company (COC&PP), followed by the Overland Stage Company after the former firm went bankrupt. Lillian Springs was the primary station until the Spring Hill station was built in 1860. A post office operated here for 9 months from summer 1863 to spring 1864. It was among the stations destroyed by Indians in 1865.

near Tamarack Ranch

likely the old stage road

1865, Jan. 27

Lillian Springs Ranche was burned after 3 white men fought 500 Indians and then escaped.

Col. Robert R. Livingston (1st NE Cavalry) reports a skirmish [with Indians] at Lillian Springs Ranch on January 27, 1865

based on distance given by historical marker

Diagonal trace at bottom right is I-76

In staging overland, it was all-day and all-night riding over the rolling prairies, as it was across the plains and over the rugged mountain passes. But one would enjoy the long all-night rides far better when going along the Platte river, especially when there was a moon, which lighted up the surrounding country, its silvery rays being reflected in the waters of the beautiful stream, which silently flowed along the great overland pathway.

There were from eight to twelve animals kept at each station. At some of the stations it was necessary to keep a few head of extra stock, as occasionally an animal would be liable to get lame, sick, or be crippled, and at times unable to work; hence the necessity of a few extra head where they could be got without delay.

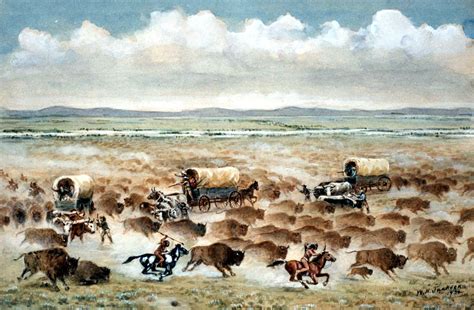

In the Platte valley were a great many deer, antelope, and an occasional elk, while a few miles distant, south from the stream and away from the heavily traveled thoroughfare, buffaloes abounded by hundreds of thousands. A great many came north to the Platte and there slaked their thirst. Buffalo-wallows were numerous along the Platte in staging days.

The native prairie wolves — the coyote — were quite numerous.

Dennisons Ranch

40.77357358010095, -102.9813433861555

1870 9N50WS07NENE labeled as Chicago Ranch

CO385 on trail at this point - east of Iliff - but heavy irrigation efforts have changed the road.

A CO Cavalry post at an Overland stage station located near the mouth of Cedar Creek

[Cedar Creek no longer shows on maps; perhaps absorbed by irrigation efforts]

1864, Late Dec.

Dennison's Ranche, barn, hay, and corral were burned by Indians. Horses were stolen from American Ranche.

1865, Jan. 10

Indians killed four men between Valley Station and Dennison's Station (U.S. Senate, 46th Cong., 2d Sess.). Captain O'Brien and the 7th Iowa Cavalry left the post to go to Camp Cottonwood [near Denver] to join General Mitchell on January 16 for a campaign near the Republican River. They went out after the Indians and returned January 30 after marching 500 mi and finding none.

The ranch provided fresh teams but was destroyed in the Indian uprising in January, 1865 and not replaced.

Washington Ranch

40.73110158148849, -103.07434689283588

9N51WS28NWSW

Washington Ranch stage station was operated by the Moore brothers. A detachment of the CO Cavalry was posted here in 1862. This ranch was also attacked by Indians in January 1865.

This ranch was founded by a former Pony Express rider, James Moore, and his brother Charles in 1861 or ‘62. There was a large store and huge corrals with very thick walls. The brothers and their employees successfully defended it against Indian attack on January 30, 1865.

Col. Robert R. Livingston (1st NE Cavalry) reports a skirmish at Charles Moore's Ranch (aka Washington Ranch) on January 26, 1865

I remember the Cheyennes were raising Cain along the overland stage route, attacking stages, plundering stations and mail-bags, and chopping down telegraph wires. This was in Colorado, between Fort Morgan and Fort Sedgwick. I went out with a company of sixty men to reestablish the route. We had just got beyond a place called Moore's, a sort of station for the stage line, and a stage came up as we laid in camp after a hard day's march. The Indians had been crawling around trying to surprise us; but no Indian fighter is ever surprised, and I was ready for them. The men on the stage were for going on; but I said : 'I wouldn't if I were you; for there's about sixty of those devils hiding among those sand-hills over yonder.'

The stage-driver knew his business and went back to Moore's. I told them I was going to march in the morning at five o'clock. There was a woman with her children in the stage, too, by the way. The men were indignant at turning back, but the driver had the advantage. Well, next morning about 7:30 o'clock we saw the stage-coach behind us in the sand-hills, and out popped the Indians. Part of us got back and drove them off. The Indian doesn't fight unless he has clearly the best of it from the start. Well, you ought to have seen the civilians who were so hot to go ahead the night before. They were shaking hands with everybody and crying and carrying on.

June 7 [1860]… Camped near an Indian village so we have plenty of company, begging & trying to sell moccasins. One squaw said she had dirt in her eyes and we gave her a wash dish and water and cloth. She washed herself and then her papoose and he cried loudly and it sounded more civilized than anything else we had heard. There was a very bashful young Indian who could not find courage enough to ask for anything so Mother filled a plate of victuals & he began to eat. When he had finished he strung his meat on a weed and got up. Another young one – a warrior – came up smiling enough and hands Edward his tomahawk, which served the purpose of pipe & so he points down into the bowl and said – smoke. He was quite intelligent and talkative, almost as soon as he came in an old Indian came in from the other fire, he shook hands – as they all do – and wanted to know if I was Mother’s papoose and Edward too, she told him yes, he pointed to the warrior and said HE was HIS papoose and talked quite loudly. The warrior took hold of the bashful ones tassel that hung around his neck on a breast plate of beads, and pointed to me and that plagued the bashful one considerably….

Preparing to make bread to bake in the morning, as we can’t have a fire tonight. We are camped about as far from another Indian village as we were last night so we expect company. We bake finally in Mrs. Wimple’s stove. Go to bed after preparing for rain, when we know it wouldn’t even sprinkle. Edward tells me of passing a grave Tue. On the headboard read – H. Wilson, Wis., 1859.

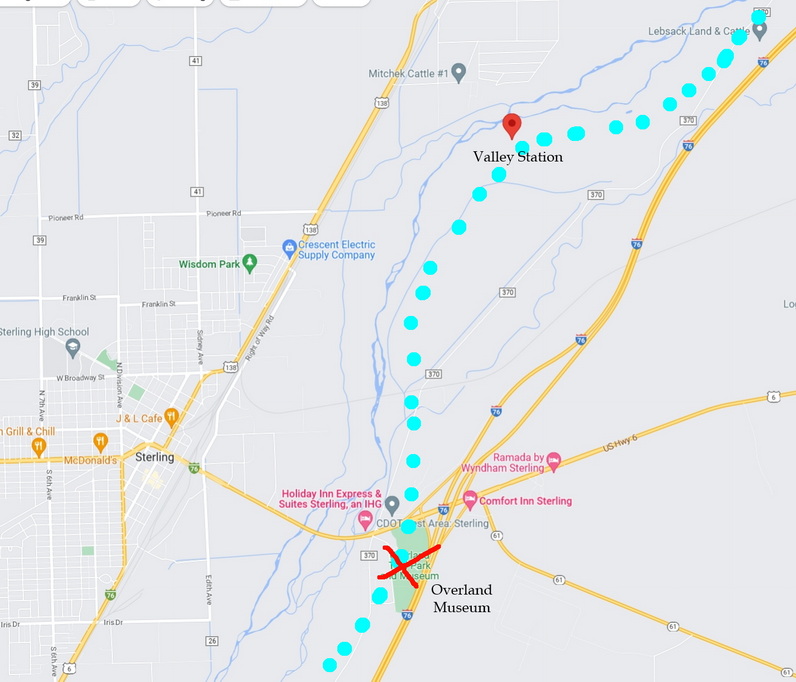

Valley Station

8N52WS13SW

40.660132928575514, -103.14121244048059

The Valley Station, near today's Sterling, was built in 1859 by the L&PP and was active throughout the life of the various stage companies. The station was sometimes referred to as Fort Moore, named for the operators of the station.

A telegraph office was built here in 1863 and served as the headquarters for the 3rd Colorado Company Volunteer Cavalry in 1864. During the Indian raids of January 1865, about $2000 worth of damage was done to the telegraph office and supplies but the station itself was spared as the soldiers used sacks of corn as a defensive structure. The soldiers were prepared; the Indians never attacked and retreated at sunset. When a company of cavalry arrived as reinforcements arrived, the station had been so severely damaged that "adobes" (bricks) were used to strengthen the defenses.

County Road 370 follows the trail here

George Bent, a half-white/half Cheyenne, participated in a raid with the Cheyenne near the Valley Station. The Cheyenne captured 500 cattle and had a skirmish with a company of army cavalry. The army claimed they killed 20 Indians and recovered the cattle; Bent said none were hurt, two soldiers were wounded, and only a few cattle were re-captured by the soldiers.

Col. John M. Chivington (1st CO Cavalry) reports a skirmish near Valley Station on October 10, 1864

Col. Thomas Moonlight (11th KS Cavalry) reports reports a skirmish at Valley Station on January 7, 1865

Col. Robert R. Livingston (1st NE Cavalry) and Lt. Judson J. Kennedy (1st CO Cavalry) reports a skirmish near Valley Station on January 15, 1865

Col. Robert R. Livingston (1st NE Cavalry), Lt. Judson J. Kennedy (1st CO Cavalry), Lt. Albert Walter (2nd CO Cavalry) reports a skirmish at Valley Station on January 28, 1865

Picture taken from I-76

To add to the annoyances in operating the line, scattered here and there over the plains and in the mountains were small bands of desperadoes from Texas, Arkansas, and other parts of the West, ostensibly hunting buffalo and other animals for their hides; but really it was plain that their object was to steal stock, rob the express coaches and passengers, and at times murder was resorted to in carrying out their hellish designs.

Sterling Overland Trail Museum

40.617810335882766, -103.18025912631857

8N52WS33/34

Located at Sterling exit of I-76

A railroad town, a post office was first established here in 1874.

Not a station or other significant place on the Overland Route, but located directly on the trail and a worthy stop for those interested in such things.

The stage road ran between I-76 and the river - through the museum site

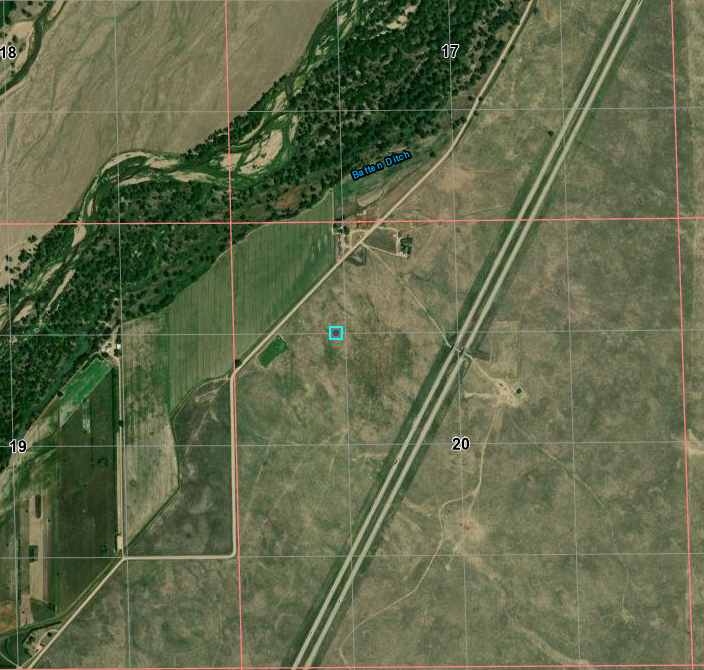

Wisconsin Ranch

7N52WS0NW

40.56310678353177, -103.21522166513049

Also referred to as Bull Ranch, this ranch was established by brothers Ralph and John Coad in 1862 as a supply station for their freighting business. A herd of oxen was kept here as well as storage for supplies to be taken to Denver during winter when prices were high. A third brother, Mark, was here with his sister, her husband, and their two children when Indians attacked in January, 1865.

Mark claimed that not only did he hold off the Indians but that he killed three of them. Soldiers later evacuated the family after the Indians had withdrawn. The ranch was nearly destroyed and it was abandoned.

Col. Robert R. Livingston (1st NE Cavalry) and Lt. Judson J. Kennedy (1st CO Cavalry) report a skirmish with Indians at Wisconsin Ranch on January 15, 1865

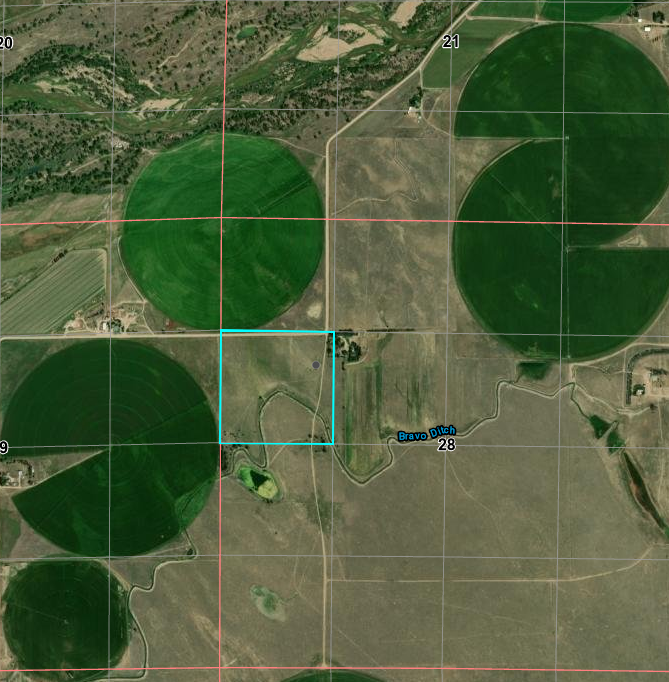

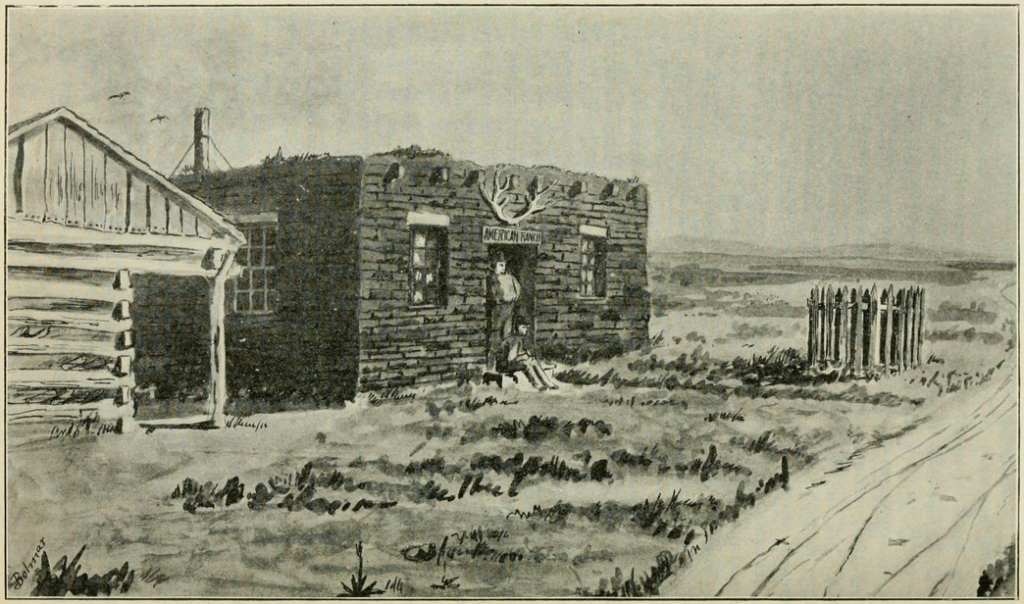

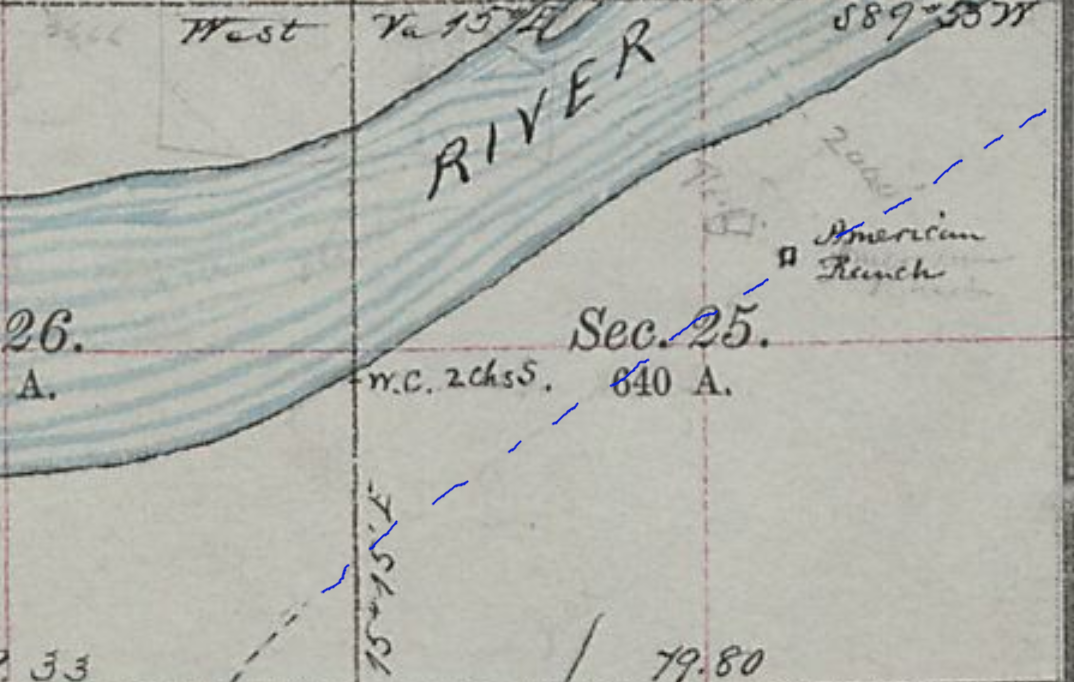

American Ranch

6N54WS25NESW

40.457887679548804, -103.35895269085525

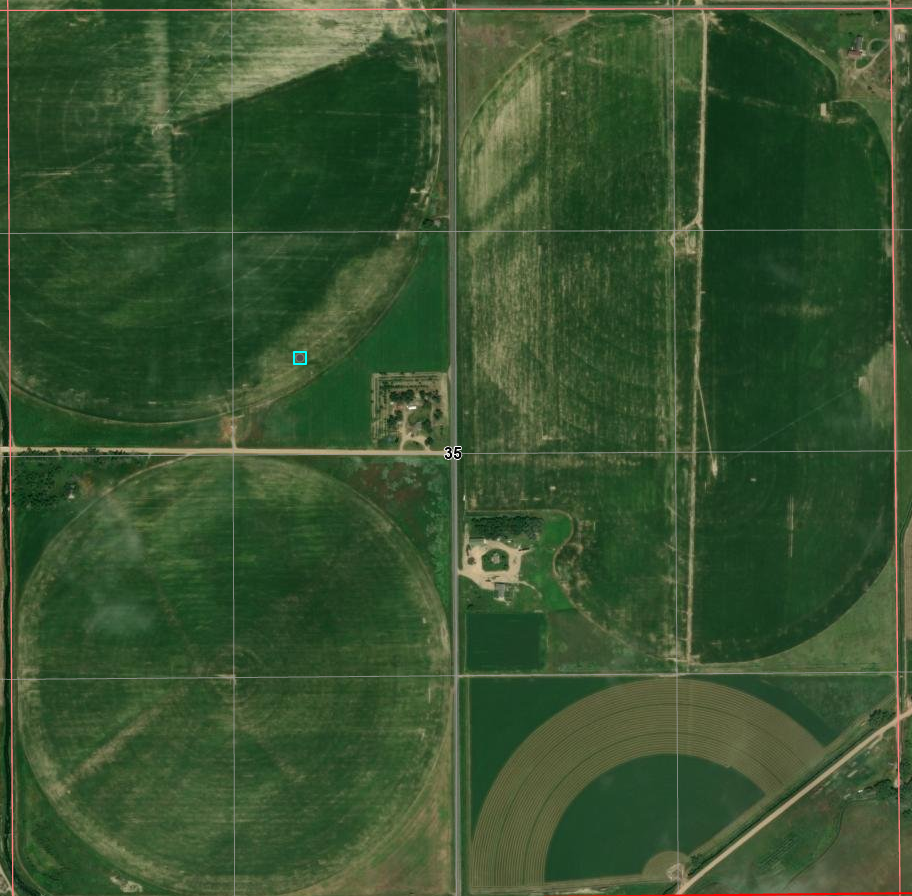

Just west of Road 55 within irrigation circle

Also known as Kellys Ranch - Kelly being the name of the operator, the station was located 15 miles from the Valley Station. The station became a post office in 1863. A swing station for changing teams, it was burned out in 1864 and suffered the loss 250 head of livestock. Kelly then abandoned it to the Morris family. During the Indian attacks in 1865, the Morris men were killed and the wife and children were taken. The wife survived; the children did not.

Col. Robert R. Livingston (1st NE Cavalry) and Lt. Judson J. Kennedy (1st CO Cavalry) report a skirmish with Indians at Morrison's Ranch

(aka American Ranch) on January 15, 1865

This faint trace appears to line up with the road in the 1872 map

1863:

After leaving American Ranch, about seven o'clock in the evening, we were caught in a severe snow- and wind-storm - a regular old-fashioned plains blizzard--and the night being dark we lost the road, and wandered about for four or five hours. The outlook was anything but encouraging. I was on the box with the driver facing the storm, but it was impossible to see ahead twice the length of the coach. Neither of us could tell where we were or in which direction the road lay, and everything indicated that we must stop there all night, and, perhaps, lose the team by freezing. But we managed a little before midnight, by the instinct of the faithful stage animals, and very much to our surprise, to pull up at Beaver Creek station.

The storm was still raging and, what seldom occurred on the overland line, we were obliged to lie up until morning. Many rough snow-storms have I encountered in Kansas, Nebraska, and on the plains, but was never caught in one more severe than this. We lay down on the floor at the station, rolled up in our blankets and robes for a few hours' sleep, got an early breakfast, and, with fresh team and a new driver, rolled out from Beaver Creek by daylight, the storm in the meantime having subsided. But it had left drifts like miniature mountains in many places, So that for the next sixty miles westward to my destination the team could not go out of a walk.

1865, Jan. 14

Beaver Creek Station was burned; Godfrey's Ranche was attacked but withstood the attack; Morris's American Ranche was burned and three men were killed, including William Morris. Mrs. Sarah Jane Morris and two children were captured by the Indians.

Godfreys Station/Ft Wicked - south of Merino

6N54WS35SE

40.44433160419779, -103.38195515543414

Even by 1873, the trail was called "The old Platte Wagon Road"

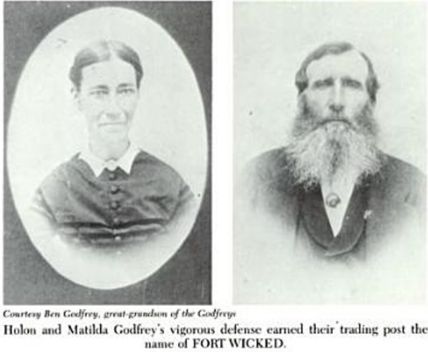

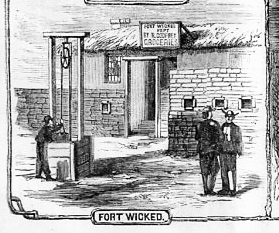

Not originally a stage station, the Godfreys operated a store here for travellers until 1867. It was known as Godfrey's Ranch until the Godfreys successfully defended the ranch against Indian attacks. Godfrey then gave it the name Ft Wicked. The site was abandoned after the railroads came, the sod buildings dissolved with the weather, and the trails were filled in or plowed under.

mid-section line is US6/I-76BR to Merino

1865

Frank Williams, a traitorous stage driver, was tracked to Godfrey's stage station and captured by the Montana Vigilantes, who returned him to Denver and hanged him.

Col. Robert R. Livingston (1st NE Cavalry) reports a skirmish with Indians at Godfrey's Ranch on January 14, 1865

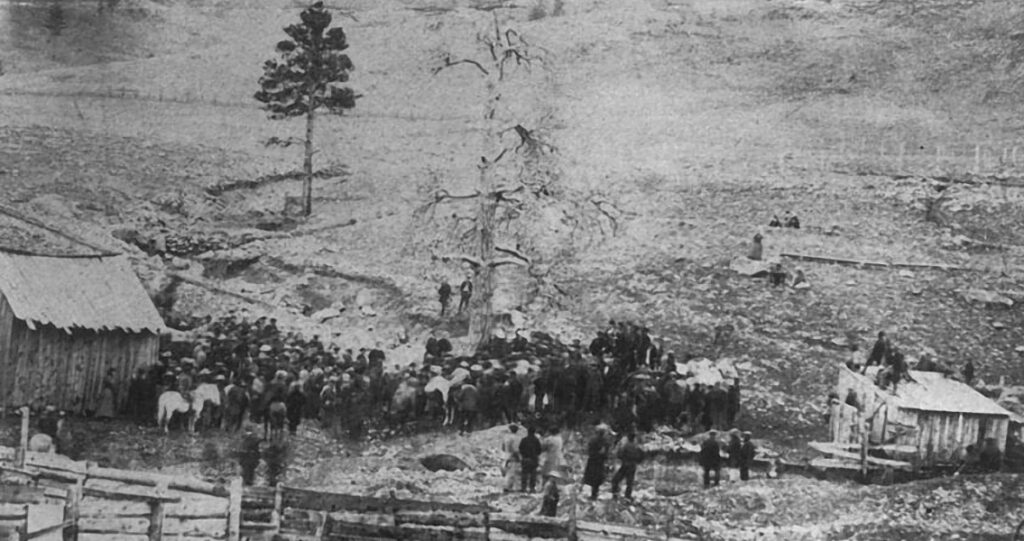

On January 14, 1865, about 130 mounted, painted warriors attacked Holon Godfrey's ranch on the east side of the South Platte, thirty miles northeast of Fort Morgan. Inside were the 52 year old Holon Godfrey, his 42 year old wife, Matilda, two of their daughters, 14 and 21, their six year old son, three month old daughter, and several men.

Holon was not unprepared. His ranch could be better characterized as a fortress, surrounded by six foot high adobe walls with one completed tower and one under construction, with port holes all around the compound. For two days, the Indians laid siege to the ranch, setting the surrounding prairie, the fodder for the animals, and the Godfrey's roofs on fire. They attacked with periodic sorties, raining arrows and bullets down on the defenders for the full two days.

When dawn broke on the 16th, the Indians were gone, leaving seventeen dead braves behind. There were no casualties in the compound. Holon Godfrey's resourcefulness and preparedness had saved his ranch, while many of his neighbors were being killed and driven off.

When Godfrey learned that the Indians had named him "Old Wicked" for his efforts during those two days, characteristically, he cackled and then nailed a sign up over the compound's entrance:

FORT WICKED

Kept by H. Godfrey

Grocery Store

Godfrey went on to be one of the largest cattle ranchers in the West. Matilda died in 1879, while Holon Godfrey died at the age of 88 in 1899. The ranch and Fort Wicked are long gone as well but there's a plaque and historical marker at the site of the ranch and battle on the side of Highway U.S. 6 about three miles southwest of Merino, Colorado.

“…We saw a great many Indians and passed a great many villages, some large ones. At first they were Sioux and then Cheyennes, the Arapaho Indians occupying the territory immediately east from the mountains. Of the three tribes, the Sioux were much the most numerous; but all three tribes had been friendly for generations and their language was very similar. The end of that week, Sunday 27th, found us camped on the south bank of the South Platte, a little east of Beaver Creek, and about five hundred miles from Nebraska city…. At this point we began to meet some returning pilgrims, with tales of disaster and impending attack from the Indians; the latter rumor did not disturb us because the presence in all the Indian villages of the usual number of squaws and papooses was a sign of no immediate trouble….

Beaver Creek

4N55WS08NENE

40.3326493253768, -103.54859972142586

This is about 12 miles from Kellys and 19 miles from Bijou

1864, July 2

Indians killed two emigrants on the stage road near Beaver Creek. Later in the month ·they killed two more near Junction Station.

Beaver Creek was another 12 miles beyond American Ranch. Diaries of the west-bound travelers noted this as the place they would get their first view of the Rockies.

The station itself was built in 1864 and consisted of two log structures having two rooms each. Until burned out by Indians in January of 1865, this was a home station with meals available.

The actual location is unknown - the station is marked as at the proper distance and at a water source.

While coming east along the Platte, early one evening during the summer of 1863, a rather singular accident befell us, while we were bowling along at the usual gait. Just after sunset the off front wheel of the stage — the one directly under the driver's seat — ran off the axle. Before any one on the coach had time to even think, there was an exciting runaway. The team was full of life, and in its wild dash down the valley it seemed that it sped with almost the rapidity of a fast-mail train. I expected every minute to see the driver tumble headlong off the box ; so held on to him as best I could with one hand, saving myself with the other. With my assistance he managed to keep his seat. For 200 or 300 yards or more the four horses fairly flew ; they went so fast that the axle was kept from dragging on the ground. Finally the driver, by application of the brake, succeeded in bringing the team to a halt.

Climbing down from the box, I ran back to find the wheel and the missing nut. I knew when the wheel rolled off and where it should be found, but it was some time ere I succeeded in finding the nut, which was accomplished by the aid of one of the coach lamps and a careful search. Inside the stage were five or six frightened passengers, but they all had to alight and help lift to enable us to get the wheel in place, so as to proceed on our journey.

Junction Stations ...

Plural as there were several "Junction Stations" - perhaps as many as five - set in this area near present-day Ft Morgan area as different paths heading SW to Denver were developed. Upstream - west-bound - from this area, the river swung NE for many miles before swinging SE again. A cut-off from this region shortened the distance to Denver and avoided a bad stretch of trail between Bijou Station and Freemonts Orchard ... but had its own problems as well.

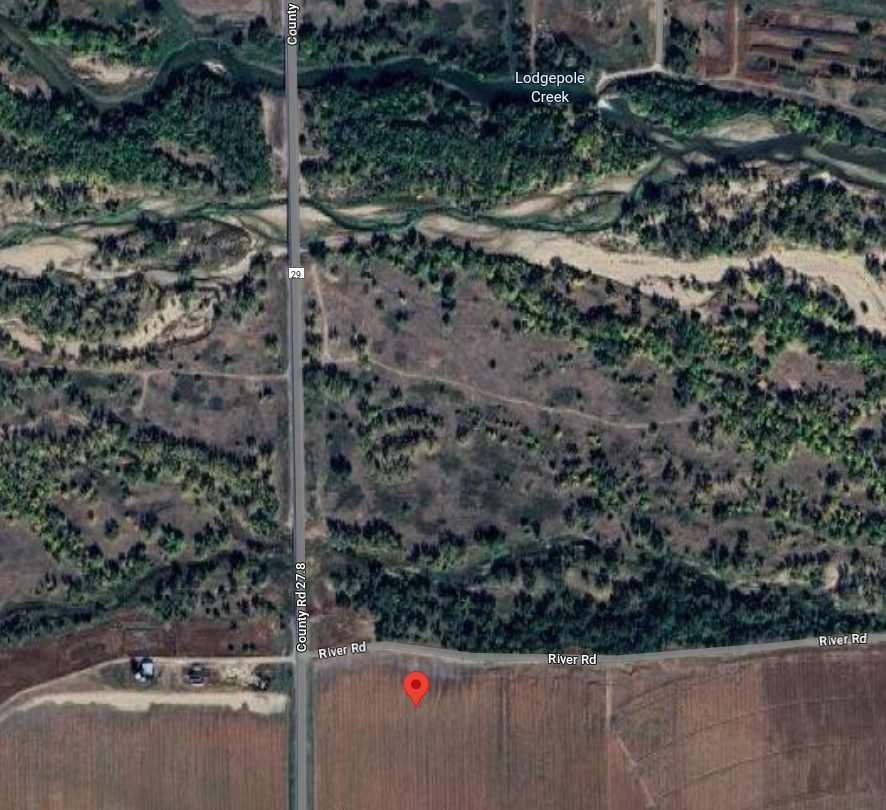

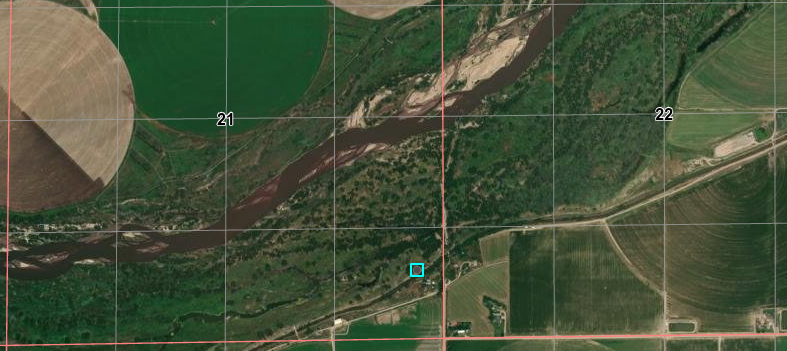

Locating these junction stations has proven difficult; most surveys of the area were completed after the Overland/Wells-Fargo lines no longer ran and the area showed significant development in the five years between 1869 and 1874 as the danger of Indian attacks had lessened considerably and ranches were developed along the bottom-lands of the river.

The first and main cut-off was established at Ft Morgan - or Ft Tyler at the time. It was constructed in 1864, about 18 miles upriver from Beaver Creek. A swing station named Junction was established and a company of Colorado cavalry was stationed here during the time of Indian raids. However, several other "Junction Stations" were established in the region.

Setting a discussion of Ft Morgan aside for now, there were two other possible locations fitting the descriptions:

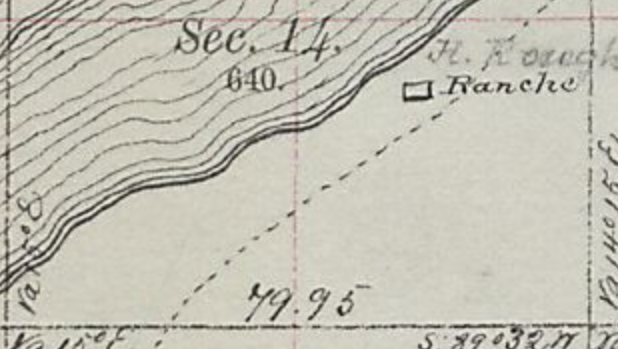

The 1871 map shows the trail passing by the "H. Ro(ce)gh Ranche". The map does not indicate a junction at this point - but then, many of the survey maps neglected to place the trail or the tracings have faded over the years.

4N56WS14SENW

40.3109844975356, -103.60812792250832

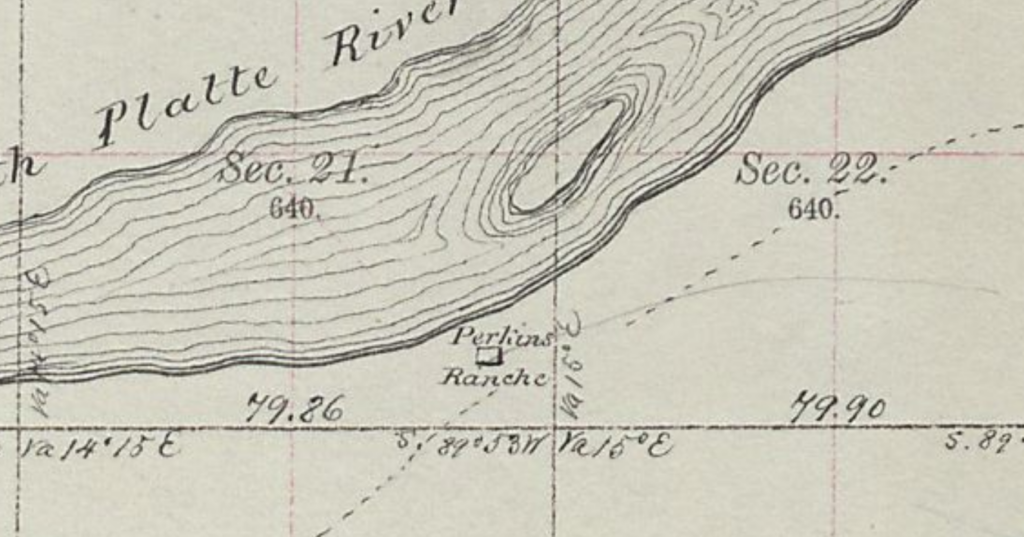

Some records suggest a location for "Junction Station" at what later became Perkins Ranch. So named as the trail split here; one branch heading SW to Denver, the main branch continuing along the river; there were at least five stations known as "Junction" so pin=pointing any one as the "Junction Station" is difficult.

4N56WS21SESE

40.29287111578254, -103.64187804338914

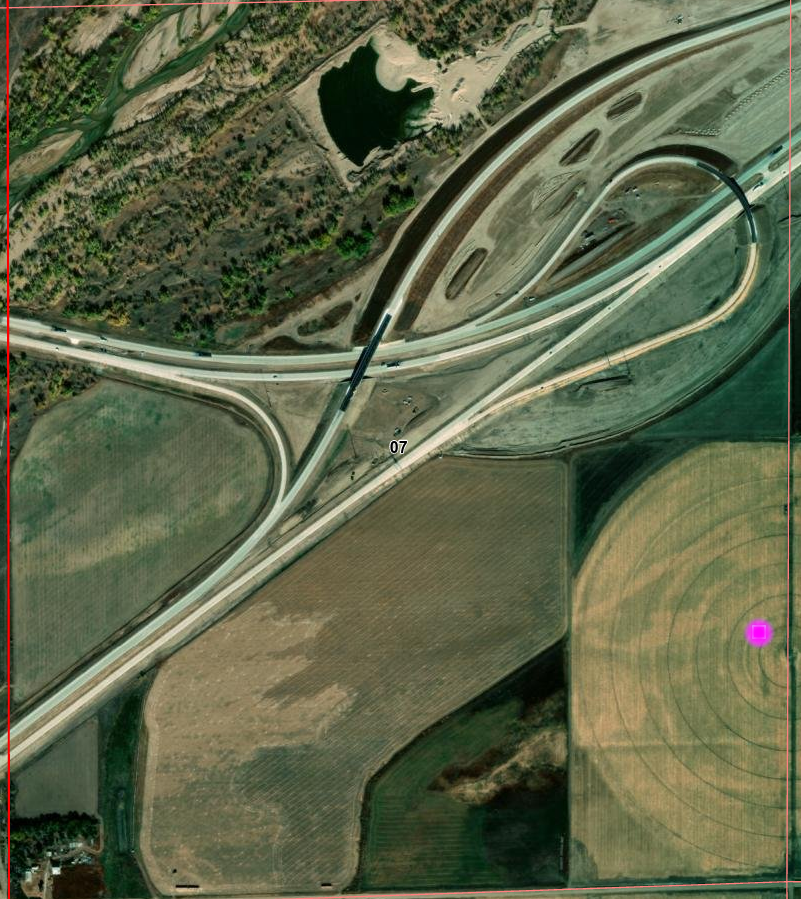

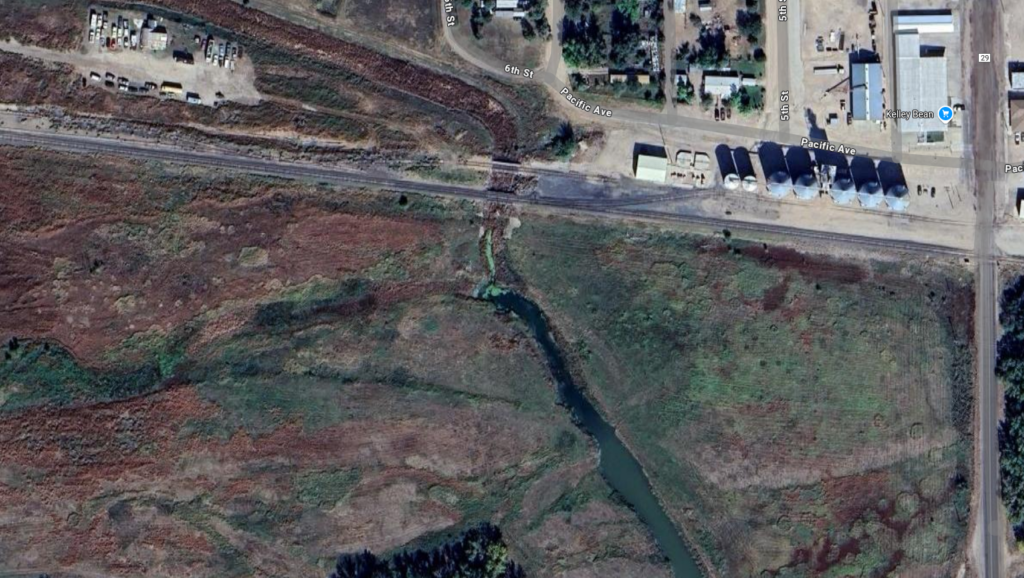

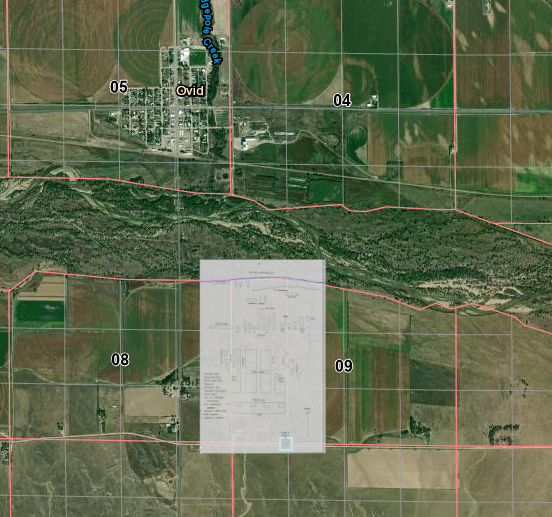

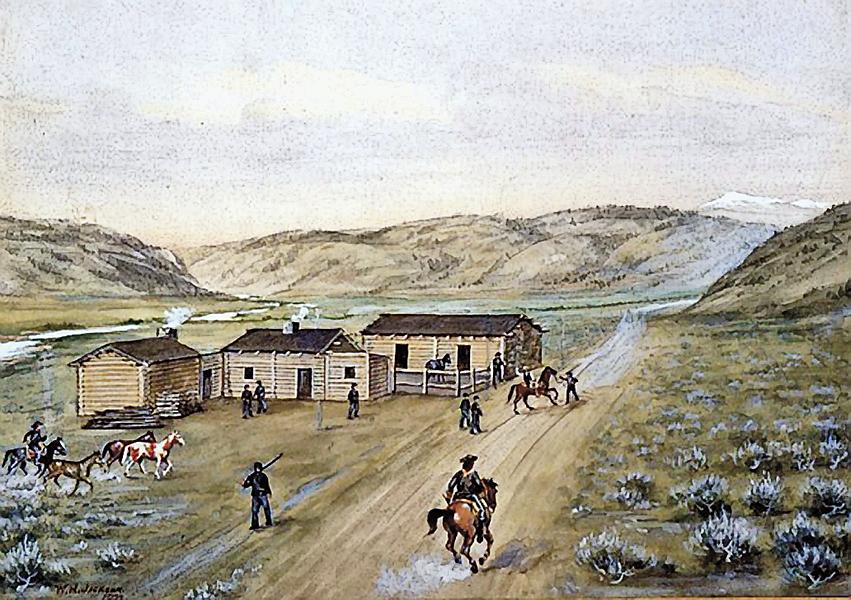

Junction Station/Fort Morgan

4N57WS31SWNE

40.86122036083934, -105.25623029154512

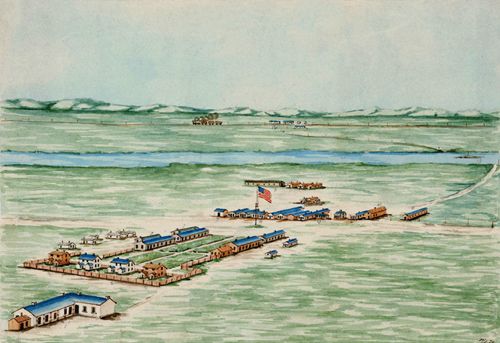

A fur trading post was established in this area in 1838 by a Sam Ashcroft. Later, the site was selected for Camp Tyler, built in 1859 three miles east of the mouth of Bijou Creek along the safest route to the Pikes Peak diggings. It was constructed of log-reinforced sod, located near an Indian crossing of the South Platte River, and used to guard the stage line and nearby ranches. The fort supported a detachment of 150 cavalry troops of galvanized Yankees, later by infantry. The camp was named for a volunteer military unit from Central City. In 1865 the name Camp Tyler was changed to Fort Wardwell, then on July 14, 1865. to Camp Wardwell. A year later, the camp was renamed Fort Morgan. The site of the fort is right on the south bank of the South Platte at the Junction Ranche, the site of the trading post.

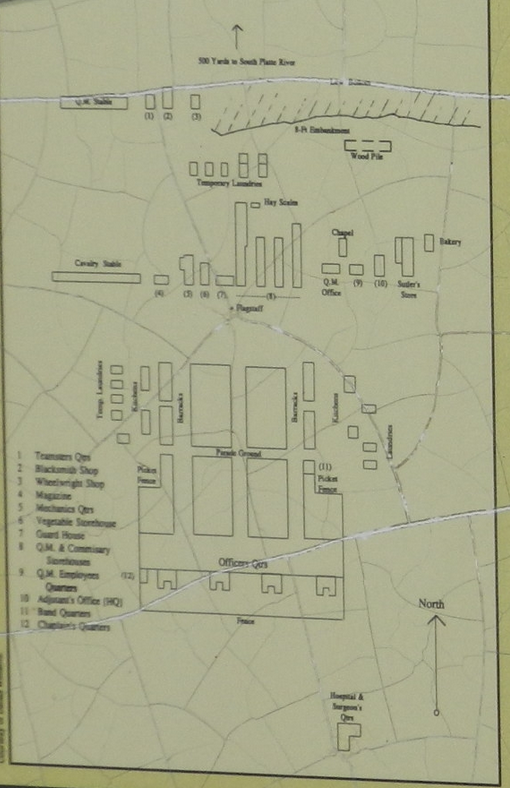

The fort had officer's quarters, servant's quarters, lookout towers, flag tower, magazines, close guard houses; long mess rooms, bunk houses, stables, and raised rooms on the southwest and northeast corners of a stockade, each with a 3-inch Parrott gun. The last company stationed at Fort Morgan was of infantry in September 1867. The fort was abandoned in May, 1868 when the railroad reached Denver and the post no longer needed. The remaining detachment was moved to Fort Laramie in Wyoming.

The cutoff was established in October 1864 by Ben Holladay to save about 40 miles and three days travel to Denver as well as attempting to avoid a rough stretch of road and Indian attacks further up the South Platte. By December the military officials had ordered Holladay to officially adopt this cutoff, bypassing the stage stations between Fort Morgan and Latham, and the post was temporarily named Post Junction. The cut-off was built along a wagon trail which had been used by freighters as early as 1860. Even though water and good grazing were not as plentiful as along the South Platte, Holladay felt that the savings in time was well worth it. Post Junction Station was built as a home station when the cut-off became active. As a home station, it provide storage for supplies and held a telegraph office. The far to Denver was $3.90.

The town of Ft Morgan wasn't established until 1884. Nothing remains of the original fort but a marker in a city park. The city proper lies south of present day I-76 while the stage station was slightly north of the expressway. The Ft Morgan exit off I-70 lies on the former fort grounds

Both of the older maps post-date the active Overland operation but the trails would still be used for local stage lines and freight. The 1869 map unfortunately doesn't show the trail but the 1874 map which fits directly below the upper map shows what appear to be the cut-off trails. Since the cut-off was established in 1864, it is assumed the earlier trail passed through Ft Tyler as it was known at that time and continued along the South Platte to Bijou Station, only a few miles upriver from Ft Tyler.

Get fairly early start. Rough is quite well, and if there is no alkali in the soft ground the cattle will do very well. Find some beautiful flowers. See 8 cattle and 2 horses that have died lately, before 1 o’clock. Went to a grave and it had on it G. H. Hopkins – died June 7th, 1860 from Deboque [sic], Iowa. We passed the cut off soon after. We find some sand hills but keep on up the platte as we have been advised to do. We have crossed two alkali sloughs and are now within 7 miles of Fremont Orchard. We camp tonight across an alkali slough where two of the company’s wagons and two others get stuck, they get out after a long time and by that time the wind begins to blow….

There are no modern roads which follow the trail between Ft Morgan and just west of modern Orchard

A Slight Detour - Touching the cut-off trail a bit south to Denver

Examining a bit of the cut-off route to Denver ...

There is some dispute over exactly where some of the stops or stations were located along this cutoff. The Tegler Ranch, located about 14 miles to the southwest from Fort Morgan may have been a station. It definitely was a spot where the coaches could stop.

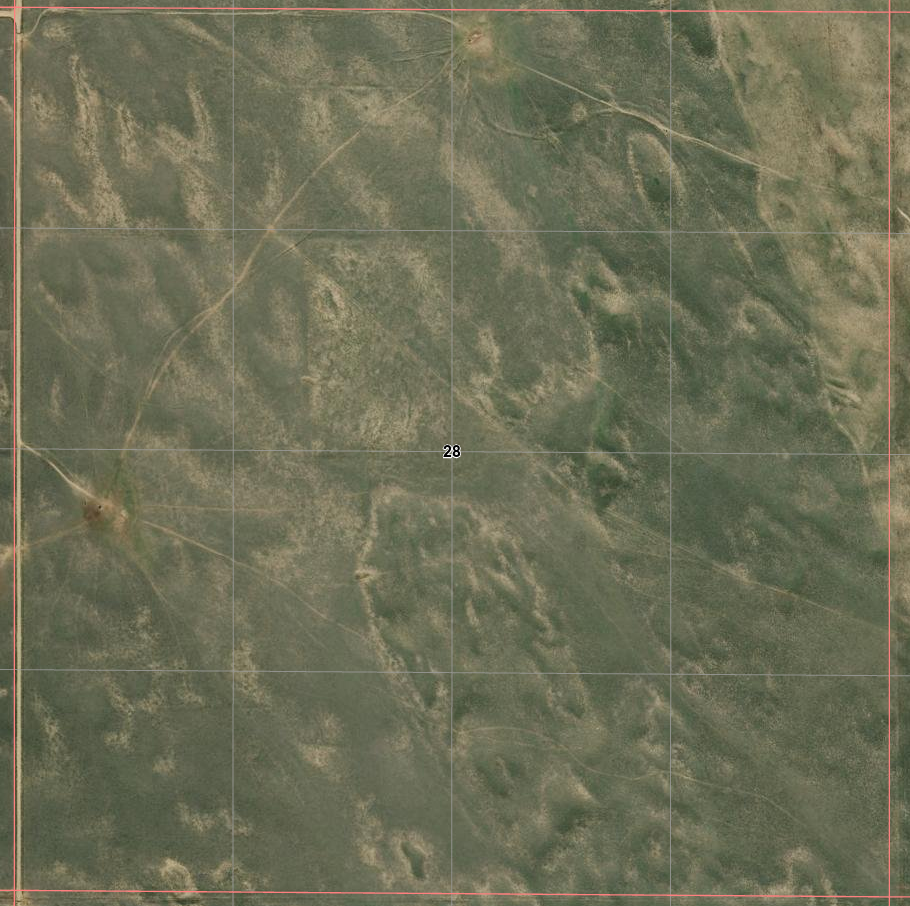

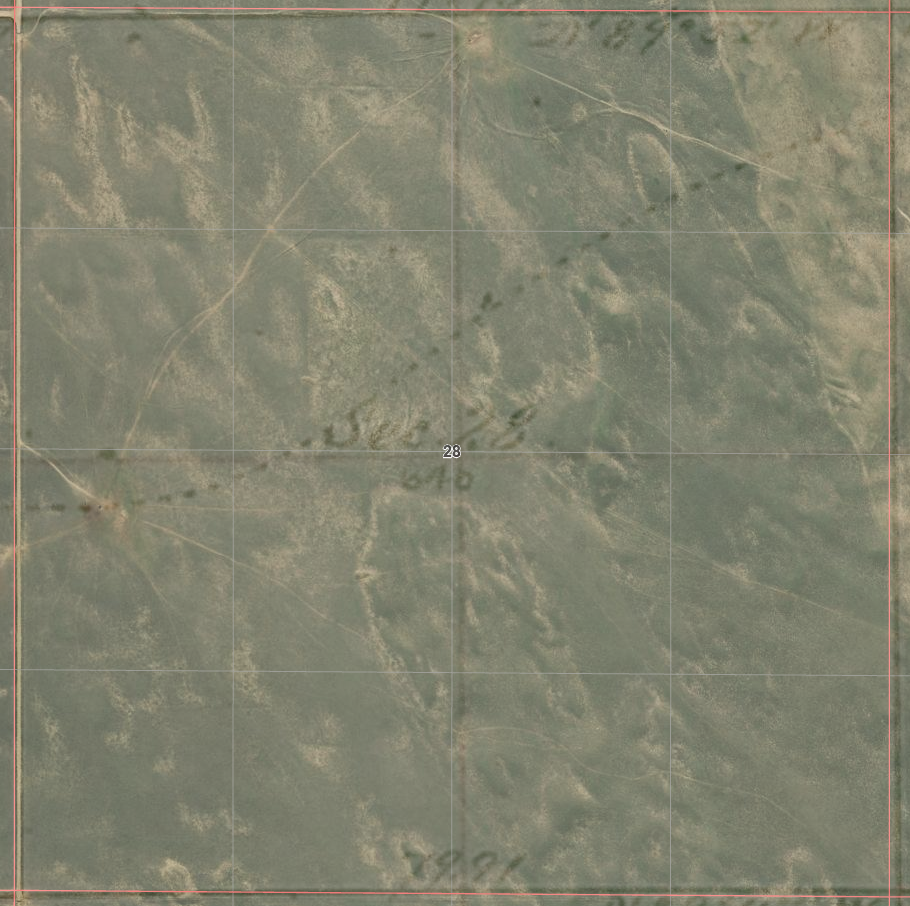

These map sections show a location roughly 14 miles along the cut=off trail. No ranch is indicated on the older map - which is not surprising - and the site of the stage road today is now irrigated cropland.

A little further on along the cut-off trail, a section that once contained a trail of heavy traffic now shows no sign of the trail

40.19533814445095, -103.98022020324836

Looking across this location - public access not allowed - probably doesn't look too different than it did in the 1860s

Two other ranches, located about one mile apart, the Allred and the Graham Ranches, may also have been the site of a station. These are about 15 miles south of the Tegler Ranch. There is an old building on the Graham Ranch which local tradition claims to have been an Overland Station, and where Indian raids and stage holdups took place.

There was a point where the cutoff divided into the "new" cutoff and the "old" cutoff. Since this section of the trail went over an area of sand dunes, the two routes paralleled each other for 20 miles or so. A station was built right at the base of the bluffs along Rock Creek on the "new" cutoff. This entire section of the trail went over an area of sand dunes. It is possible that the "new" cutoff was just avoiding difficult terrain.

ON Monday morning last, Mr. Beard and I took our seats in the overland coach, at Denver. Our hopes of a comfortable trip were blasted at the outset: there were seven passengers for Fort Kearney, and four for the “Junction,” [Fort Morgan] as it is called, on the Platte. The fare of one hundred and twenty-five dollars which one pays the Holladay Company, is simply for transportation: it includes neither space nor convenience, much less comfort. The coaches are built on the presumption that the American people are lean and of diminutive stature — a mistake at which we should wonder the more, were it not that many of our railroad companies suffer under the same delusion. With a fiery sky overhead, clouds of fine dust rising from beneath, and a prospect of buffalo-gnats and mosquitoes awaiting us, we turned our faces toward “America” in no very cheerful mood. The adieus to kind friends were spoken, the mail-bags and way-bill were delivered to the coachman, the whip cracked as a sign that our journey of six hundred miles had commenced, and our six horses soon whirled us past the last house of Denver….

Toward evening the clouds lifted for an hour or two, and we took our last look at the Mountains, lying dark and low on the horizon. The passengers for the Junction were pleasant fellows, and I mean no disrespect in saying that their room was better than their company. After sunset another setting in of rain drove them upon us, and by eleven at night (when we reached their destination) we were all so cramped and benumbed, that I found myself wondering which of the legs under my eyes were going to get out of the coach. I took it for granted that the nearest pair that remained belonged to myself…. The coach is so ingeniously constructed that there are no corners to receive one's head. There is, it is true, an illusive semblance of a corner; if you trust yourself to it, you are likely to lean out with your arm on the hind wheel. Nodding, shifting of tortured joints, and an occasional groan, made up the night. There was no moon, and nothing was visible except the dark circle of the Plains against the sky.

Tuesday night, the 29th, [May 1860] we camped on the bank of the Platte where the new trail called “The Cut Off” leaves the round-about river trail and strikes straight across to Denver. We understood that as our teams were in such good condition it was possible for us to go through in two good days travel. The only real trouble was said to be the very poor water and a great scarcity of it. But it was finally decided to take “The Cut Off” trail, although it was also said to be a very sandy heavy track. So Wednesday morning, May 30th, after having filled every keg, canteen, or other utensil in which a little of the Platte River water could be carried, we left the river behind us and hit the new trail for Denver. That night we camped near a stage station where we could get water for the teams. Thursday we traveled on through a region apparently made up of sand, cactus, and Prairie Dog towns, and at night camped on Kiowa Creek, a little very brackish water along in pools. Friday morning we drank the last of the Platte River water and hit the trail early, expecting to be in Denver before night. The next water was said to be a little shallow pond of surface water about half way between Kiowa Creek and Denver. It proved to be a very hot day and before noon we began to suffer for water. About noon we came to the place where the pond had been, but there was no water, just a small area of damp soft mud, all tracked up by the feet of men and of animals, wild and domestic. We tried digging for water but got none. Gave the teams some grain but they ate very little. We ate what we could of some cold corn bread and raw side meat, then started on.

At sundown with Denver still at an unknown distance, we stopped to rest and feed the teams, but they would not eat; neither could we. Things began to look very serious much of the trail was very sandy, and the loads cut deep and dragged heavily. Fortunately the moon was at the full, sailing high in a cloudless sky, and as night came on the air got cooler. We started on again, hoping as we came to the top of each roll in the prairie, to see the lights of Denver below us. I shall never forget the hours that followed as we toiled on in the moonlight, with frequent stops to rest the exhausted teams, and then with whip and voice urging them to drag along the heavy loads. My thirst was also becoming unbearable – torturing. At last, somewhere near midnight as we came up on a little rise of ground and stopped for a moment, our mules cocked their ears forward and began to he-haw – he-haw most vigorously. I think that was one of the sweetest strains of music that I ever heard, for it told us that the mules smelt water ahead. We had no more trouble urging them forward. A mile or so farther and from a little rise in the prairie, we looked down on a host of twinkling lights that said Denver lay before us .”

2N59WS17NWNW

40.144905395867156, -104.01690168833207

But this line of exploration leads down yet another rabbit hole ... and this isn't the route we travel; we're not heading to Denver ...

Next: A return to our journey to Echo Canyon: Junction to Latham

Continue reading →